Borno state: In the face of the COVID-19 pandemic, malaria, malnutrition and water-borne diseases will not relent.

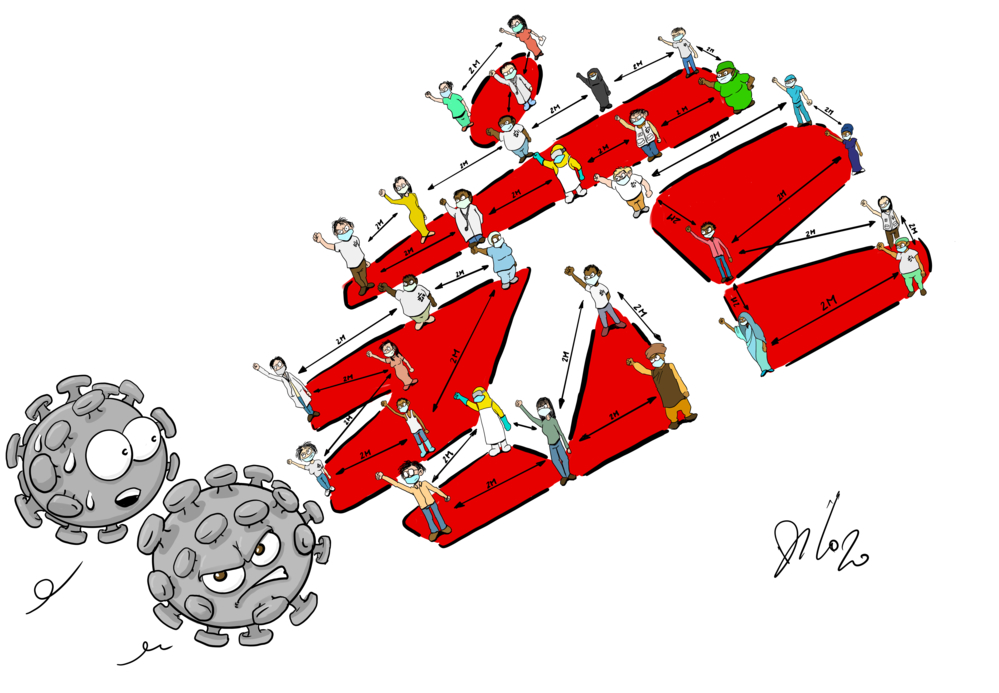

After more than a decade of armed conflict, outbreaks of severe malnutrition, malaria, measles and cholera, approximately 1.5 million internally displaced people (IDPs) in Borno state now face the spectre of COVID-19. Many live in vastly overcrowded camps with poor water and sanitation facilities, limited supplies of hygiene essentials such as soap and water, and often no individual space at all. Functioning health infrastructure in Borno is scarce, and the capacity to refer patients is extremely limited. With so many people already vulnerable to outbreaks of disease, essential humanitarian assistance must be maintained; water and sanitation facilities must be improved in IDP camps; and frontline health workers on whom the population will depend, must have access to personal protective equipment.

