Sudan: Healing in exile

Sudan war survivors in refugee camps in Chad

After the exodus and ethnic cleansing seen during the war in Darfur almost 20 years ago, the conflict in Sudan’s West Darfur state has led to more violence against Masalit communities in El Geneina, the capital city. Alongside Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) teams, photographer Corentin Fohlen provides a glimpse into the lives of survivors and families who have fled to east Chad. The faint hope of seeing the city they left behind again coexists with the refugees’ dreams and memories of those for whom the harshness of day-to-day reality in the refugee camps elicits a grim sense of deja vu.

Helping people to convalesce

23-year-old Djouwahir Abderamane is still haunted by the scenes of horror she endured while a university student in El Geneina. Shot in the head, Djouwahir emerged from a long period in hospital in April. Still partially paralyzed, she often has seizures. “The militia attacked our whole family,” explains her mother before going on to talk about the shootings in the street, torched homes and physical abuse at the height of the ethnic violence that came to a head last June, forcing hundreds of thousands of mainly Masalit people to risk everything – despite the danger – and flee to Chad. Like her friends and relatives, Djouwahir is concerned for the future. Can people recover from trauma like this? What are their prospects here, when they can’t work and moving around is so hard?

Since June 2023, MSF and Ministry of Health teams have performed surgery on over 2,000 war-wounded patients in Adré. On discharge from the hospital, some were first sent to Ambelia, a temporary camp where MSF opened a clinic to help them convalesce. The clinic offers post-surgery medical care, which includes rehabilitation provided by physiotherapists, checking fractures are healing properly, changing dressings and managing pain.

Patients also have access to mental health services.

“I work with patients traumatized by the war in Sudan. The doctors refer to us for counselling patients suffering from trauma admitted to the hospital. The mental health counsellors also identify victims of violence who require mental health support. Cases we can’t handle are referred to a psychologist or psychiatrist.”

Mental health counsellor Fatimé Djefall describes her role in Adré.

Not one, but two exiles

In late May, refugees sheltering in Ambelia camp and the wounded were transferred to Farchana, a more permanent camp. One of the first camps set up in east Chad in January 2004, Farchana has been extended to accommodate more refugees.

Adam Mohamat Khamis knows Farchana only too well as this was where he spent part of his childhood. His parents ended up in the camp after fleeing their village torched and razed to the ground by Janjaweed militias in 2003. The oldest in his family, he returned to El Geneina to study and then married. Adam was living in the city with his wife and two daughters when the escalating violence forced him to flee yet again. A week passed between the time he was shot in the arm in El Geneina and his arrival in Adré hospital in June, by which time his wound had become infected.

“I lost my arm because I couldn’t get treatment in time. We were careful to stay out of sight as we walked and kept hoping to reach the Chadian border. It was horrendous. My arm had to be amputated and I spent three months in the hospital.”

Adam

“For now we depend on food distributions.” Adam continues.

The large number of patients arriving in Adré with wounds infected already for several days is something that has stuck in Mahamat Zibert Hissein’s mind. A Chadian, Mahamat was working with MSF when, in November 2023, people wounded during the Ardamatta massacre began arriving.

“At the time, I was the only orthopaedic surgeon. There were lots of gunshot bone fractures and most were infected. I remember one particular case, a young kid who was about 15. He arrived with a tourniquet his parents had applied a week before. His sisters were with him, but not his parents. Given the state of the wound, amputation was the only option. In the operating room he said to me, ‘Doctor, you know that even with one leg, it’ll be me who’ll have to take care of my little sisters. There’s no-one else.”

Adam’s eldest daughter often asks him when they’ll be able to return home. In spite of the improvised lessons given in the camp, what she misses most is school. Her father is in charge of teaching history and geography. “This time, returning to Sudan is out of the question,” declares Adam. His wife wants them to be re-located to a secure country, like the United States. Her brother died in the Mediterranean Sea while attempting to cross from Tunisia.

A massive humanitarian crisis

In Chad, one child in every five does not reach their fifth birthday. Over two million people (out of a population of around 17.4 million) are living with severe food insecurity.

“In recent months we have taken as many as 10 refugee families into our home. We share our food with them while they wait to be re-located to camps where they can access food distributions,”

says Umsamaha Yacoub, a Chadian woman whose son is an inpatient in Adré hospital’s intensive therapeutic feeding unit.

