COVID-19: Abnormality in the West Bank

A full lockdown has been in place in the West Bank for more than three weeks, with over 300 cases of COVID-19 confirmed in the Occupied Palestinian Territories. The harshness of these security measures, intended to prevent the virus from spreading further, is impacting the lives of more than 3.2 million people living in the West Bank. But while millions of people worldwide are experiencing movement restrictions for the first time, for Palestinians in the Occupied Territories, such restrictions have long been the rule rather than the exception, and have accompanied years of uninterrupted violence and political and social tensions.

“What is abnormal for the rest of the world is normal for Palestinians here,” says Tareq Zaid-Alkilani, Doctors Without Borders / Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) project coordinator in Nablus, the governorate with the highest number of violent incidents between Israeli settlers and Palestinians in 2018. “Restrictions on movement are already part of Palestinians’ everyday reality. And episodes of violence in communities around the Israeli settlements and adjacent outposts are also part of this reality. There’s no difference since the outbreak of COVID-19 started.”

The spread of COVID-19 in Israel and the Occupied Palestinian Territories has not stopped the violence in the West Bank. In March, clashes between Israeli forces and Palestinians continued – as did arrest operations, house demolitions and seizures of Palestinian properties by the Israeli army. While the Israeli and Palestinian authorities are cracking down on people’s movements and enforcing physical distancing in an attempt to curb the outbreak, attacks by Israeli settlers against Palestinians rose by 78% in the West Bank in the last two weeks of March, according to the UN.

“Episodes of physical and verbal assault, stone-throwing, damage to Palestinian property and vandalising cars, houses and agricultural property are very frequent in this area, added to routinely heavy-handed operations by the Israeli military,” says Zaid-Alkilani. “The result is a pattern of widespread, relentless violence that is taking its toll on the mental health of thousands of people and the wellbeing of entire communities. This adds to the more common causes of stress and anxiety, such as family issues or lack of financial security that Palestinians share with other societies across the world. This virus and the lockdown aren’t reversing the trend.”

Like a virus, violence has been spreading in the West Bank for decades, with communities experiencing abuse by the military and physical and psychological assaults and turmoil time after time. Under the Israeli occupation, the many different types of violence have wormed their way into domestic dynamics, creating difficulties within the home and within family relationships.

“Some of our patients, mostly those living beside the Israeli settlements, have experienced deeply distressing events,” says MSF psychologist Samieh Malhees, who has spent the past five years providing free-of-charge psychological consultations and social services to the population of Nablus governorate.

Mental health in the West bank

“One of my patients, a seven-year-old boy, has experienced sleeping problems and panic attacks ever since his village was attacked by Israeli settlers. He saw his neighbourhood attacked with stones and Molotov cocktails, and he saw people he knew fighting with the settlers. Other patients have experienced the violent loss or detention of family members, army incursions in the middle of the night and physical attacks or clashes with settlers. Many of them end up developing forms of anxiety, panic attacks and adjustment disorder. But even people who haven’t experienced such traumatic events also face the indirect disruptive consequences of all these tensions and violence.”

For the majority of people who seek psychological support at MSF’s clinics, their distress originates in the home – for example family issues and various forms of domestic violence. Sometimes, both sources of psychological disorder – the context of recurring violence and more commonplace family matters – become intertwined and hard to separate from one another.

“One of my patients told me that her husband shouts at her and the children like some Israeli soldiers used to shout at him,” says Malhees. “Another patient told me that her husband turned abusive after he was severely wounded during clashes. These cases aren’t isolated. I can trace a pattern where feelings of oppression, humiliation, powerlessness and anger due to the occupation intrude on family bonding and violence takes its course in a vicious cycle.”

The outbreak of COVID-19, the subsequent lockdown, its serious effect on the financial situation of many families, and the continuous attacks against Palestinians in the West Bank are combining to worsen the already fragile situation of people facing mental distress, domestic violence and various types of abuse.

