COVID-19: Five challenges in Bangladesh and the Rohingya refugee camps

One of the most densely populated countries in the world, Bangladesh also houses the world’s largest refugee camp. Across Cox´s Bazar, nearly one million Rohingya refugees live in overcrowded, unsanitary conditions. As COVID-19 spreads through Bangladesh, these are the five key challenges to overcome.

Highly vulnerable populations

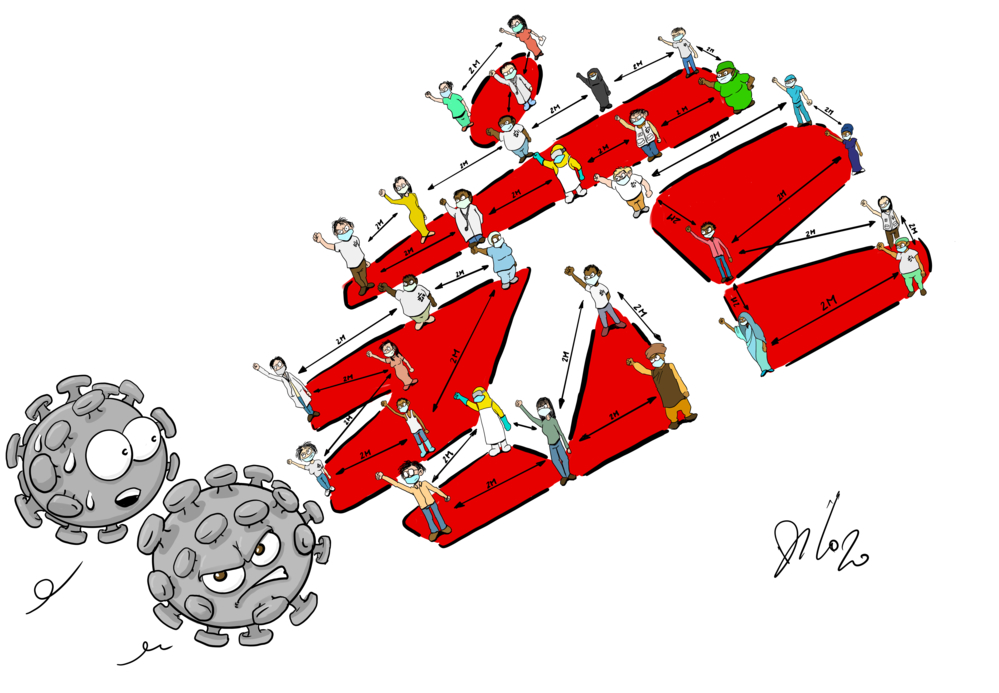

Across Bangladesh, many impoverished communities face a precarious existence in crowded environments, making them particularly vulnerable to COVID-19. Many Bangladeshis live in densely populated urban and slum areas and Rohingya refugees are stuck in cramped, squalid shelters, with up to 10 family members to a room.

Maintaining physical distance in these settings is near impossible. In the refugee camps, around 860,000 Rohingya live in just 26 square kilometres of land in Cox’s Bazar, with poor access to soap or clean water. They depend on communal distributions for drinking water, food and fuel, which means they must wait for hours in large groups to receive these.

