Northeast Syria: Hospitals run out of funds and medical supplies during second COVID-19 wave

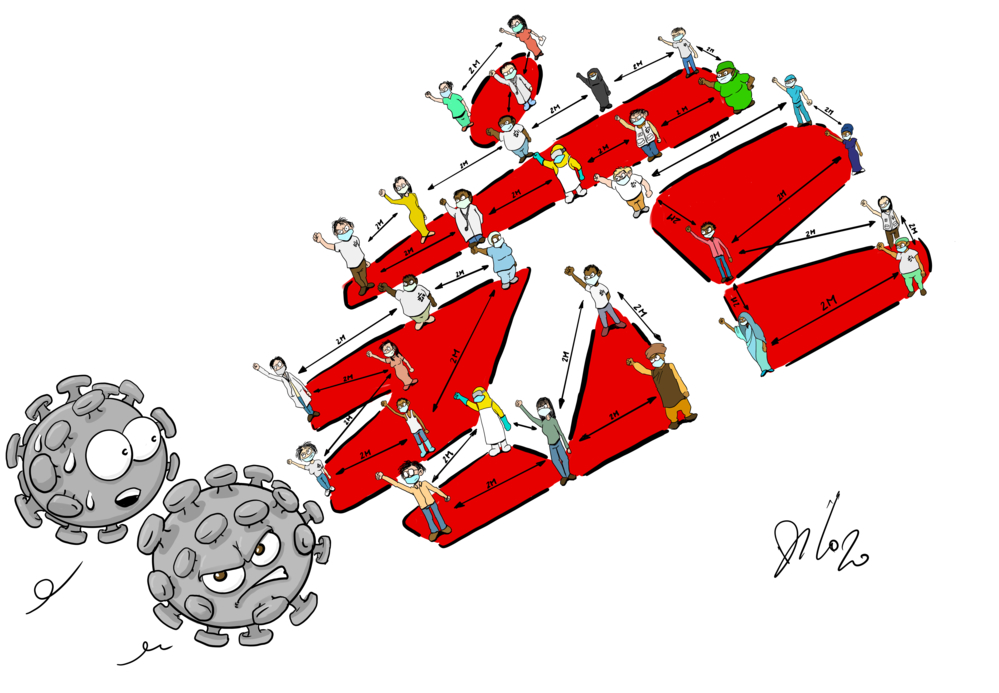

The second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic has reached Northeast Syria. As of April 26, there are over 15,000 confirmed cases – including at least 960 among health workers – and 640 deaths, reports international medical organization Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF).

The true numbers of people affected by COVID-19 is believed to be much higher than what is reported as people continue to struggle to access testing and healthcare. One year after the first case of coronavirus in the region, the response remains fragile and drastically underfunded, while plans for vaccinating frontline health workers and the population remain vague.

