Bangladesh: MSF significantly expands hepatitis C programs in Rohingya refugee camps

MSF aims to treat 30,000 people with hepatitis C, amid critical lack of treatment options

Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) teams are seeing concerningly high levels of hepatitis C in Rohingya refugee camps in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh. We are significantly expanding out treatment programs in response and aim to treat 30,000 people with hepatitis C by the end of 2026.

The initiative will improve access to care for Rohingya, a stateless people who are particularly exposed to this curable, but potentially fatal, disease. MSF is now establishing three specialized treatment centres within existing health facilities as part of a “test and treat” campaign, which seeks to reach around one third of all people living with hepatitis C in the camps. This “test and treat” strategy will ensure that people who test positive for the virus are put on treatment quickly, improving their health and curbing further spread of the virus in the camps.

Between October 2020 and December 2024, MSF treated over 10,000 people for hepatitis C at our clinics in Jamtoli camp and at the “hospital on the hill.” However, a 2023 MSF study published last month in The Lancet Gastroenterology and Hepatology found that nearly one in five adults – an estimated 86,000 people – are living with chronic active infection, highlighting the critical need for a more robust response.

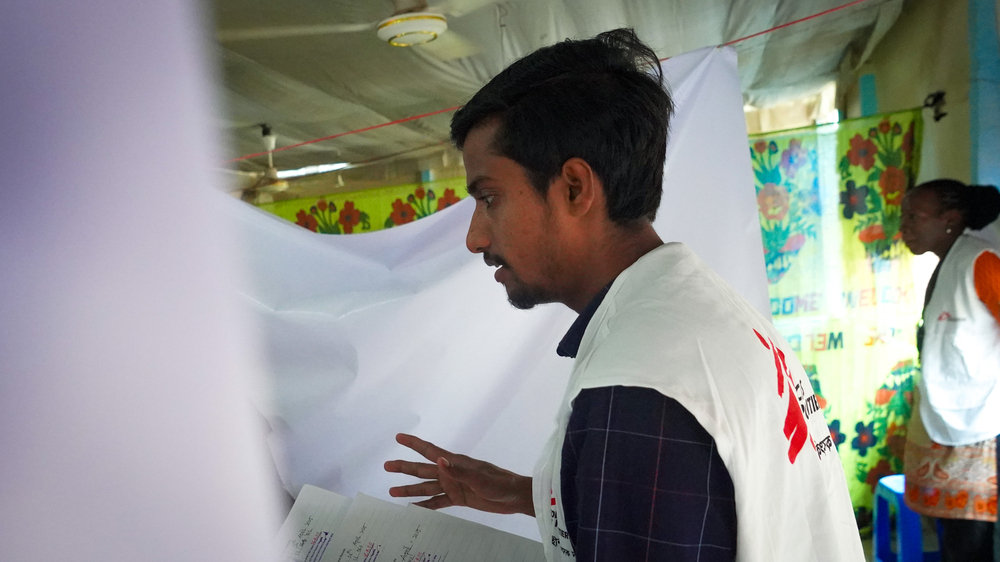

“Access to hepatitis C care in camps, where more than a million refugees have been living for the past eight years, has been extremely limited,” says . Wasim Firuz, doctor and MSF deputy medical coordinator. “Treating hepatitis C is not part of the package of healthcare provided by overstretched healthcare facilities. People are also not allowed to freely leave the camps to access healthcare and even if they could, it’s unlikely they would be able to afford the cost of treatment.”

In Bangladesh and neighbouring Myanmar, several factors increase the risk of infections – including hepatitis C – among Rohingya communities. Living conditions are harsh in the cramped and overcrowded camps, people lack access to healthcare and a lack legal status severely restricts people’s basic rights. MSF’s survey found that exposure to unsafe medical practices over decades, such as therapeutic injections, could be the main reason for the transmission of this blood-borne disease within the camps.

As part of MSF’s scaled-up response, our teams are conducting systematic community-based screening to proactively identify people with hepatitis C, a disease that does not show any signs or symptoms in its first phase. Rapid testing is followed by laboratory confirmation at the newly established treatment centres in Balukhali and Jamtoli camps and at “hospital on the hill.” MSF is also running a comprehensive healthcare awareness campaign. This includes providing drugs for hepatitis C treatment and sharing prevention messages and treatment adherence counselling to adults.

“While we are scaling up efforts and working in coordination with other organizations, the limitations within the health response, including insufficient staffing, equipment and resources among partners, present a significant obstacle.”

Wasim Firuz, MSF deputy medical coordinator

“In the absence of other alternatives to hepatitis C care for tens of thousands of people in the camps, we are undertaking this substantial increase in our treatment capacity,” says Firuz. “This expansion represents a vital step towards preventing the spread of hepatitis C, especially to younger generations.”

Addressing this widespread hepatitis C epidemic nonetheless presents considerable challenges within the limited capacity of the overall health response in the camps. MSF will be conducting research to analyze such challenges and bring about solutions as part of our response.

“While we are scaling up efforts and working in coordination with other organizations, the limitations within the health response, including insufficient staffing, equipment and resources among partners, present a significant obstacle,” says Firuz. “Our campaign is temporary and will not eradicate hepatitis C in the camps. Attention to hepatitis C must continue during and after the end of this campaign. We again call on other health partners and the international community to prioritize building a comprehensive strategy, to reduce the devastating impact of this disease on this community.”