Chadian and Sudanese children are treated in MSF’s paediatric and nutrition units, which are currently operating at full capacity with up to 130 beds.

The arrival of huge numbers of particularly vulnerable Sudanese refugees in this unstable region has exacerbated the pressure on local resources and livelihoods and, at the beginning of 2024, Chad’s government declared a food and nutrition emergency. While refugee camps set up nearly 20 years ago are chronically overcrowded and new ones that are springing up have insufficient capacity, the more than 100,000 refugees in transit in Adré have to do what they can to survive in makeshift shelters or under plastic sheeting. There is not enough water and malnutrition is taking its toll on the most vulnerable. In an effort to improve living conditions, over a year ago MSF began rolling out large-scale emergency operations to deliver medical treatment and supply water.

Mutual support and casual jobs are not enough. When so many people depend on humanitarian aid, World Food Programme distributions – which, due to lack of funding, are routinely under threat of being suspended – are absolutely vital. More and more of the refugees who cross the border to Chad everyday say they are fleeing hunger and destitution, a situation that, as the conflict drags on, is only getting worse.

When I arrived in Adré, I couldn’t find work and the food distributions weren’t enough to feed us. I used to live in Ardamatta in Sudan and, when the war broke out, I came to Adré with my 10 and 12 year-old daughters. The RSF looted everything we had. I spend my days making these bricks. For 1,000 bricks I’m paid 300 CFA francs.

Fatime Deffa Ibrahim

In Aboutengue camp we don’t even have a place to sleep. The shelters are all taken. I have no work and walking is difficult. My eldest daughter has offered to come to Adré to try and earn some money to help us buy food for our family. We fled El Geneina in June. We took nothing with us. We hid as best we could to avoid the gunfire. My sister was shot in the stomach and her husband was wounded in the head. My husband disappeared, but I managed to find him. He’d been wounded too and MSF was treating him in Chad. Four months later I decided to go back to Sudan to look for my sister’s son – the sister who was shot in the stomach – and I was told he’d been murdered. That was when I was wounded. Fighter planes were flying overhead and everyone was running for cover. My car was hit and I was taken by cart to the MSF hospital in Adré. I’ve had nine rounds of surgery. Five days ago I came back to the hospital for physiotherapy sessions to help me walk and have my dressings changed.

Iqbal Youssouf

My daughter Faiha has been on the malnutrition treatment programme for five weeks. Getting hold of food is really hard here. I have a ration card, but I didn’t get anything at the last distribution. I make bricks to earn some money while my sister watches the baby. But for a week now there’s been no work. My parents are sick, my sisters are still very little, so it’s only me who can work. Faiha’s father went missing in El Geneina. In June I was pregnant and I walked with my mother to Chad. At the end of September, I went back to Sudan to look for my husband, but the war had flared up again in Ardamatta. I gave birth to my daughter in Sudan and then came back to Chad. I still don’t know where my husband is – Saffa Abdulrahim

I’m 65 and I arrived here yesterday. We lived in a village, Abura, but in 2003 we had to move to Ardamatta. In November, Ardamatta was attacked, so we went back to our old village. But there’s nothing left to eat there. My brothers were killed in the war, the harvests have been wiped out and in the past few months it’s been really difficult to find food. I was advised to come to Adré to get treatment and, given that we’ve lost everything, register as refugees – Ashei Mohamed Ahmed

I arrived here today from Ardamatta with my mother and daughter. We haven’t been here before. Life has been tough. We kept telling each other to be patient, but we couldn’t stay any longer. The Arab militia took our donkey and we’ve lost everything – our animals and our crops. There’s nothing left to eat, so we came here. Also, as the pain in my arm keeps me awake, I’ve come to see a doctor.