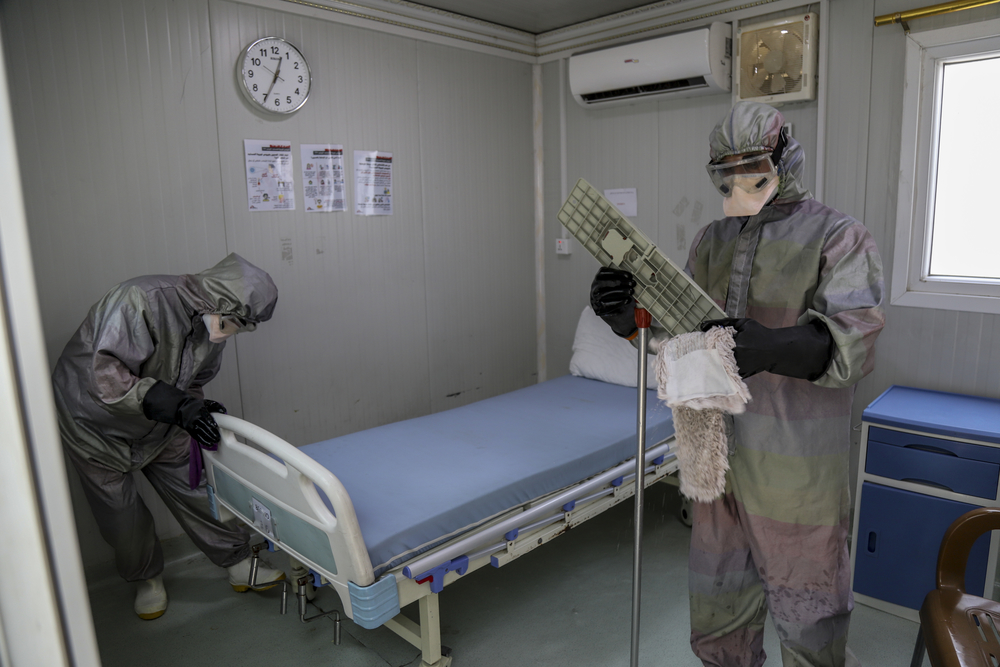

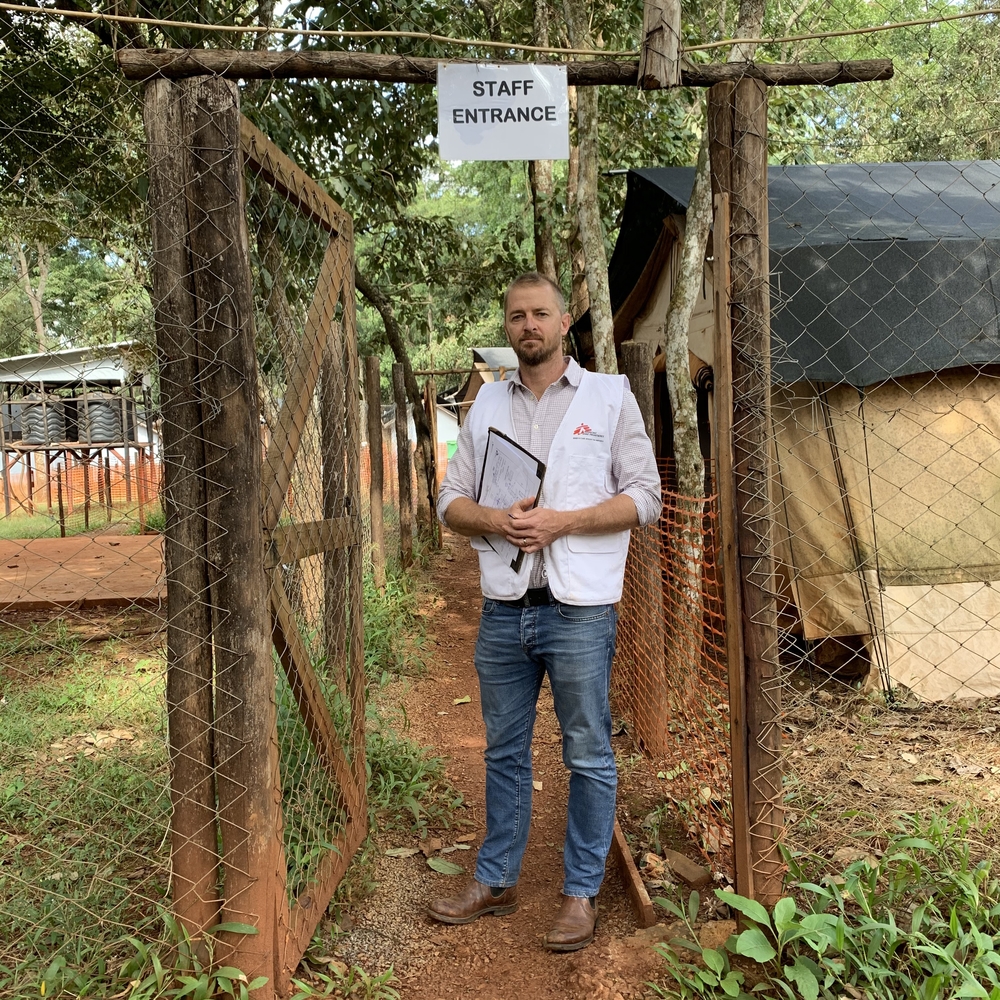

The current COVID-19 outbreak is spreading quickly through the whole of northeast Syria. In the two COVID-19 hospitals that MSF supports in the region, in Hassakeh and Raqqa, medical teams have seen a sharp increase in confirmed cases in the past month, including among health workers. With a PCR test positivity rate as high as 47% it is clear that many cases have gone unidentified which is directly linked to the limited testing capacity in the region.

