Myanmar: MSF’s Yangon office becomes clinic amid collapsing health system

The violence and intimidation committed by security forces in Myanmar is creating a climate of fear and disrupting HIV patients’ access to life-saving antiretroviral treatment.

Ko Tin Maung Shwe is a high-risk patient who has both HIV and hepatitis C. He needs regular consultations to monitor his condition and medication to control the symptoms, but this has become increasingly difficult since the military seized control of the country on February 1.

“Today’s journey is not as easy as it was. I didn’t have to worry about anything before. But now, I need to be careful about even going around the corner because soldiers check cars, phones and people. That’s why I am scared. I have to make calls before I leave to find out how the routes are. Then I go out if things seem fine,” said Ko Tin.

Medication is essential

“If I did not make it to the places where the medication is provided, I would not be able to take them and I would die. This medication is vital for me to live.”

Ko Tin lives in Thaketa Township in Myanmar’s commercial capital Yangon where he usually visits a clinic staffed by Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) close to his home at Thaketa Hospital. But like most public facilities across the country, it is barely functioning. The military occupied the hospital grounds in past weeks, causing both staff and patients to refuse to go in fear for their safety or that they will be arrested, while many of the doctors and nurses who work there are on strike in rejection of the military’s seizure of power.

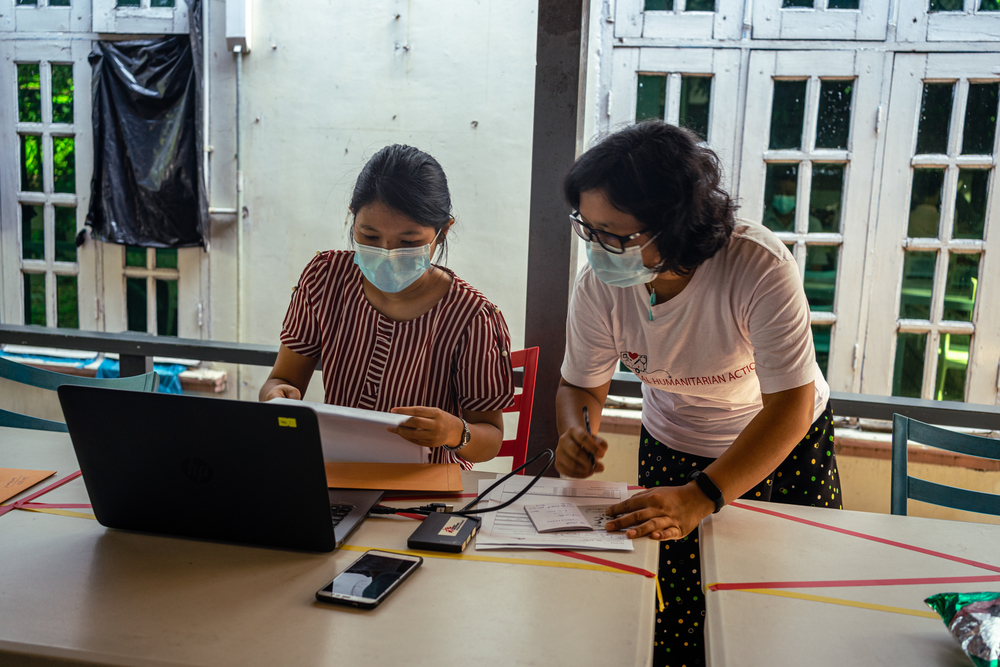

Yet stopping treatment is not an option for Ko Tin. With the hospital unavailable, MSF is using its office in Yangon to provide him and other patients like him with consultations, blood tests and medication.

“These patients have complex and serious conditions, and that is why we must continue to see them. If they do not keep up treatment, their symptoms will progress, and for those with hepatitis C it can lead to serious liver conditions and even cancer,” said Dr Ye Yint Naing, Medical Activity Manager for MSF’s Yangon project.

Not only is the situation threatening patients’ physical health, but it is also taking a toll on their mental wellbeing.

The effect on mental health

“I saw one military truck on the way to the clinic. It is not easy to go from one place to another. I don’t feel safe. I was not searched today, but I was worried,” said U Thein Aung*, a 55-year-old male patient.

“Since the coup I have struggled with depression. It is not easy to go to hospitals and clinics, even in an emergency.”

To address this growing issue, MSF is expanding its psychosocial support services across its clinics.

U Thein’s and Ko Tin’s experiences are reflective of part of a wider breakdown of Myanmar’s health system that MSF is witnessing first-hand. With medical staff refusing to work under the de facto military government, referral pathways are in disarray. There has been a dramatic reduction in the availability of basic and specialised health care.

We had been in the process of transferring our HIV patients to the country’s National AIDS Program, but since the military seized power it has been paralyzed, disrupting as many as 200,000 people’s treatment.

Over 2,000 patients who MSF had previously handed over to NAP have returned to our clinics for consultations and refills, and we are registering new patients who cannot get diagnosed and treated through the public health system.

“For HIV patients who do not get a diagnosis in time, they do not know they should be taking precautions to avoid transmitting it and cannot get the drugs to reduce their viral load. This risks spreading the infection further, worsening the situation in Myanmar,” Dr Ye Yint Naing added.

“Similarly for tuberculosis patients, if they do not get diagnosed, they do not get treatment. They will infect others and we will see the disease spread far and wide. This could roll back decades of progress in containing these infectious diseases in Myanmar.”

*Name was changed for anonymity.