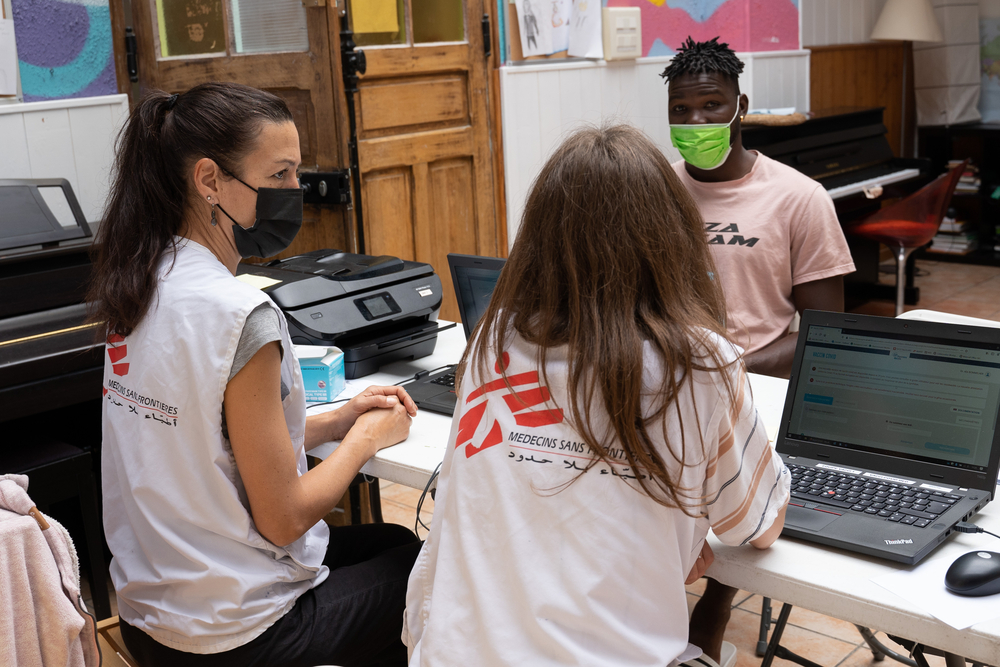

Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) has been working in Borno state since 2014, and during that time we have borne witness to deplorable conditions for IDPs, many of whom already suffer from illnesses endemic to overcrowded settlements, such as water-borne diseases and respiratory tract infections like pneumonia, which has been identified as a significant threat when coupled with COVID-19.

Mainitaining life-saving operations

COVID-19 has had a devastating effect on healthcare systems, economies and populations worldwide and it poses a substantial threat in Borno. However, even if COVID-19 were not present in Nigeria, the need for humanitarian assistance in Borno would still be massive. In just over a month, rainy season will commence, bringing with it a surge in cases of malaria and malnutrition. In Maiduguri, Ngala, Pulka and Gwoza, our hospitals run 24 hours a day, seven days a week, and during rainy season they will all be full. In 2019 alone, MSF teams treated more than 10,000 patients for malnutrition in Borno and more than 33,000 confirmed cases of malaria; over 40,000 patients were admitted to MSF’s emergency rooms. The effect that COVID-19 will have on our patients must not be underestimated, but if the chaos caused by this pandemic is allowed to curtail humanitarian assistance, the results will be catastrophic.