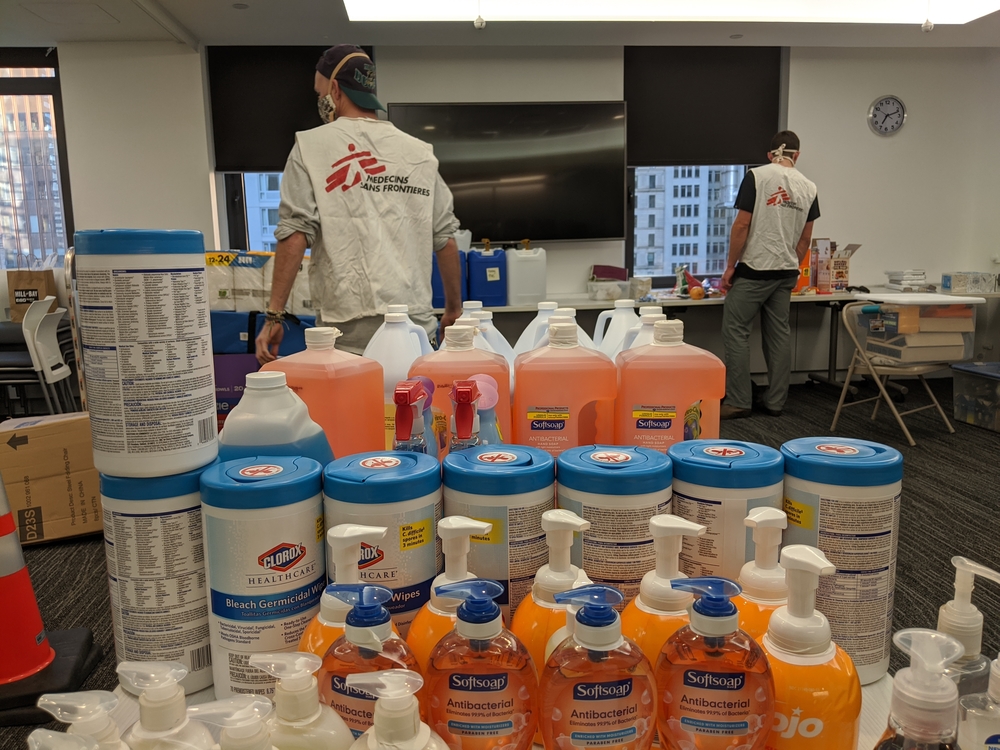

“People feel frustrated with the constant advice to wash their hands. If you have only 11 litres per day, how is this enough to wash your hands all the time?” says Richard Galpin, Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) water and sanitation expert.

After decades of persecution in Myanmar, during which access to healthcare was severely restricted, the Rohingya have low levels of health and lack the protection of routine immunizations, making them particularly vulnerable to infectious diseases.

Before COVID-19, around 30 percent of patients treated by MSF in the refugee camps presented with respiratory tract symptoms, such as shortness of breath. This puts them in a high-risk group for this new disease.

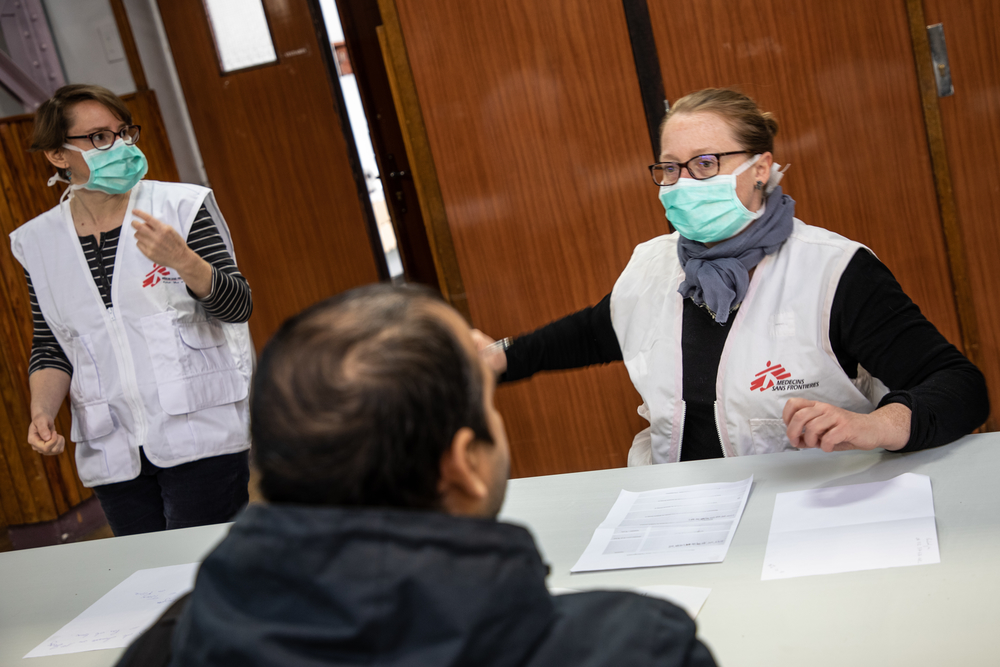

Maintaining essential services and access to assistance

Capacity within the health service is being redirected to deal with the spread of the coronavirus, and the humanitarian response has been significantly reduced. However, mothers will continue to give birth, children will get sick with diarrhea and chronic patients will continue to need medication. It is crucial that these essential, life-saving activities are maintained.

