Mexico: Surge in numbers of survivors of extreme violence, mental health consultations at Mexico City centre

Insecurity in Mexico and on the Central American migration route, as well as new restrictive U.S. immigration policies, among main factors

The number of mental health consultations and new patients admitted to the Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) Comprehensive Care Centre (Centro de Atención Integral or CAI, in Spanish) for survivors of extreme violence, based in Mexico City has increased significantly in the last six months.

MSF attributes the increase to continued violence at the hands of various armed groups – both organized crime groups and security forces – along the migration route through Central America and Mexico, fuelled by a slew of harsh changes to immigration policies by the U.S. and other governments in the region. As needs increase, MSF urges public entities and non-governmental organizations to strengthen assistance to people in Mexico who have been victims of violence and are seeking safety.

In the first quarter of 2025, MSF teams provided 485 individual mental health sessions to patients at the CAI – migrants in transit through or stranded in Mexico and Mexican citizens. This represents a 36 per cent increase compared with the number of sessions provided in the three months prior. Throughout 2024, MSF provided an average of 300 to 350 individual mental health sessions each quarter. Between January and March this year, the most common conditions people presented with were post-traumatic stress disorder (48 per cent) and depression (39 per cent), as well as acute stress reactions (seven per cent), grief and anxiety.

The impact of restrictive U.S. immigration policies

“Since the end of January, we have treated people with severe mental health issues due in large part to the impact of restrictive immigration policies recently implemented by the U.S. and other governments in the region,” says Joaquim Guinart, coordinator of the CAI.

A flurry of executive actions taken by the U.S. administration in January included the declaration of a national emergency at the U.S. southern border – effectively militarizing immigration enforcement – and the temporary suspension of refugee admissions to the U.S.

“These abrupt changes have left many people trapped in legal limbo, with no pathway to seek asylum and no access to essential services or protection.”

Joaquim Guinart, coordinator of the CAI

Even before the executive orders were issued, the new American administration took swift action to shut down the CBP One app that, despite its flaws, was the only way to apply for asylum at the U.S. southern border. The impact of these restrictions is further compounded by funding cuts to humanitarian programs, severely affecting access to shelter and basic healthcare needs.

“These abrupt changes have left many people trapped in legal limbo, with no pathway to seek asylum and no access to essential services or protection,” says Guinart.

These combined measures further erode access to asylum and increase the risks for migrants – particularly children and other at-risk groups – as people are pushed towards using increasingly dangerous routes and methods to seek asylum or trapped in unsafe locations where they are at heightened risk of kidnappings, extortion and sexual violence.

Helping patients recover with comprehensive care

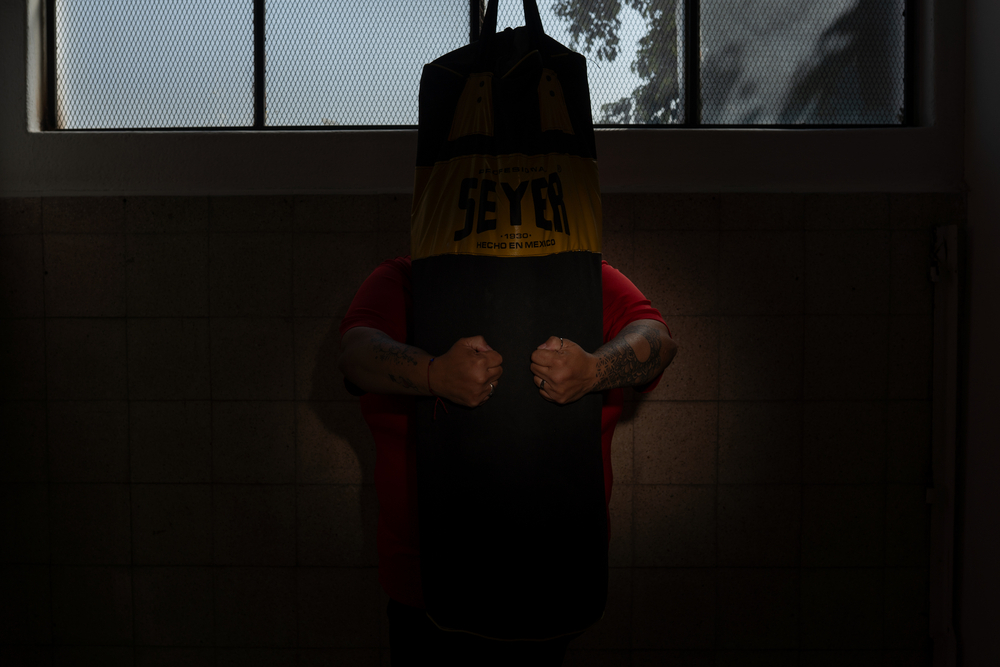

The CAI opened in 2016 to provide comprehensive care for survivors of extreme violence and torture, including medical care, psychology sessions and physical therapy, among other services.