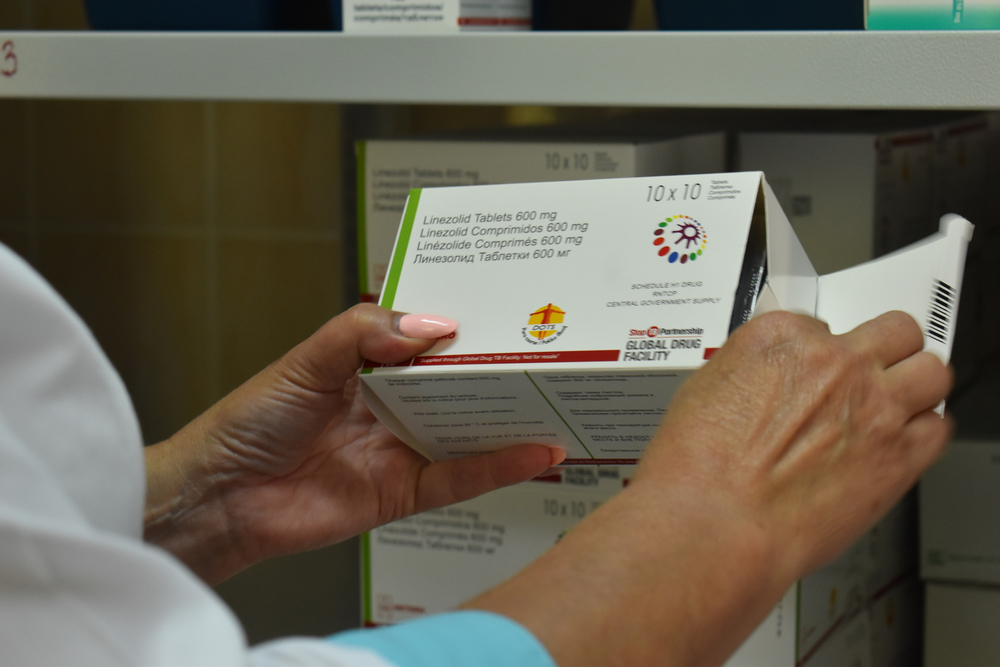

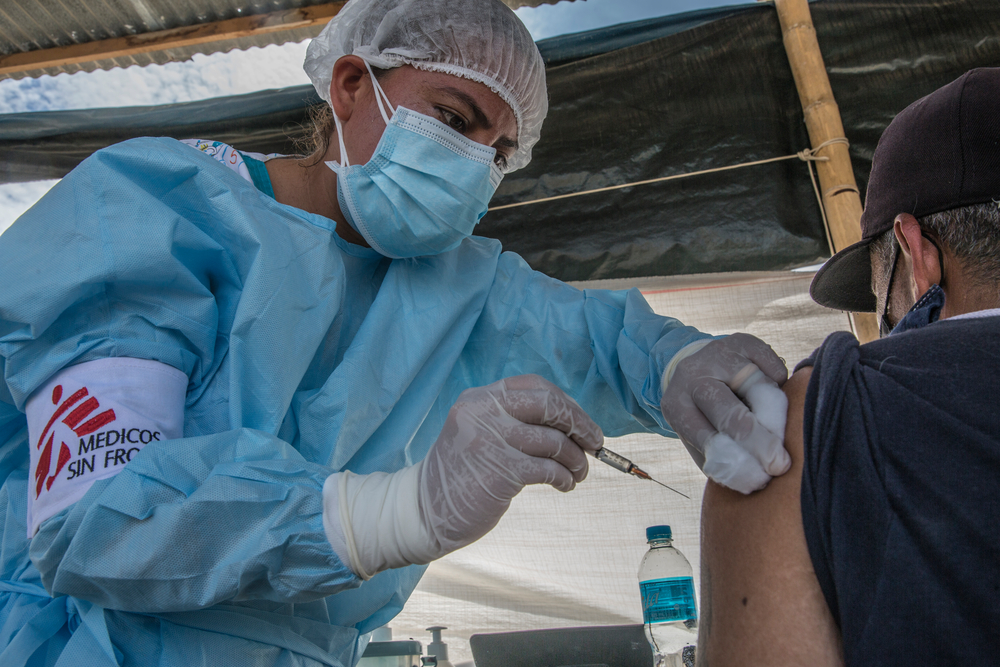

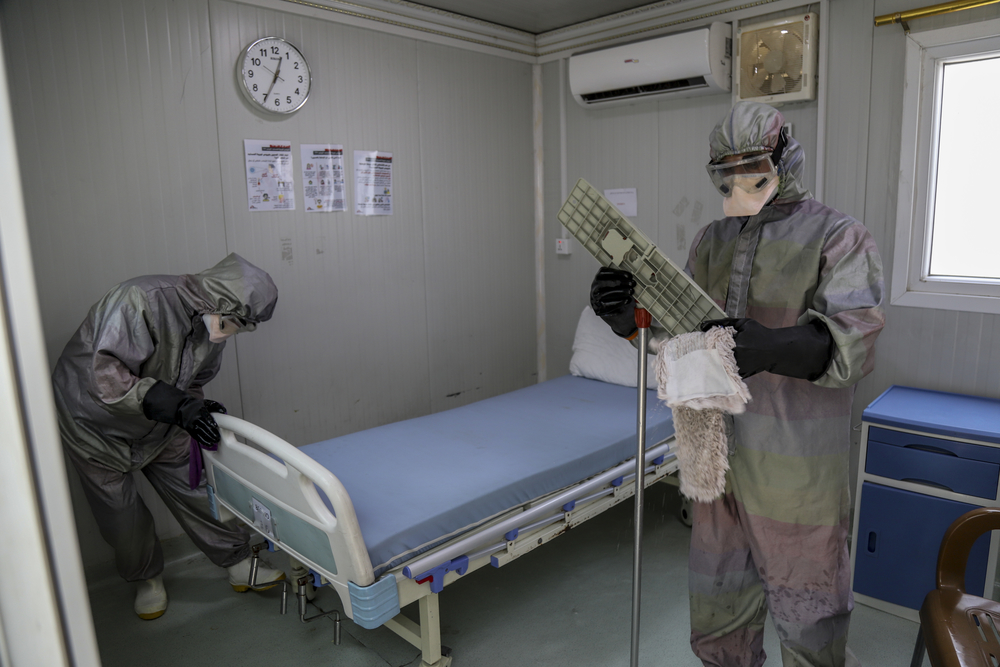

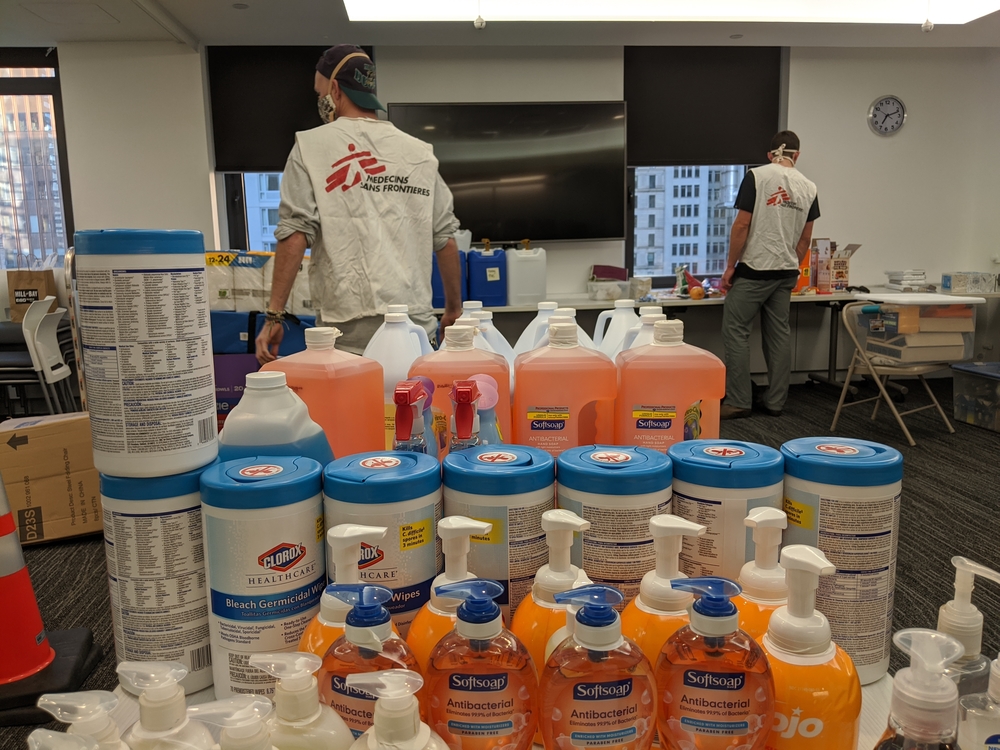

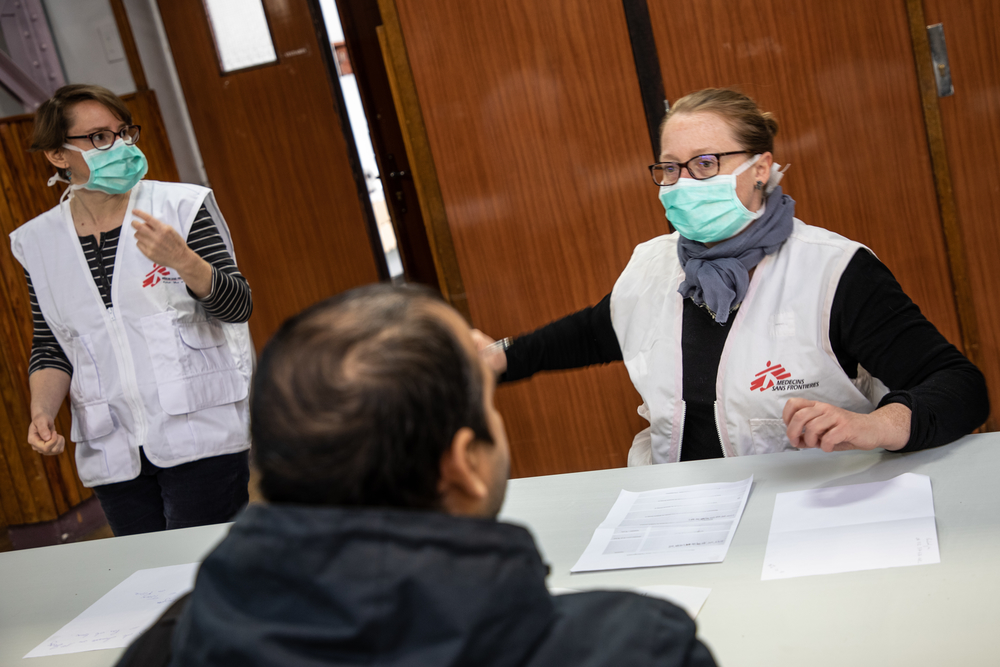

MSF is extremely concerned about the spread of COVID-19 and the potentially disastrous impact it will have on the most vulnerable. As the virus spreads in Nigeria, our priority is to maintain our operations which save thousands of lives every year, and to protect our patients and staff. To do this, our medical and logistical teams have reinforced infection prevention protocols, informed local communities on the best prevention measures against COVID-19, installed hand washing points in local communities, established isolation zones and adapted our triage processes. At a time of unprecedented global demand for medical supplies, the procurement of personal-protective-equipment for healthcare staff poses a substantial challenge, however it is a challenge we must face in order to protect frontline medical workers and continue treating our patients.

Clean water: a precious and limited resource

In Pulka, where MSF runs a comprehensive hospital with outreach activities, surgical capacity, maternity care, and treatment for sexual and gender based violence, the situation is dire. Pulka is a garrison town; a population centre controlled by the Nigerian military. It is now home to approximately 63,000 