Home | What we do | Advocacy

To contribute to global vaccine equity, donations of COVID-19 vaccines must be done properly

By Adam Houston, Medical Policy and Advocacy Officer for Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) Canada

In late February, Dr. John Nkengasong, the head of the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC) was quoted in the media as saying something unexpected: calling for the world to pause donations of COVID-19 vaccines to the continent. Surprised reactions led Dr. Nkengasong to publicly clarify the Africa CDC’s stance a few days later. “We have not asked them to pause the donations, but to coordinate with us so that the new donations arrive in a way so that countries can use them,” he said. “This is very different from saying don’t donate at all.”

…the global supply of COVID-19 vaccines is no longer the sole driving factor behind vaccine inequity.

This comes at a time when the global supply of COVID-19 vaccines is no longer the sole driving factor behind vaccine inequity. That same week, it was reported that, for the first time, supply outstripped demand for vaccines from COVAX. Yet at the time these statements were reported, less than 18% of people in Africa had received at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine. By comparison, more than 84% of people in Canada had received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine, and nearly half of Canadians had received a third dose. The percentage of people receiving a third dose in the continent of Africa is so low as to be virtually unmeasurable. To fully understand this disparity, we need to shift our focus from whether doses are being donated to how those donations are being carried out.

The capacity of a country to receive and administer vaccines should not be conflated with its desire to vaccinate its population.

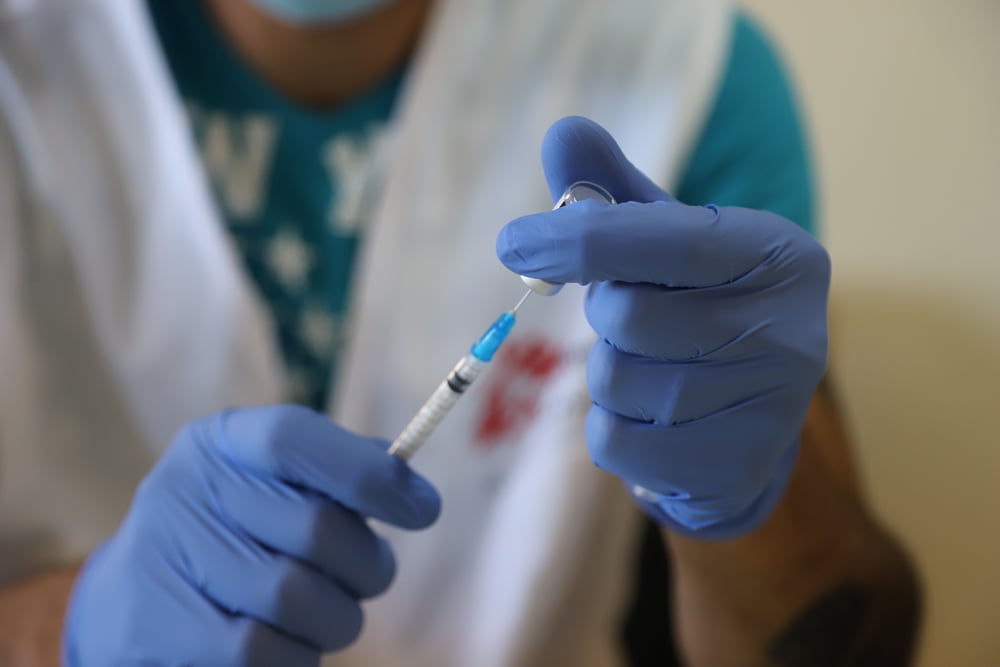

While each African country faces its own unique set of circumstances and vaccination rates have varied considerably across the continent, a common factor for many is the gulf between vaccines and vaccinations. Numerous barriers remain in getting donated doses off the airport tarmac and into the arms of those who need and want them. One of these barriers is the parallel issue of access to a dependable stock of basic supplies necessary to administer vaccines – things like syringes. Another is adequate storage facilities that can accommodate enough vaccines under the right conditions. Conditions in a capital city may be very different from in a rural area, for instance. A related issue is that of ensuring an unbroken cold chain stretching from where doses arrive to where they are needed. Having all the pieces in place to make the final journey to the recipient’s arm – the so-called “last mile” – is crucial to solve this puzzle. Canada has recently highlighted the importance of addressing delivery and distribution challenges; however, it is important that this interest translates into tangible action.

The capacity of a country to receive and administer vaccines should not be conflated with its desire to vaccinate its population. To put it another way, obtaining COVID-19 vaccines is a bit like buying milk from the milkman. You want deliveries to be predictable and reliable; it’s hard to plan breakfast if you don’t know when you’ll next have milk in your fridge. At the same time, you don’t want to have more than you can use before it expires (expiry dates are at least as important on vaccines as on milk cartons, if not more so. You also want to make sure you have room in your fridge to keep it cold and ensure it doesn’t spoil. If the milkman offers to drop off a year’s supply of milk at your house, you’re probably going to say no; it’s unlikely you’ll have anywhere to put it, let alone the ability to use it before it goes bad. Indeed, receiving so much at one time, particularly when there’s not enough room in the fridge, will practically ensure it will go to waste. Instead, getting only the amount you need at one time, knowing the milkman will remain a steady, reliable source to meet your needs and replenish your supply when you need more is a far more effective approach in the long-term.

As such, it is not surprising that the Africa CDC wants to ensure that donations are better coordinated with the needs and capacities of recipient countries, ensuring doses do not go to waste. As Dr. Nkengasong, says, “It’s not to say that donations are not important. It’s just to say let’s not just do it at once”.