Travel restrictions, though key to limiting the spread of COVID-19, are affecting access to healthcare. It is much harder for people with ‘invisible’ illnesses to prove they are sick and eligible to travel to facilities for treatment. Those suffering from psychiatric disorders or non-communicable diseases, such as diabetes, might appear healthy, but if their regular treatments are interrupted, they risk regression and reappearance of very harmful symptoms. In the last week, one patient arrived at an MSF facility in tears. She was afraid she’d be turned away; it had taken her five days to arrange transport to come to the hospital.

For the Rohingya, the onset of the heavy monsoon rains in the coming month means the risk of outbreaks of water-borne diseases, such as cholera, will escalate. Keeping the water and sanitation infrastructure running for such a large camp population is an even greater challenge within the current restrictions. Latrines need to be cleared of sludge, and water networks maintained and repaired; all of which requires supplies, materials and manpower, which are all now in limited supply.

Erosion of trust

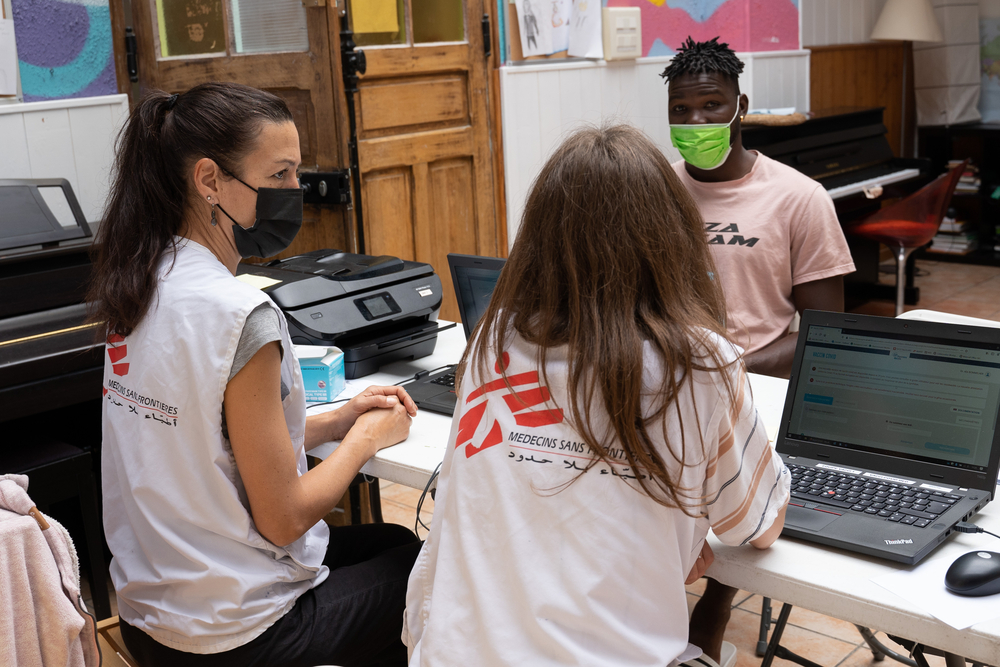

Through our experiences of providing healthcare during other infectious disease outbreaks, MSF has learned how crucial it is to involve and educate the communities we are there to help. This is vital to ensure they understand how to protect themselves, to tackle rumours and reduce fear, and to give people a sense of control. Bangladeshi and Rohingya communities are understandably frightened. Rumours and misinformation can spread as fast as the virus.

Fear is keeping people in need of essential non-COVID-19 treatment away from our clinics. Over the last few weeks, we have seen a stark decline in consultations. At the Kutupalong field hospital, in Cox’s Bazar, MSF normally sees between 80 and 100 patients for wound dressings every day. Many of these are chronic wounds, which need regular cleaning and dressing every two or three days. This has dropped to around 30 patients a day. Without these wound dressings, there is a risk of infections, sepsis and even death.