The goal is to help patients regain their autonomy and heal physically and emotionally. Most people receive three to six months of treatment, and there are between 30 and 50 people admitted at any one time. In 2024, MSF teams identified 4,500 survivors of moderate to extreme violence through our projects in different points of attention in Mexico or through partners. We admitted 186 to the CAI for comprehensive treatment, others were provided care through mobile and fixed clinics or referred to other organizations for care.

Although most patients admitted are migrants, since the last quarter of 2024, the CAI has also focused on treating Mexican patients who are displaced or affected by violence occurring in various parts of the country. This coincides with a significant increase in admissions to the CAI during that period – 64 in total, which represents an increase of more than 50 per cent over the usual quarterly average of 40.

“Violence leaves deep scars, not only causing physical damage, but also serious psychological disorders. Specialized care is required as many patients experience changes in their perception of safety, trust and wellbeing.”

Joaquim Guinart, coordinator of the CAI

“The goal is for patients to regain their functionality and reintegrate into society,” says Guinart. “The CAI is a refuge for those affected by violence. Kidnappings, extortion, abuse, sexual violence and other forms of violence affect many people along the migratory route from the south of the continent to Mexico’s northern border with the United States.”

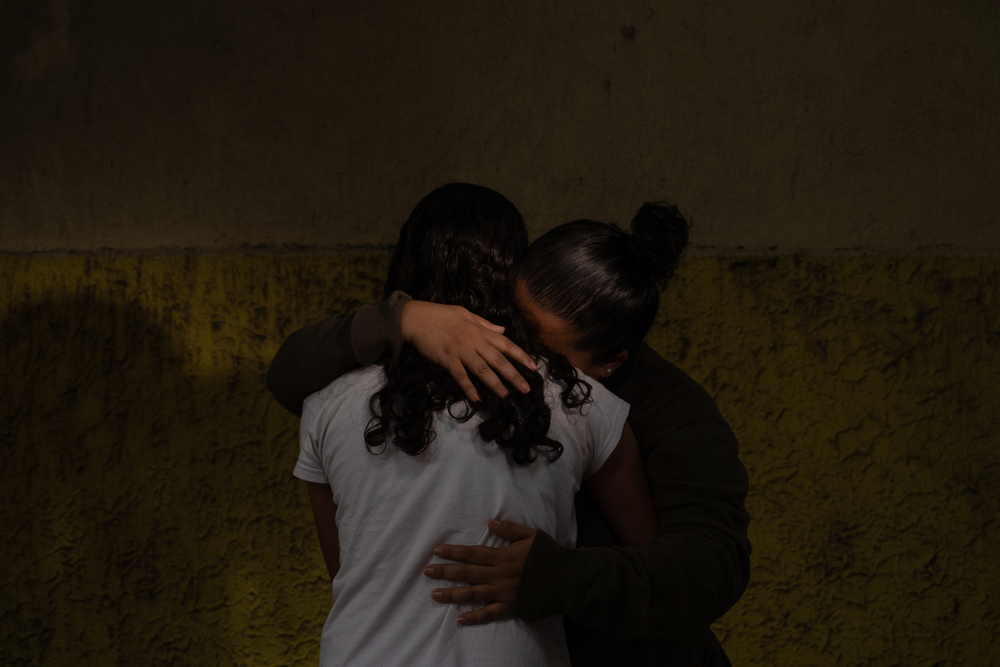

“At the CAI we find people in extreme situations of vulnerability,” says Guinart. “Women and children make up the bulk of the cohort. We also care for many LGBTQI+ people. Violence leaves deep scars, not only causing physical damage, but also serious psychological disorders. Specialized care is required as many patients experience changes in their perception of safety, trust and wellbeing.”

“I didn’t know if I would be able to trust people again,” says Elena*, a patient at the CAI. “The violence made me feel unworthy of love or respect.” Through therapy, Elena has begun to regain her self-esteem. “I’ve learned that my past doesn’t define me and that I can build a better future.”

“Every day is a struggle,” says another patient. “Anxiety consumes me, but here I feel I have a safe space to express myself and heal.”

“The difficulty in accessing adequate care makes recovery for many people affected by extreme violence much more arduous,” says Henry Rodríguez, MSF general coordinator in Mexico. “In these challenging times of cuts in humanitarian assistance, it is essential to recognize the importance of providing comprehensive support and cooperation between public entities and non-governmental organizations to direct people to the few services available.”

*Name has been changed.

Our work in Mexico and Central America

Between January 2024 and February 2025, MSF teams in Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, Costa Rica and Panama treated nearly 3,000 survivors of sexual violence and provided more than 20,000 individual mental health consultations, many of them precipitated by violence, displacement and difficulties in the migration process.