Glimpses into the Fight Against Drug Resistant Tuberculosis (DR-TB)

In Mumbai, MSF runs an independent private clinic to treat drug-resistant tuberculosis (DR-TB). India has one of the world’s highest burdens of TB, and Mumbai is a hotspot for the disease. Here, MSF’s clinic focuses on extensive drug-resistant cases, a form of the disease that has limited treatment options. The team uses newer drugs in combinations to offer all-oral, less toxic and more effective treatment regimens.

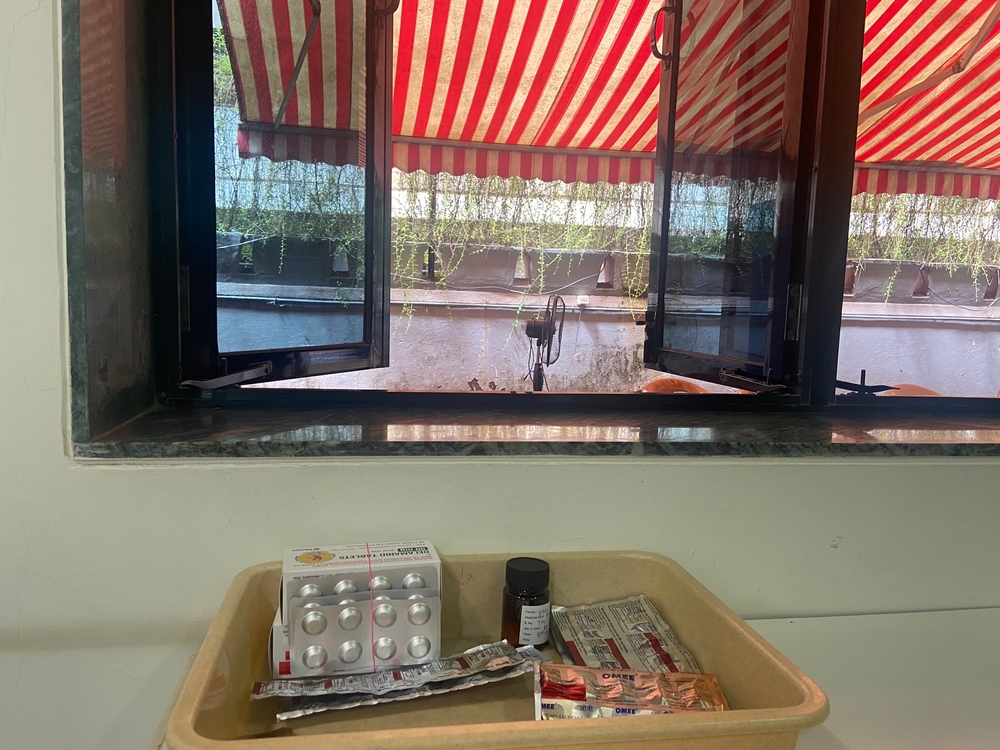

It is Friday morning in Mumbai and dappled light is streaming into the outdoor waiting area of MSF’s DR-TB independent clinic, filtered through the striped canopy roof. Today is pediatrics day at the clinic, and MSF staff are already busy welcoming caregivers and patients inside. Many of these patients are under 10 years old, like Kavya*, five years old, who is here with her mother, Samira, and her younger brother, for a follow-up appointment.

Children under 10 are particularly vulnerable to TB due to their lower immunity, especially those who are malnourished, and there are large gaps in diagnosis, case finding and treatment of children. Diagnosing TB can be particularly difficult in young children, as they may be unable to produce sputum and the disease is often found outside of the lungs, which is known as extra-pulmonary TB.

This was the case for Kavya, who was diagnosed as multidrug resistant TB in December 2022 after she developed a lymph node on her left leg. She started medical treatment in the public health system’s TB program but was eventually referred to the MSF clinic where she was initiated on a newer, all-oral, drug-based regimen.

According to her mother, Samira: “She was very weak and was not eating, and became very irritable, crying often. I was very concerned about her health, but the counselling I received at the MSF clinic was helpful.”

Now, Kavya is bursting with energy.

She knows her way around the clinic, opening cupboards and gathering colouring books and crayons as her mother speaks with the MSF nurse and receives instructions for at-home treatment. The clinic is designed to be child friendly, with walls painted bright yellow and decorated with posters of animals or superheroes, glossy purple chairs, and cupboards brimming with toys.