Our outreach teams in the camps and the neighbouring Bangladeshi villages are working to share advice on how to prevent the spread of COVID-19. To avoid gathering people in groups, they go house-to-house, speaking with individual family members.

We have made short videos for people to share over bluetooth, given the internet restrictions. We are also working with community and religious leaders to help share health messages by word of mouth, and organizing tours of our isolation facilities to build trust with the communities.

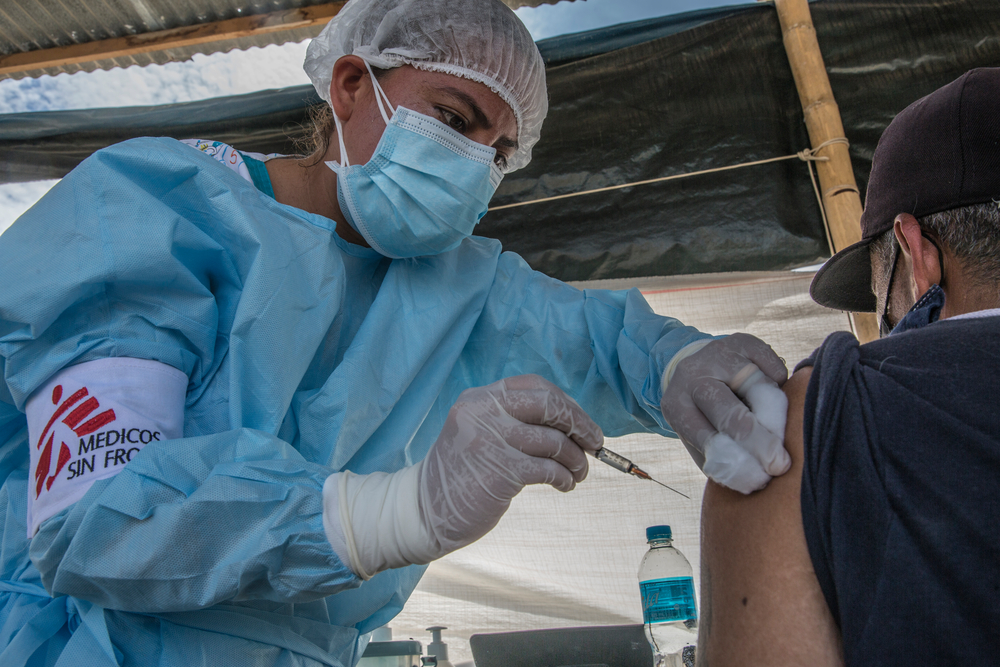

Protecting frontline workers

Healthcare workers are on the frontline of the COVID-19 response. Without them, there is no way to combat this impending health crisis or to address other medical needs.