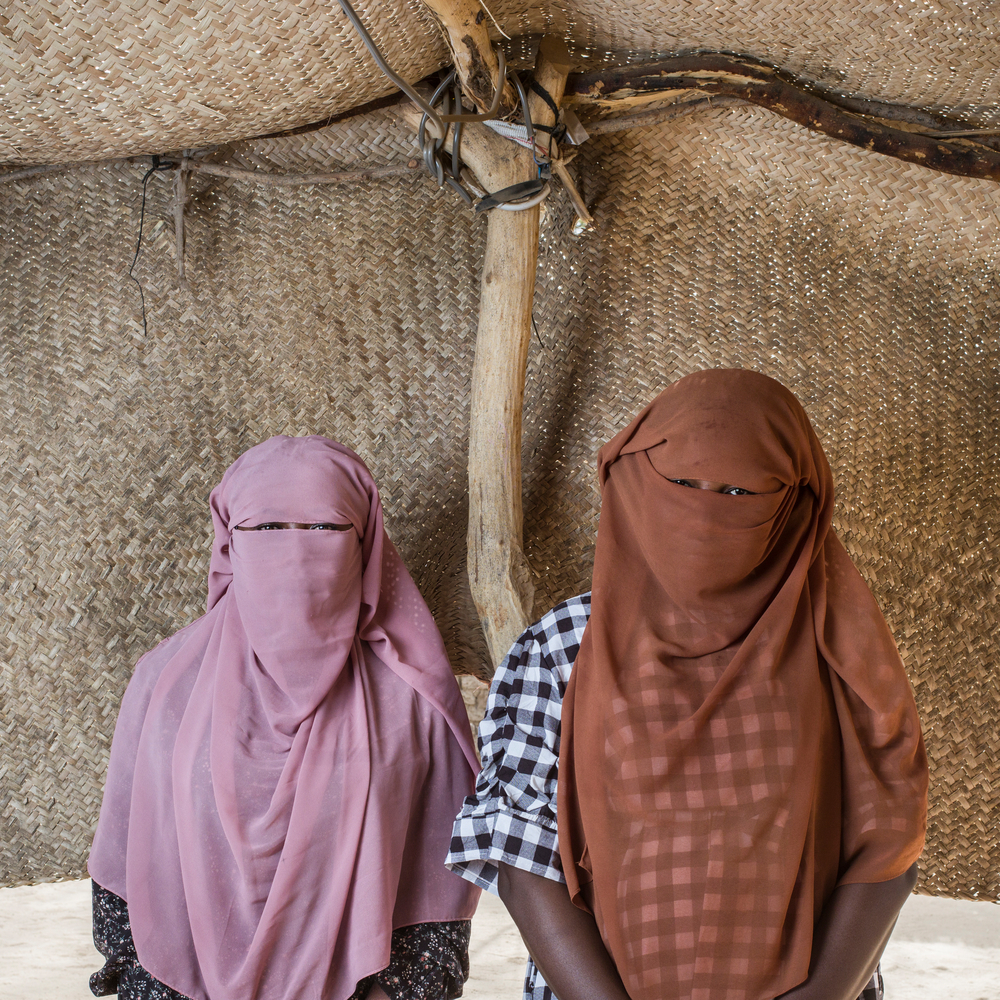

“It was me they were looking for”

Frequently only hinted at and intensified by the population’s vulnerability and precarious living conditions, sexual violence is seemingly common in the war and is spilling over into Chad. MSF provides victims with medical care and mental health support, but due to lack of information or fear of stigma, many go untreated.

Activists, social workers, medical personnel and lawyers already involved with these issues back in Sudan continue their work of raising awareness, documenting abuses and supporting victims in Chad.

An activist from the ROOTS association shares her concerns.

“We see many rape victims with suicidal thoughts. Isolated, they tell us they’d be better off dead because they’re uprooted from their country, feel rejected and don’t dare report the violence they’ve been subjected to.”

In Sudan, ROOTS managed a social centre and raised awareness to sexual and gender-based violence. They also gave advice to victims about medical treatment, informed them of their rights and guided them through the legal system.

“During the war our volunteers have kept up their work and continue to relay information from the city’s various neighbourhoods. The militias came to my house. I was a target and it was me they were looking for. When they didn’t find me, they killed my father,” one activist says.

Forced to remain anonymous, lawyers continuing their work from their exile in Chad report similar trends.

“We were on the wanted list because we were documenting violence against civilians and combatting impunity for war crimes committed in Darfur. The militias had lists with our names and photos. Numerous colleagues have been raped or killed in this war.”

The threats do not stop in Chad. Some feel insecure because they sometimes recognise perpetrators of the violence among people walking through markets or camps around Adré. Calls and messages from Sudan threatening to track them down and kill them are common. One of the activists is unwavering in their response. “They’re not going to stop us or put us off. We have every intention of seeing this through.”