How malnutrition is dangerously feeding the TB/HIV pandemic in South Sudan

In South Sudan, over seven million people are expected to face acute food insecurity or worse between now and July. Among them, patients who are infected with tuberculosis and HIV are highly impacted since the intensity of the treatment is very hard to bear on an empty stomach. Some of them endure severe pain, while others decide to reduce or even stop the medication to make it more bearable; putting their lives at risk.

Nobody should have to choose between taking life-saving medication and living pain free. Yet, this is the situation that more and more patients infected with tuberculosis and HIV must face in Leer, Unity State. While their medical treatment can involve up to eight pills a day and lasts for the rest of their lives, patients have to cope with a lack of food, which can cause severe pain and dizziness. They then have to choose between taking the medication and suffering on a daily basis or stopping it and seeing their health deteriorate.

Standing feverishly in front of his house in the 40-degree sunshine, James, a 60-year-old patient, holds a cane to support his emaciated body: “Life is very hard here because we have nothing. I fell sick with TB/HIV three months ago, so I can’t do any work and I have no savings. All we find around us are water lily roots, but that’s not enough”. Showing his stomach with a grimace, he continues: “That’s why I usually reduce my treatment to adapt to the food I eat. If I see that I’m only going to have one meal a day, then maybe I take half my medication. I know that’s not good for my health, but I have no other choice. If I take the treatment without eating, I get dizzy, shiver and have severe stomach pains.

A vicious circle that’s hard to break

Inside Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF)facilities, Gatkuoth, a new patient admitted two days ago shares the same challenges. “I had TB four years ago already, but at that time I completed the treatment quite easily. Now that the situation is deteriorating, it’s much harder because I have no food. Sometimes it’s so bad that I wonder why I kill myself with the pain, maybe I’d rather die from the disease”.

Prone to heavy flooding and recurrent insecurity, Leer County in South Sudan, is a fairly isolated and difficult place to live. For several years, people have been reluctant to cultivate their land for fear of losing it all, again. They therefore depend either on the food available on the market, which inflation is making it increasingly difficult to buy, or on food assistance, which has been considerably reduced due to budget cuts. On the top of this, population displacement from a war-torn Sudan is putting further pressure on food supplies in the area and increasing healthcare needs. Since April 2023, more than 60,000 people – returnees and refugees – have settled in Unity State.

As a result, under nutrition spreads throughout the population, creating a vicious circle. On the one hand, it can have a direct impact on adherence to TB/HIV therapy, as the intensity of the treatment is very difficult to bear on an empty stomach, and on the other hand, it is a major risk factor for disease, as immune defences are considerably reduced. Food and Nutrition support for TB and HIV patients (apart from other support mechanisms e.g. transport) is one of the keys ‘treatment enablers’, which has proven to improve patient health condition, influence adherence to treatment, and the overall outcomes.

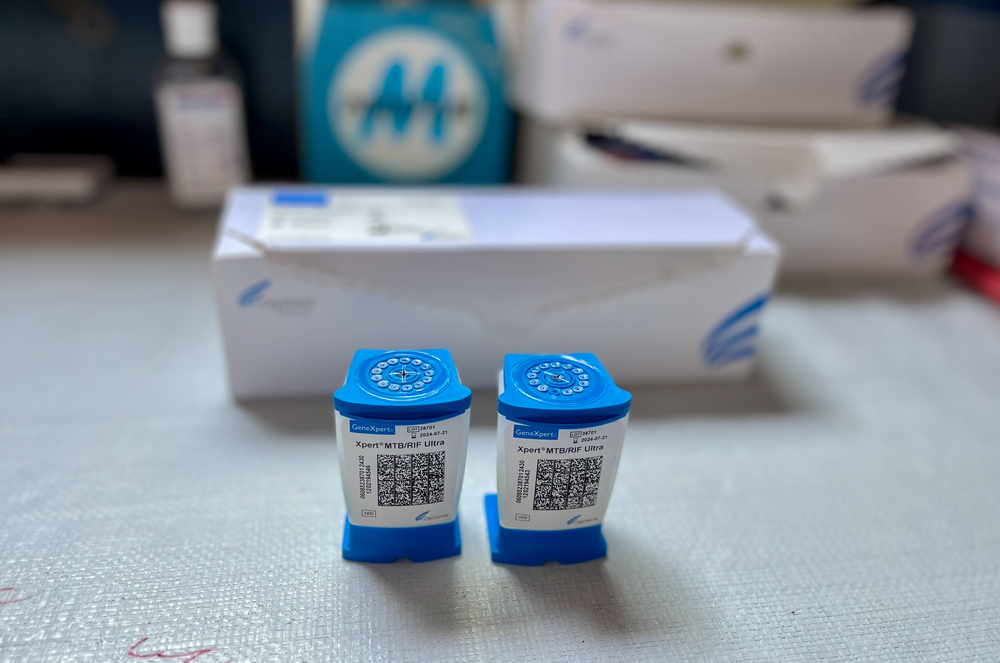

Vulnerable groups must not be forgotten

“Food insecurity is becoming a problem,” explains Daniel Mekonen, MSF’s medical team leader in Leer. “We have a cohort of more than 600 patients co-infected with tuberculosis and HIV, and many of them tell us that they can no longer follow the treatment properly because of the lack of food. They either reduce it or stop it until the situation improves. This is not without consequences. We are receiving more and more patients at an advanced stage, in a serious condition, who are becoming very difficult to treat, and others are developing resistance to antimicrobials. We used to see eight new patients a month, but recently that figure has doubled, and risen to 16 a month. We see that the defaulter rate is increasing. If people are not supported with food, our program will not succeed. On a national level, MSF is deeply concerned about the ongoing prevalence of HIV/TB in South Sudan.”

MSF who started working in Leer, Unity, in 1989, remains one of the few organizations providing medical care to the people in the area. While malnutrition is rising, insufficient food distribution is made among the population, without any priority criteria. Other organizations and agencies providing food support and assistance should scale up and consider how to specifically target and prioritize vulnerable groups such as HIV/TB patients.