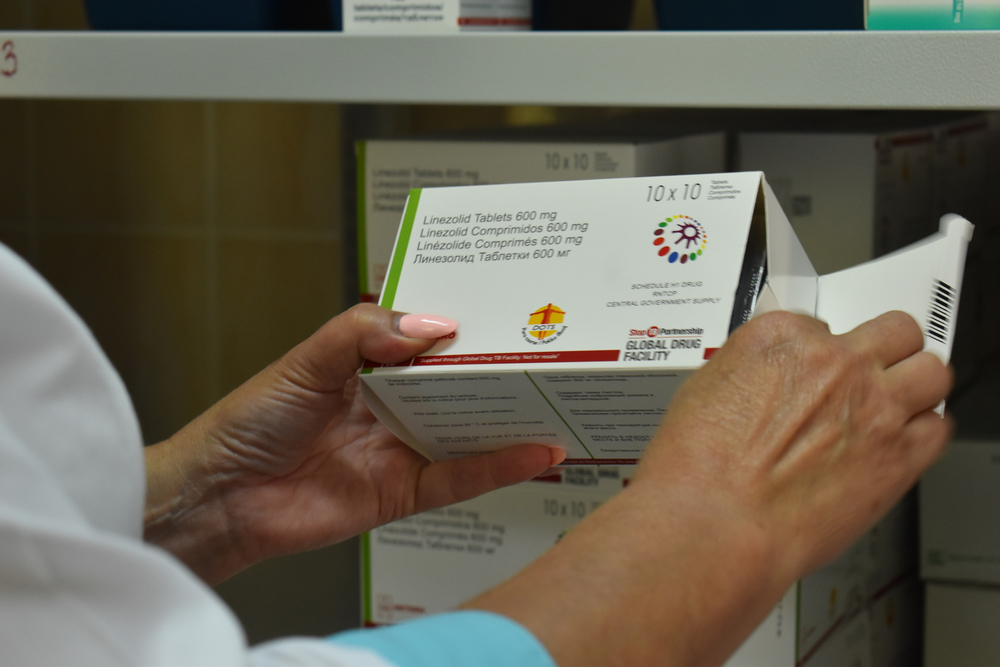

In Bangladesh, as elsewhere in the world, MSF is facing shortages of essential personal protective equipment (PPE), such as masks, gowns, goggles and gloves. Healthcare workers are the group most at risk of contracting COVID-19. MSF will not expose any of our staff to unnecessary risks of infection, but this will affect the work we can do.

“The limitations will determine our ability to respond to the COVID-19 outbreak, as well as our capacity to maintain ordinary medical activities,” says Muriel Boursier, MSF Head of Mission. “This uncertainty and having no guarantee that we’ll be able to keep our commitment to our patients, is a huge pressure on the team.”

While we have witnessed inspiring displays of solidarity with frontline workers across the world, we have also seen fear driving stigmatising and cruel behaviour. Bangladesh has not been exempt of these situations. Some of our staff have received verbal abuse or threats by communities fearful of COVID-19 and others are facing eviction by landlords unwilling to house frontline staff.

If healthcare workers feel unsafe or unsupported to do their jobs, there cannot be any serious response to COVID-19.

