Ebola: World’s second-worst outbreak nears end in DRC

By Karline Kleijer, Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) Head of Emergencies

Today as the world is focused on the Corona Virus pandemic, the world’s second-worst Ebola outbreak is finally nearing its end.

Over the past months the number of Ebola cases finally dwindled. Having lasted over 18 months and resulting in the deaths of over 2,250 people, we are now in a countdown to the end, with the last confirmed Ebola patient released from treatment in early March.

Yet despite relief that this outbreak might finally end soon, this is no time to celebrate. We cannot label the Ebola response a success.

In fact, this cannot be labelled as anything other than a systematic and catastrophic failure that left thousands dead.

Ultimately, we failed the people of DRC.

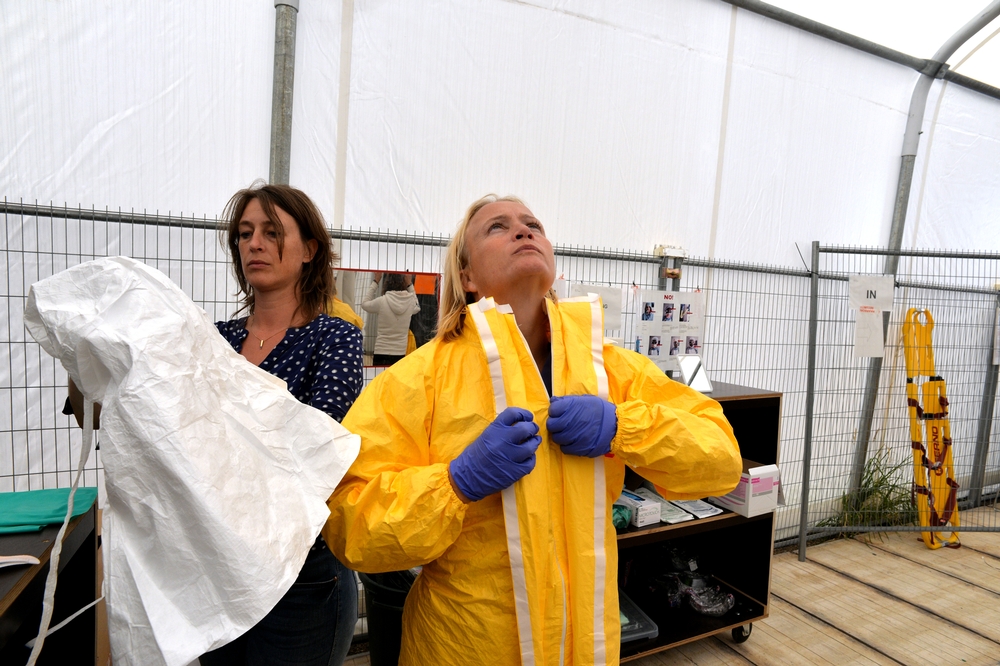

Following the declaration of the epidemic on August 1 2018, a massive United Nations and Ministry of Health led response, or ‘riposte’, was rapidly launched, aided by tools that were either unavailable or severely limited in previous Ebola outbreaks, such as new investigational Ebola vaccines and therapeutic treatments.

Yet despite this, the outbreak lasted more than 18 months, and the mortality rate remained very high, at 60-70% throughout. This is higher to the mortality rate in the 2014-2016 West Africa outbreak, when such experimental treatments or vaccines were not, or rarely, available.

Critical questions

Critical questions must now be asked to all actors of the response, including MSF, the World Health Organization, Ministry of Health, the DRC authorities, United Nations leadership, donor countries and international NGOs.

Why did we have a mortality rate higher than West Africa, when we had all these new treatments and vaccines available?

Why were communities attacking Ebola healthcare workers and Ebola Treatment Centres?

Why did it take over 300 attacks on healthcare workers and centres for something to change?

Yes, this outbreak was the first to take place in an area where there is active conflict, poor access to health care and other massive needs. There is no questioning this complex context imposed many challenges and barriers which hindered the response, including vaccination impeded by a struggling surveillance system often paralyzed during periods of intensified violence and, displacement of people which made it more difficult to do contract tracing and control transmission.

We know the narrow, siloed Ebola-centric approach adopted by the intervention early on, along with aggressive coercive measures, were crucial factors in the Ebola response’s failure, as we simply failed from the outset to earn the trust of the community.

Too much focus was placed on containing the virus instead of supporting the affected people. And without the trust of the community, we set ourselves up to fail the people of DRC.

We saw time and time again existing international Ebola capacities such as laboratories were not utilised despite the existing massive gaps on the ground.

There was massive mobilization of financial and human resources for this response. Why did those who had unfettered control over these resources – such as the Ministry of Health and WHO – not adjust the response properly and timely, when it was clear it was not effective?

Right now, as the first cases of COVID have surfaced in DRC, the focus needs to be about fully ending this Ebola outbreak and responding to the unmet needs of the ongoing humanitarian crises in the country. However, it is paramount for all actors of the response, including MSF, to critically reflect not only how we failed, but what system failure lead to it to avoid the same failures in the future.