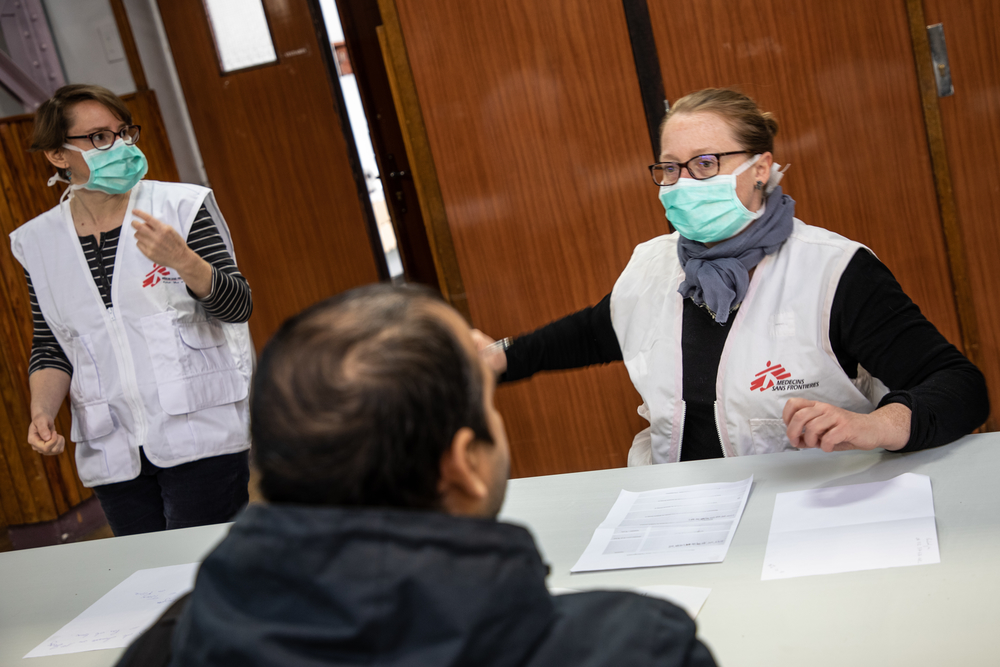

“The novelty of the coronavirus epidemic confronts everybody with the unknown, bringing a loss of control and a sense of powerlessness,” says Malhees. “Along with the lockdown, those feelings may increase anxiety and can cause uncomfortable symptoms to people with pre-existing mental health conditions. Since the lockdown started, I have been unable to meet my patients, so I try to provide regular consultations by phone. It’s hard for me as I always try to keep my family away from the heaviest side of my job. And it’s also hard for those patients who don’t have a safe space at home where they can talk with me. But we need to keep up our program. Providing psychosocial support to people already facing a load of mental distress is of the utmost importance now.”