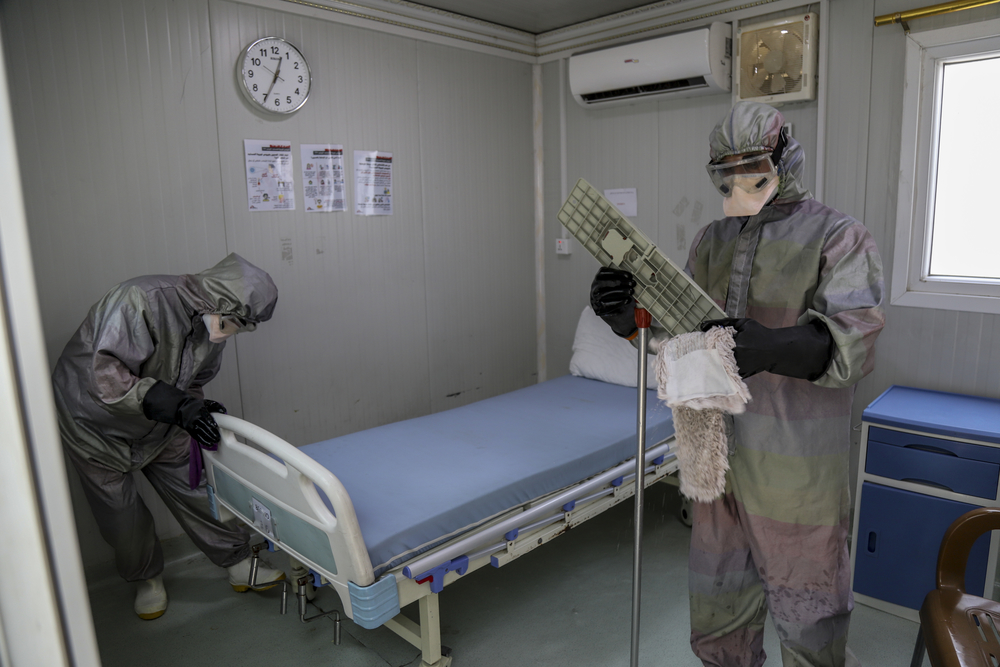

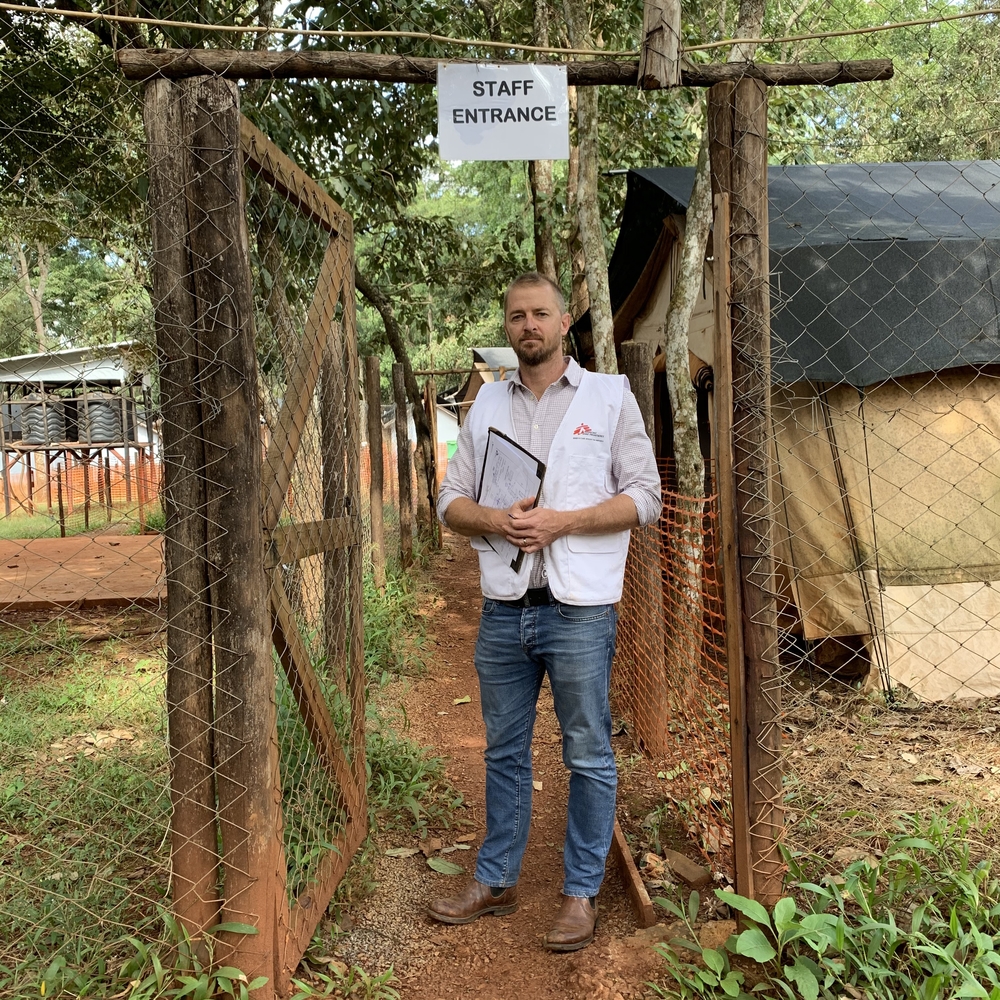

Managing COVID-19 patients

MSF has created isolation wards in all our medical facilities in Cox’s Bazar and is preparing two dedicated treatment centres. In total, we have made 300 isolation beds available, but this is just a fraction of the capacity necessary if there is widespread outbreak within the Rohingya community. Our clinics in the refugee camps are not able to treat severe cases given the lack of ventilators and limited availability of concentrated oxygen.

Increasing our response in this pandemic has meant a massive recruitment effort of local Bangladeshi staff. We also need international expertise, but restrictions on travel into Bangladesh mean that around a third of our international staff meant to be deployed in this crisis are currently stuck outside the country, severely stretching our capacity.

The need for medical staff, such as doctors and nurses, is clear, but there are many other people involved. We require managers to run our hospitals, logisticians to ensure we have quality medical supplies when we need them, and many more besides. MSF has hired a fleet of buses, which will shuttle hundreds of staff to MSF hospitals and clinics across Cox’s Bazar – a huge and time-consuming daily logistical exercise.

MSF is working round the clock despite these difficulties. To have a realistic chance at tackling COVID-19 amongst Bangladesh’s most vulnerable communities, all health actors and authorities must all work together hand in hand, in solidarity.