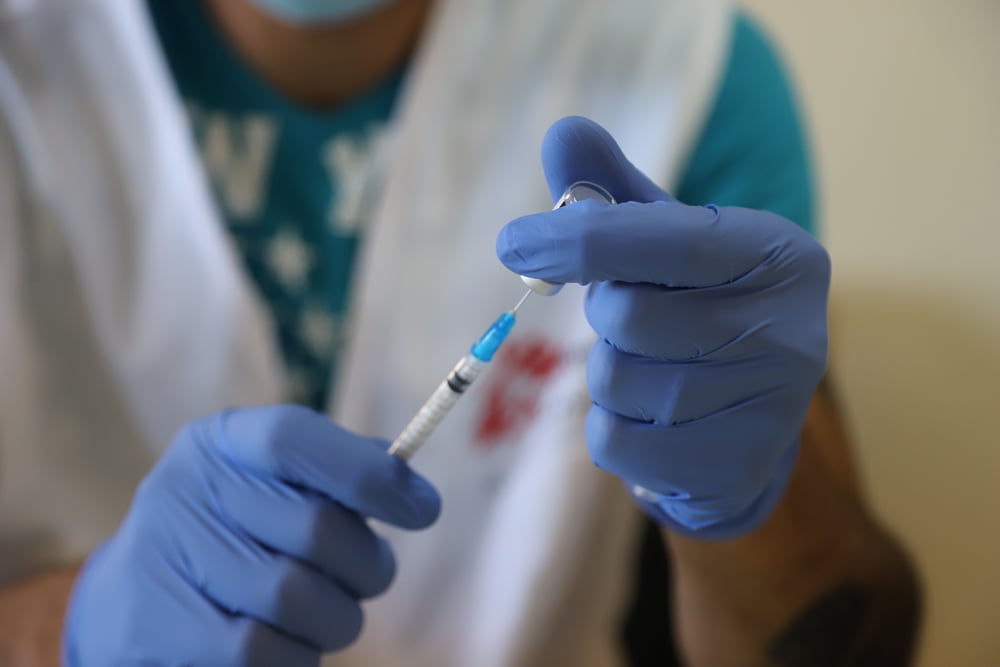

Dr Aparna Iyer, Medical Advisor for MSF’s DR-TB project in Mumbai, explains: “We focus on the pediatric cohort because they are very vulnerable, and we see that there is a huge gap in diagnosis and treatment of children. To address those gaps, we see a real value in investing in active case finding in young children, that is under 10 years of age, while also providing age-appropriate counselling tools and ensuring all-oral, less toxic regimens instead of painful injections.”

MSF’s clinic provides treatment options for patients referred by the public health system after standard TB regimens have failed. Here, they are given an innovative treatment combining two drugs, delamanid and bedaquiline. MSF’s DR-TB project was instrumental in the inclusion of the use of these two drugs in combination in the new WHO treatment guidelines published in 2020.

Dr Vijay Chavan, MSF Medical Technical Focal Point, explains: “The world is moving toward shorter regimens for DR-TB, from longer regiments of 18-20 months to reduced treatments of 12 months and even shorter such as 6-9 months. These regimens have ushered in new hope for patients – it’s a shorter duration, the drugs are palatable, they don’t have many adverse reactions, and they are all oral so there is no injectable.”

These new developments in treating TB are an important reminder that the disease, which is still killing millions of people every year (1,6 million in 2021), is curable when treatment is available and accessible.

Naima, 24, is a good example. On this same Friday in mid-August, she visits the clinic for her last appointment, having just completed treatment. Naima, who lives in a western suburb of Mumbai, was diagnosed with pulmonary DR-TB in 2020.

“I started losing a lot of weight and felt very weak,” she says. “I had to leave my job because of the symptoms.”

After months of treatment in the public health system, her condition was clinically deteriorating, and she was referred to the MSF clinic. Now, after 18 months, she has successfully completed TB treatments and left the MSF clinic in the afternoon with a certificate in hand. Now that she feels better, she plans to return to work in marketing and sales.

The last decade has shown some progress, like the introduction of three new drugs, bedaquiline, delamanid and pretomanid – the first in half a century – but there are still significant gaps in access. TB was the world’s deadliest infectious disease until it was overtaken by COVID-19 in 2020 and the existing drugs and regimens are still unaffordable and unavailable in many parts of the world today.

Providing better access to lifesaving drugs, notably by lifting patents and enabling the development of affordable, generic versions, as well as developing pediatric formulations, is essential to curbing the disease.

Johnson & Johnson, the pharmaceutical company which makes bedaquiline, recently announced that it would not enforce secondary patents on the drug in 134 low- and middle-income countries, after a successful patent challenge brought by two TB survivors in India and significant public pressure by TB activists and civil society. Thanks to generic competition, the drug is now available for $130 per 6 months treatment course. The price is expected to go down further by next year. Moreover, amid public pressure, companies Cepheid and Danaher finally reduced the price of essential TB tests by 20%. These successes show the power of public advocacy to pave the way for better access to essential drugs.

There is still a long way to go. Delamanid, the other TB drug used in the Mumbai project, is still priced exorbitantly high at $1200 USD for six months of treatment. But an independent research commissioned by MSF has shown that the drug could be priced between $30 to $96 USD for six months of treatment. MSF will continue to advocate for lower prices for DR-TB drugs and treatments.

Another barrier to access is the fact that not all drugs are marketed everywhere they are needed. “Neither of the new drugs being used to treat DR-TB in MSF’s project in Mumbai is sold in Canada, because the pharmaceutical companies that manufacture them have chosen not to bring them to market here,” says Adam Houston, medical policy & advocacy officer for MSF. The lack of access to pediatric formulations of TB drugs is another hurdle to equitable access to treatment, and one that disproportionately affects Indigenous communities in the North.

Canada has an important role to play in the fight against TB at home and abroad.

There are important strides being made to provide effective treatments for TB patients around the world, but these efforts are not enough and too many people are not getting the treatments they need. We will only see true advances in the fight against TB when concrete actions and global commitments are taken by pharmaceutical companies and governments to break down access barriers and prioritize people over profit.

*Names changed for anonymity