people, 78 percent of who have been displaced at least once since 2015. There are 27,000 people living in overcrowded IDP camps in Pulka with limited access to basic services, including water, food and healthcare. In both Pulka and Gwoza (a neighbouring garrison town), the transit camps for new arrivals are overcrowded; in Gwoza, the transit camp population is triple the recommended capacity; and in Pulka, communal shelters host people for months or even years when they are designed to be a temporary solution for just two weeks.

In a recent water and sanitation assessment, MSF found that the daily provision of water per person in Pulka was just 11 litres, far below the minimum humanitarian standard requirement of 20 litres required for health and hygiene. Of these 11 litres only an average of two litres was chlorinated and safe to drink. Quantities as low as 4.5 litres per person have also been recorded in previous surveys:

“You have to get up early if you want to get enough water… I have seven children, and sometimes the water just isn’t enough for us to drink – sometimes we have to beg our neighbours for drinking water. Every day women at the borehole fight over it – we know there won’t be enough for everyone. – Ajia Adam, an internally displaced woman living in Pulka.

In Maiduguri, the capital of Borno state, the water and sanitation is not much better. Between 1999 and 2011, MSF responded seven times to outbreaks of cholera in Maiduguri, and in 2018, more than 4,000 people were diagnosed with cholera in 18 local government areas in Borno, Adamawa and Yobe states.

“In all the IDP settings where MSF has operations in Borno state, gaps in essential water and sanitation facilities exacerbate the threat posed by COVID-19. These gaps, combined with the levels of overcrowding, and endemic health issues with a lack of corresponding health infrastructure, underscore the vulnerability of the population. There is no doubt about the danger posed by COVID-19, however, one thing we know for sure is that other diseases and medical conditions will not relent. We cannot afford to let this pandemic disrupt other medical assistance – the continued provision of medical services at this time is essential and it will save lives.” – Siham Hajaj, MSF Head of Mission.

COVID-19 is not the only threat facing people in Borno state, but its presence in Nigeria highlights the extreme vulnerability of so many who have already endured the horrors of war, disease and malnutrition. For them, social distancing is an abstract luxury, and frequent hand washing diminishes a precious resource. In the face of this pandemic, the ramifications of Borno’s fragile health infrastructure are clearer than ever. It is imperative that humanitarian assistance be maintained for this population. Failure to do so will cost lives.