COVID-19 in France: Ensuring continued access to medical care for vulnerable people in Paris and the suburbs

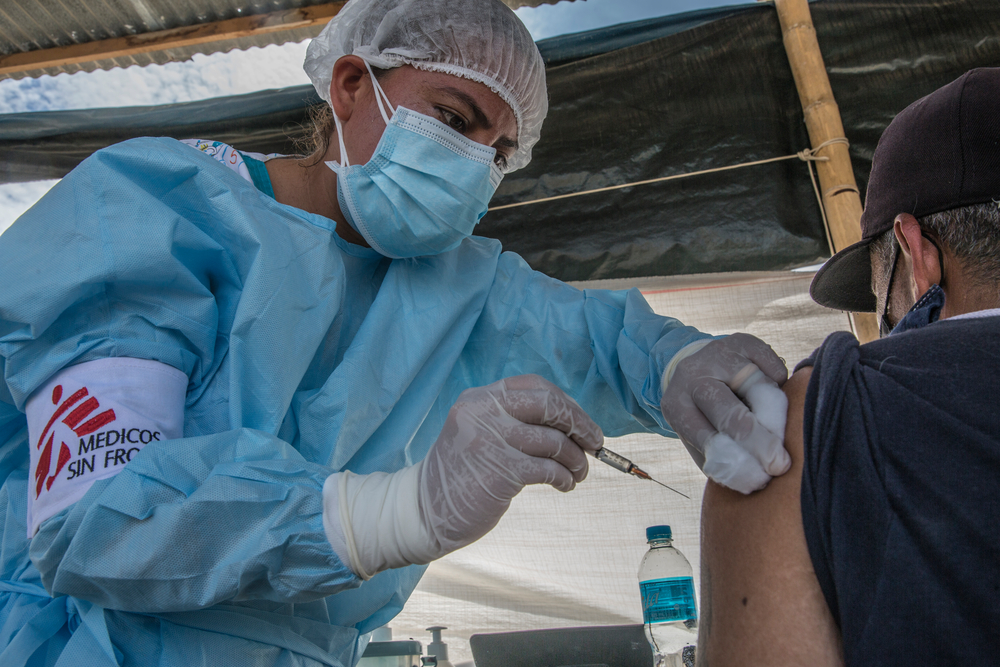

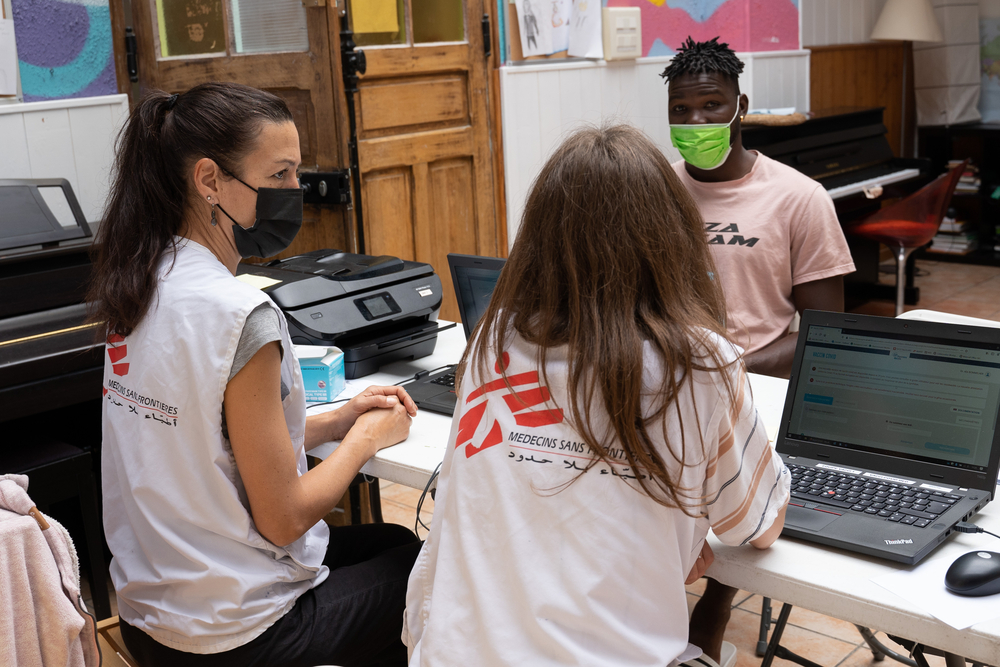

As part of the medical response to COVID-19 that continues to spread across France, last week Doctors Without Borders / Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) teams began providing medical care to vulnerable people confined in emergency shelters or still living on the streets or in makeshift camps in Paris and the suburbs.

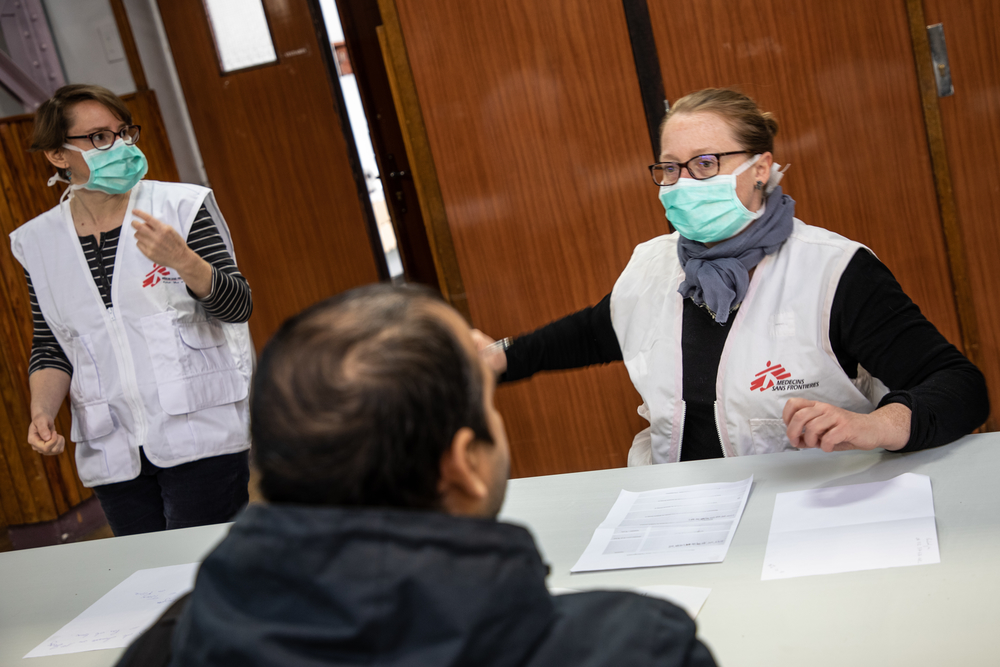

On March 24, over 700 migrants evicted from a squalid encampment in Paris suburb Aubervilliers were taken to gymnasiums and hotels requisitioned by the Paris Police Prefecture where they will be confined until the lockdown is lifted. At the request of the Regional Health Agency, MSF teams have visited six of these emergency shelters to give everyone medical examinations and detect people showing signs of COVID-19. Of the 338 people who had consultations, 25 were identified as having symptoms corresponding to those of the virus. They are now isolated and under medical supervision.