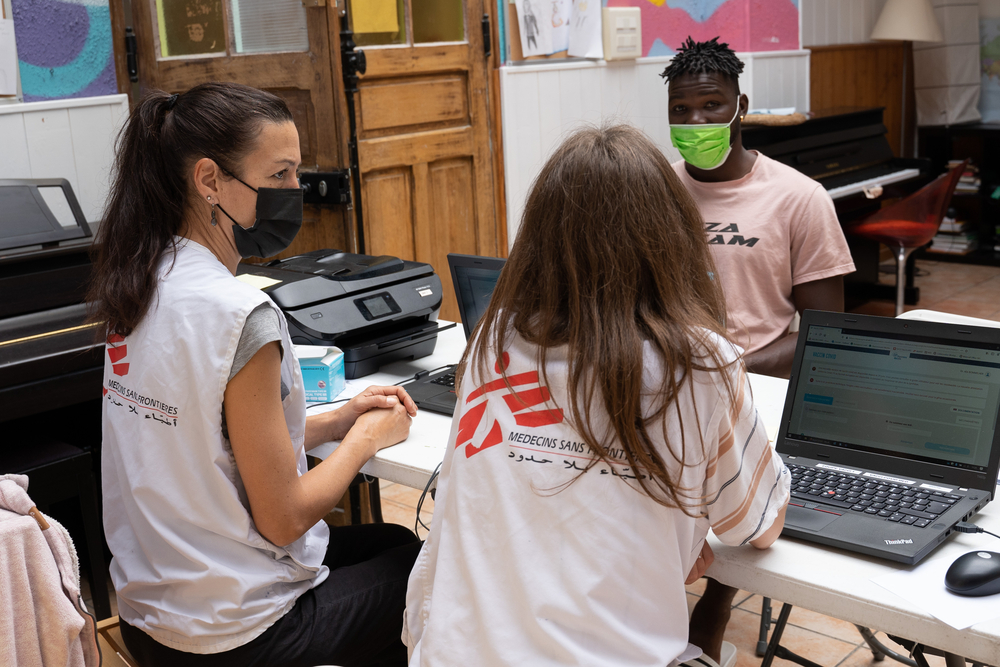

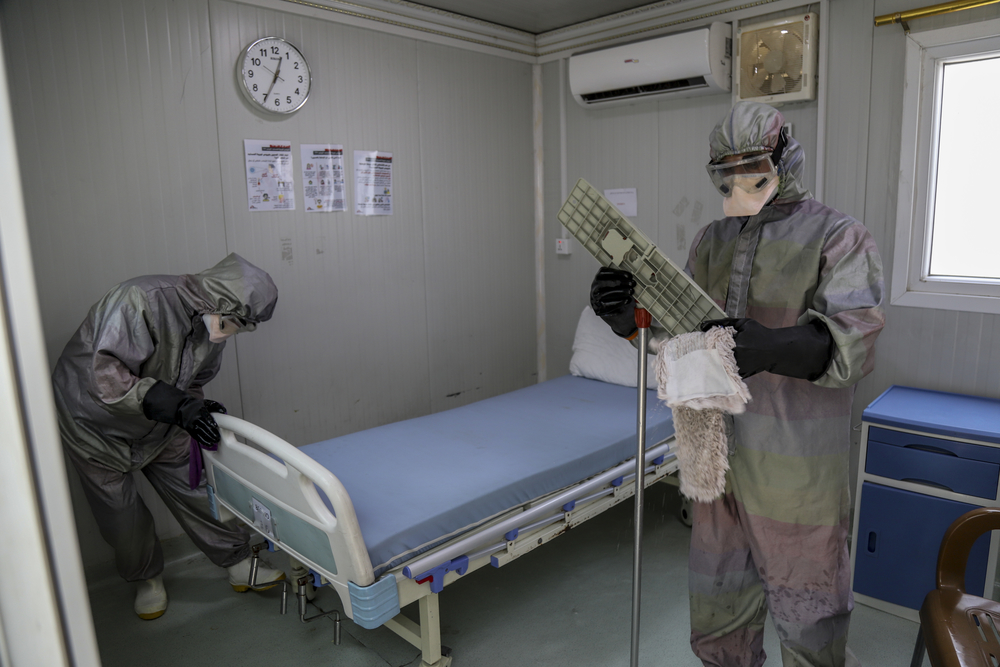

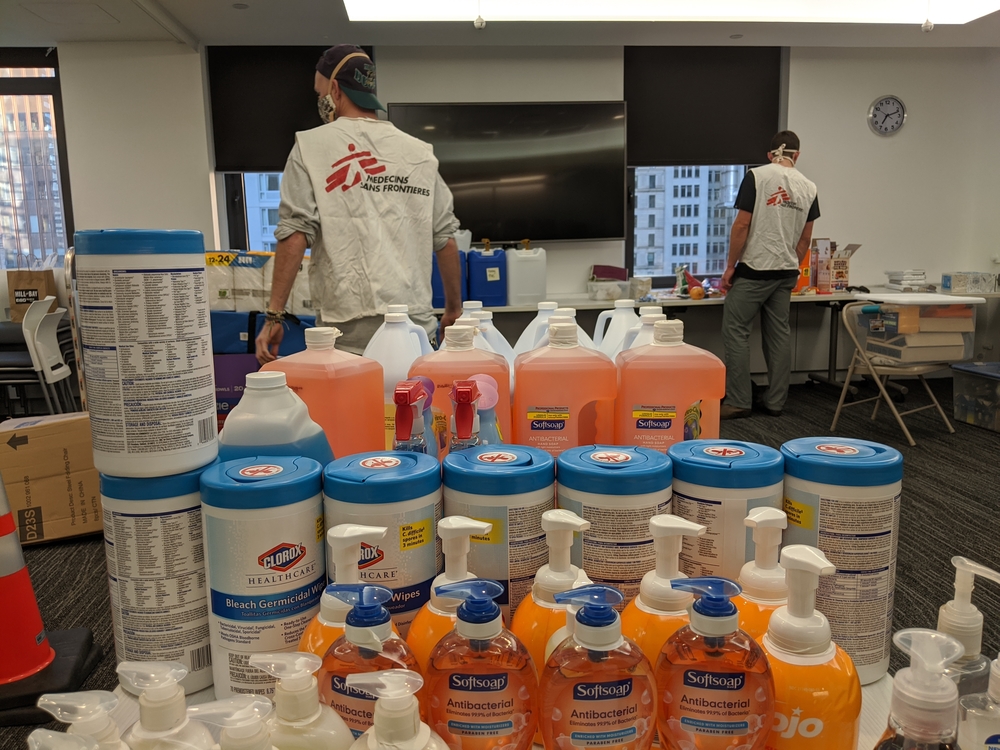

After the Palestinian Prime Minister announced the full lockdown in the West Bank, MSF teams have had to adapt their activities to protect patients and staff from COVID-19. Group mental health sessions and face-to-face consultations have been suspended, but patients continue to receive psychological support by phone.

Adjustment disorders are stress-related conditions that occur in response to a stressful or unexpected event, and the stress causes significant behavioural problems. Because people with an adjustment disorder/stress response syndrome often have some of the symptoms of clinical depression, such as tearfulness, feelings of hopelessness, and loss of interest in work or activities, adjustment disorder is sometimes informally called “situational depression.”