Sudan: In search of a missing scarf amidst destruction

MSF advocacy coordinator Suha Diab reflects on returning to Sudan and a city changed by war.

This summer, when Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) asked if I was interested in going back to Sudan, I said yes, in a heartbeat. I had lived and worked in Sudan during a previous assignment with MSF from September 2021 until March 2023 — long enough for Khartoum to become familiar: the tea ladies, the falafel vendors, the late-night rooftop conversations after work. It was a city that grew on me quietly, until it felt like home.

When I ended my assignment in Sudan on March 31, 2023, I left behind a suitcase at the MSF apartment in Khartoum, expecting it would be sent to me soon after. Inside were two things I cared about: an indigo-blue scarf from India that a dear friend had given me years earlier, which I wore on every project visit, and a brown leather bag with black-and-white print — a goodbye gift from my Sudanese team when I finished my assignment. The war, which broke out unexpectedly for many of us in April 2023, changed everything. Assumptions that life would continue as before vanished overnight.

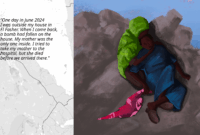

The stories they told me were harrowing: fleeing under gunfire, negotiating passage at checkpoints, whispering rushed goodbyes or risking dangerous border crossings to deliver their loved ones to safety.

Nearly 13 million people have now been uprooted across Sudan, a number roughly equal to one-third of Canada’s population. Almost 4.5 million have been forced across borders, while millions more live in fragile conditions exposed to preventable but deadly diseases. What began as a struggle for power quickly became a war on civilians — a conflict defined by siege warfare, drone strikes, starvation and the systematic destruction of essential services. Almost everyone who fled Khartoum returned later to find their houses looted, some finding nothing left but bare walls.

When I arrived in Port Sudan on June 3, 2025, the city felt both familiar and foreign. The heat was suffocating, the air heavy with salt — nothing like Khartoum. But among the staff were a few familiar faces from my earlier time in Sudan, people whose lives had changed dramatically in the two years since I had last seen them. Almost all of them had been displaced during the assaults on Khartoum and other major cities in 2023 and 2024. Many had relocated their families to neighbouring countries.

The stories they told me were harrowing: fleeing under gunfire, negotiating passage at checkpoints, whispering rushed goodbyes or risking dangerous border crossings to deliver their loved ones to safety. Some were beaten, intimidated, interrogated or even imprisoned — not for anything they had done, but because they were suspected of supporting one side of the conflict or the other, simply for doing their jobs as medical staff. From drivers to doctors, no one was spared. Each story carried its own weight of courage, loss and exhaustion.

A couple of weeks later, in mid-June 2025, I travelled to Khartoum with a colleague. Our first stop, Omdurman, seemed almost calm. But crossing the bridge the next morning changed everything. Khartoum was unrecognisable — a city hollowed out by war. Burned cars blocked the roads, buildings were riddled with bullets and entire neighbourhoods stood silent. Places I once knew — Afra Mall, Riyad, Khartoum 2 — were destroyed beyond recognition. Even the stray cats and dogs were gone.

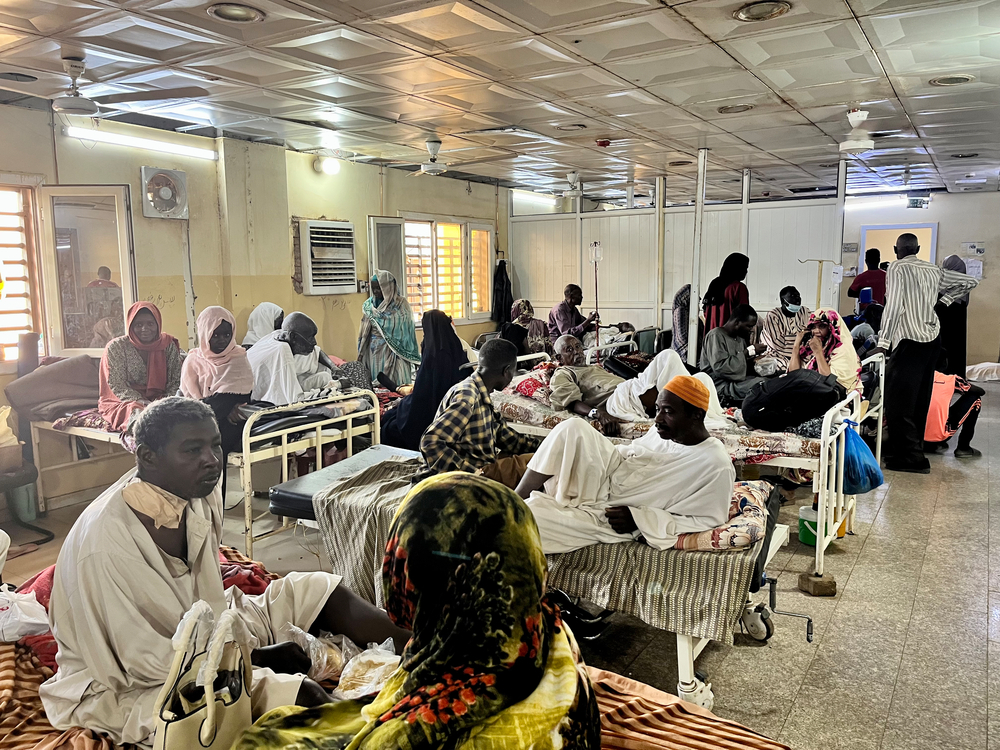

More than a million people have reportedly returned to Khartoum State, but they have come back to a city with little to return to: contaminated water systems, streets littered with unexploded ordnance, burned markets and almost no functioning healthcare. Hospitals that once formed the backbone of the health system have been destroyed, occupied or abandoned. Cholera, dengue, measles and malaria continue to spread in cycles, fuelled by displacement, lack of clean water and the collapse of disease surveillance. Acute hunger has surged: over 20 million people now face crisis-level food insecurity. The country’s health system, already fragile before the war, has largely collapsed and rebuilding it will take years.

Twelve days after the fall of El Fasher on Oct. 28, 2025, I left Sudan again, with a heavy heart. Reports of massacres, burned camps for displaced people and executions of civilians continued to surface. Atrocities were unfolding in real time, met with silence and recycled statements of concern. It is staggering how little we learn from our own history — how often the world waits until atrocities are undeniable, until it is too late to act and then responds reluctantly, if at all. As fighting spreads into Kordofan civilians are once again trapped between drone strikes, siege, disease and starvation.

Because in that quiet insistence on hope, even amid the ruins, lies the resilience that has kept Sudan alive.

I never found my bag. Between contamination risks and administrative restrictions, returning to the old MSF apartment was impossible. Some of my international colleagues teased me, saying they probably saw my blue scarf “flying somewhere” in Khartoum’s stolen-goods market — a sprawling market where looted belongings, from refrigerators to children’s clothes, were openly sold during the war. My Sudanese colleagues, though, urged me to keep hope — not out of naïveté, but because they genuinely wanted me to find it and believed there might still be a chance, however small.

I like to think they’re right. Because in that quiet insistence on hope, even amid the ruins, lies the resilience that has kept Sudan alive. And maybe, just maybe, this war could end — if those with the power to stop it truly wanted to, the same actors whose weapons, funding and silence have kept it going.