South Sudan: Stagnant flood waters causing malaria peaks and hampering healthcare access

In Jonglei state, northeastern South Sudan, Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) teams are rushing four critically ill patients by ambulance boat to the MSF hospital in Old Fangak. Among the people on the boat, Nya Sibet Mar is holding her two-year-old daughter, Nya Thor, who is suffering from severe malaria.

It is the second time that Nya Thor has become infected with malaria. According to her mother, more and more people have become sick with malaria since the heavy flooding, which started in 2019.

“Two years ago, our house was completely flooded, so we had to look for another place”, says Nya Sibet Mar. “We arrived in Toch, but because there is more water than before, we live surrounded by mosquitoes. We see a lot of malaria cases now compared to before the floods.”

In Old Fangak, MSF teams are recording high numbers of malaria cases, especially among children and pregnant women. Since the beginning of August 2023, out of an average of 200 consultations per day, about 75 per cent of them result in positive malaria cases. Each day, MSF teams admit 10 to 15 patients suffering from severe malaria.

In the hospital, MSF teams see both uncomplicated and severe malaria cases, and are able to provide anti-malaria drugs, as well as treat complications such as severe vomiting, high fever, convulsions, pneumonia, anaemia and malnutrition. Nya Thor is suffering from complications; admitted to the paediatric ward of MSF’s hospital, she receives treatment for both malaria and malnutrition.

“Recurrent floods have aggravated malnutrition in Jonglei State, having destroyed crops and cattle, and forced communities to flee their homes”, explains Thomas Kun, MSF’s Clinical Officer who has been working with MSF since 2015.

“Families who used to cultivate crops now completely rely on fishing and food distributions from international aid,” says Kun. “However, due to the delayed rains, fishing is becoming more difficult, and international aid food distributions are not always consistent, meaning even less food. Children in particular suffer from this situation, not having access to food with adapted nutrients needed for their age.”

In addition to the lack of food, remote communities have been finding themselves cut-off from healthcare and mosquito net distributions, putting their lives at additional risk. Without nets, people are not protected from malaria and when they inevitably become sick, it takes several days by canoe to reach a medical facility for effective treatment. By that time, there is a risk that uncomplicated cases will have become severe ones, and pregnant women are among the most vulnerable.

“The infection can be directly transmitted from the mother to the foetus, but above all, high fever can terminate the pregnancy or induce premature labour,” explains Harriet Wikoru, MSF’s Midwife Activity Manager in Old Fangak Hospital. “We give mosquito nets at antenatal care consultations, but for mothers who live in very remote areas, their pregnancy is not monitored, and they are not protected.”

“As soon as we have a positive test for malaria, we immediately treat it,” adds Wikoru. “We cannot wait because we know the dangers of malaria for the mothers and their babies.”

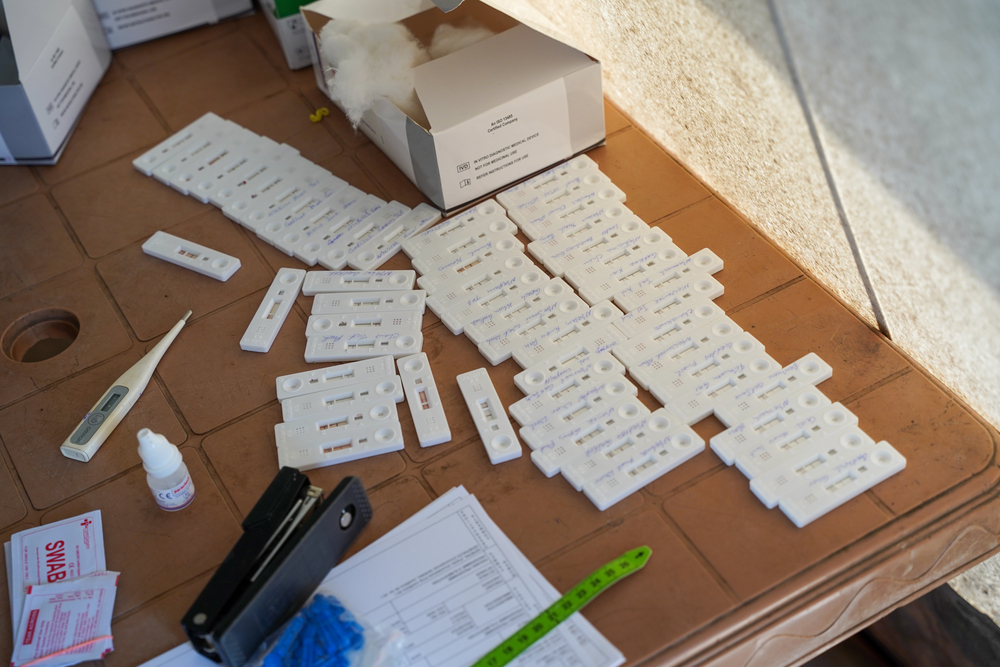

After three days under medical care in the MSF hospital, Nya Thor and her mother are brought back to their village by MSF’s ambulance boat. That day, the MSF outreach team conducts malaria screening: out of the 56 tests, 42 are positive. Some patients will be referred to the MSF hospital by the end of the day.

“Malaria is a disease for which you cannot immunise people. If mosquitoes get you again, then you will be reinfected”, explains Thomas Kun. “We keep treating and treating, but nothing says patients will not come back after one month, infected again with malaria. We provide mosquito nets and blankets, but we have already seen patients coming back two, even three times these last few months.”

Old Fangak is not the only region in South Sudan badly affected by the recurring floods. Many areas in Unity and Upper Nile states, where MSF also has medical activities, have been cut-off by floodwaters and turned into small islands with stagnant water surrounding the communities. Although this year the rainy season and expected flooding in South Sudan seem to be delayed, our teams fear that malaria cases will continue to increase. The challenges of accessing and treating patients may worsen, with expected floods isolating communities even further in Old Fangak and across the country.

To save lives from malaria – a disease that is already the biggest killer in South Sudan – there is an urgent need to help communities better protect themselves, by increasing distributions of mosquito nets and malaria prophylaxis.

Furthermore, there is a need to increase access to healthcare and prevention measures in communities, especially for children and pregnant women. As malnourished children in particular are more vulnerable to severe malaria, children should be properly screened for malnutrition, enrolled in nutrition programmes when appropriate, and receive their recommended vaccinations for childhood diseases.