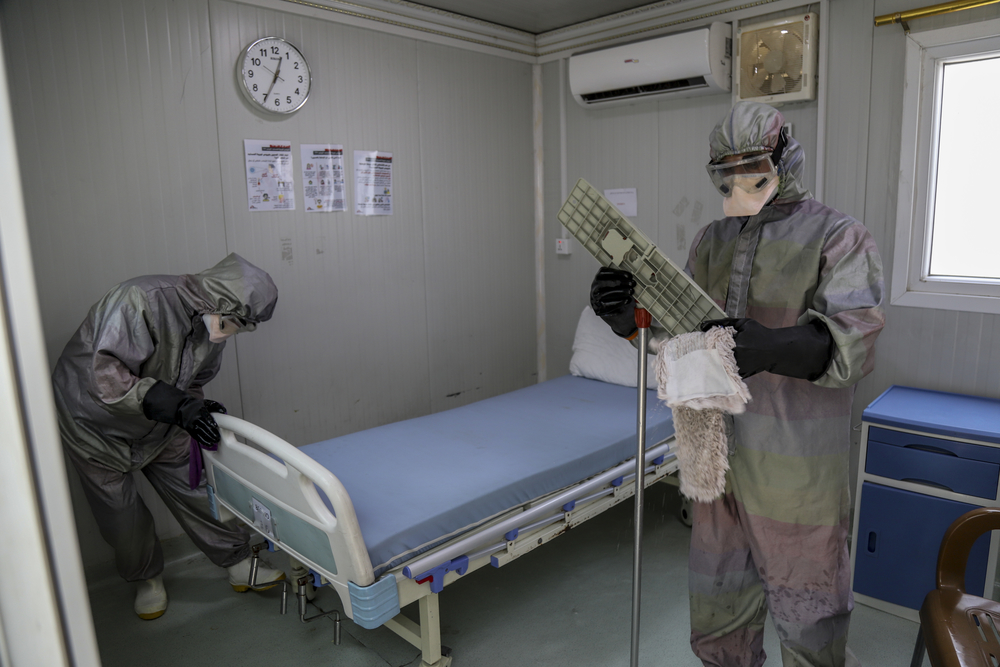

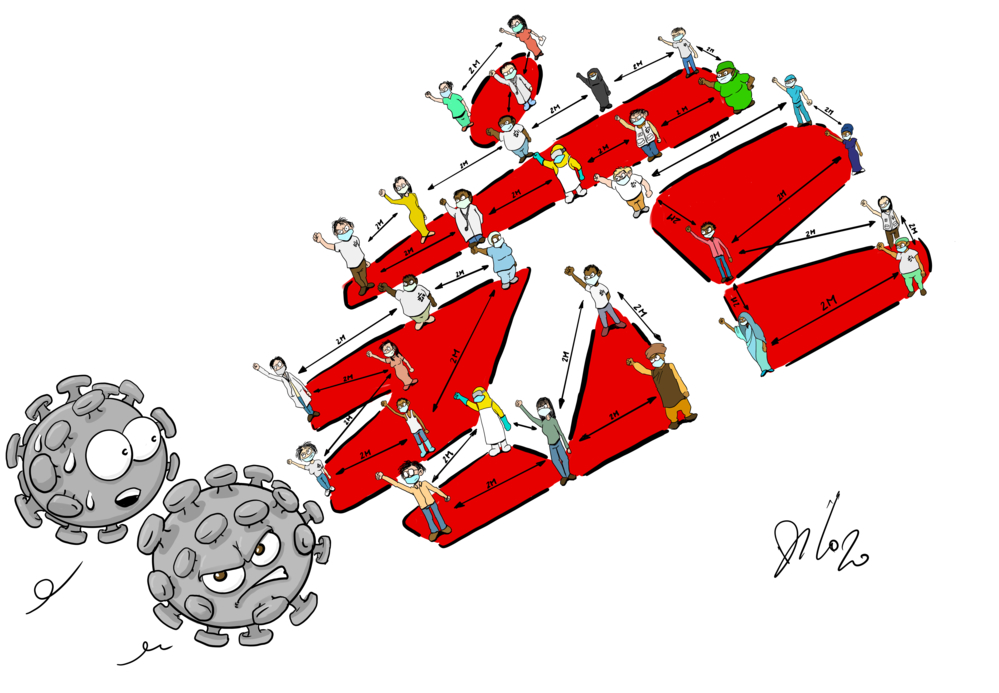

Emergency shelters enable people to be confined with a roof over their heads and facilitate their access to certain essential services, but they are not without their own risks. Communal living spaces, such as gymnasiums, are not suited to the basic protective and health measures required to help prevent the spread of the virus. Furthermore, in general, it is hard to ensure the isolation of people at risk of infection—a risk even greater for those with underlying, often severe, medical conditions and whose health has been compromised by years of precariousness, violence and social exclusion.

To prevent these communal spaces becoming centres of contamination of the virus—as much for the people staying in them as the social workers, health personnel and staff assisting them—, the authorities must find other solutions, hotel rooms, for example, to accommodate them. Testing must be ramped up to to confirm certain diagnoses, especially for those most at risk of developing more acute forms of the disease.

Our teams are also reaching out to people sleeping on the streets, or living in camps and squats in Paris and suburban towns to offer them nursing care and general medical consultations. Our assistance is delivered five days a week because the lockdown and other measures France has taken to contain the virus have resulted in volunteers not being able to provide as much medical and social support to vulnerable groups. Our teams treat a wide range of conditions, which ensures continuity of care for excluded people and helps avoid complications that would otherwise require treatment in hospitals under huge pressure as they respond to the health emergency.

At the end of 2017, we also began providing support to unaccompanied minors with appealing to the courts for recognition as minors and, consequently, entitlement to protection from children’s social services. For the duration of the COVID-19 outbreak in France, this support will be more medical.

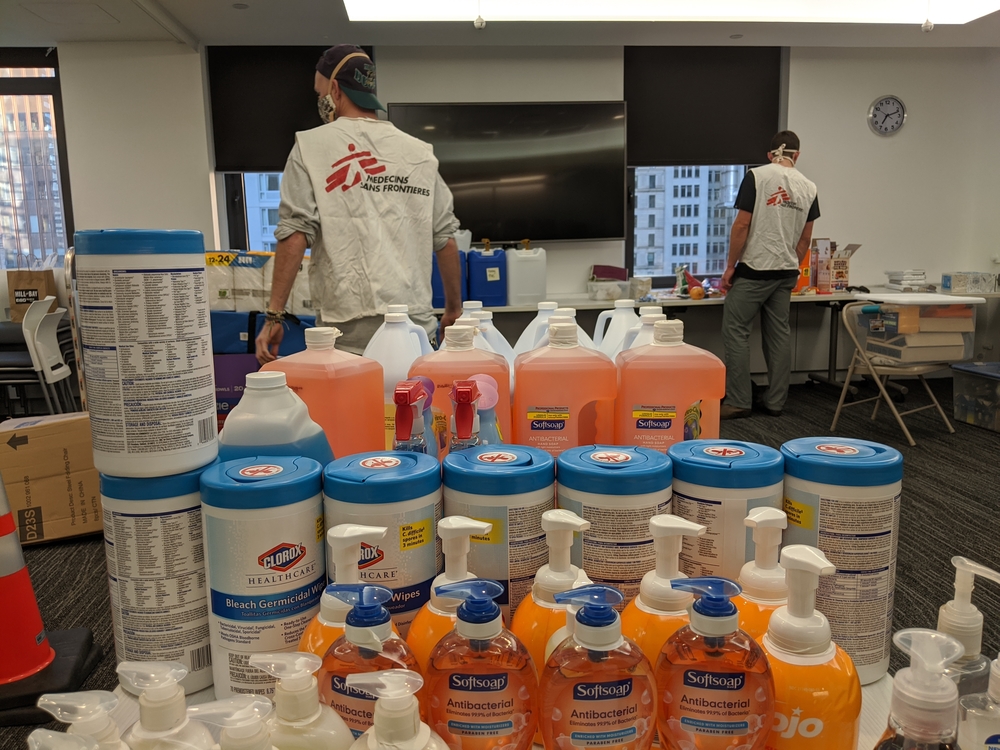

We also continue to explore what help we could give hospitals and other facilities particularly impacted by the COVID-19 health crisis. This could be technical assistance, such as helping with handling massive influxes of patients or infection prevention and control, providing staff or logistical support, such as setting up medical units in tents so that more patients can be treated.