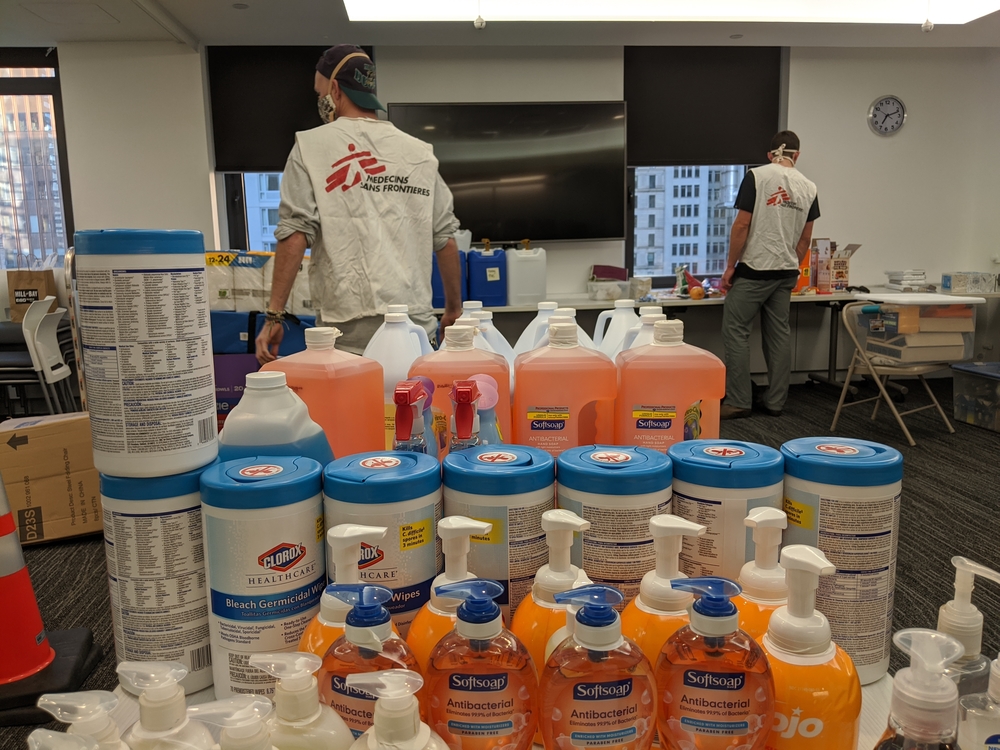

Lack of essential resources

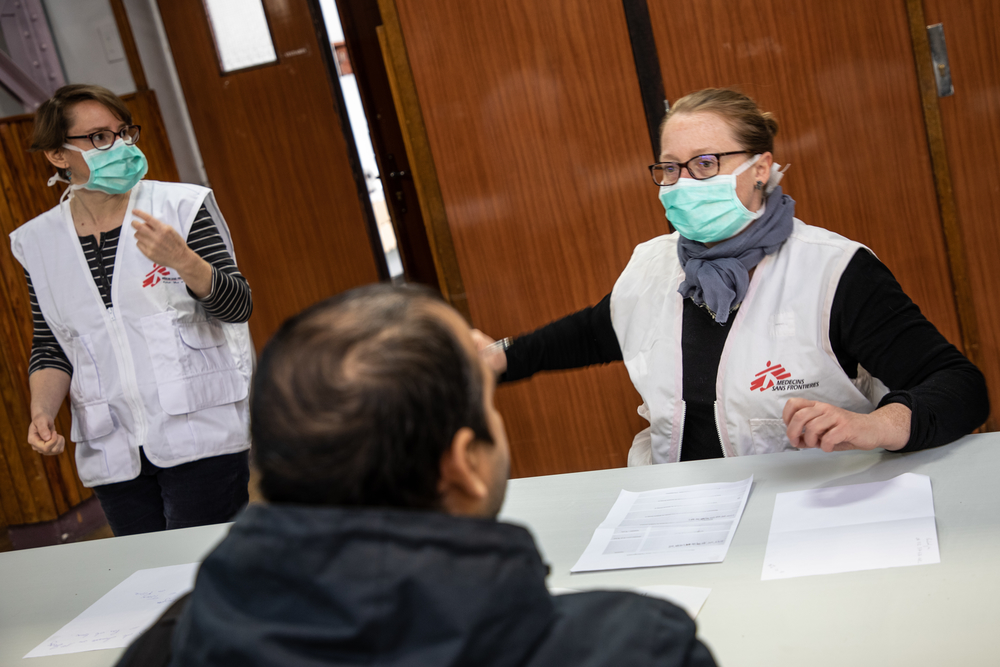

“It is shocking that after one year into the outbreak, the region of Northeast of Syria still struggles to find the essential COVID-19 supplies,” says MSF Medical Emergency Manager for Syria, Crystal Van Leeuwen. “There is a clear lack of laboratory testing, inadequate hospital capacity to manage patients, not enough oxygen to support those who need it most and limited availability of personal protective equipment (PPE) for health workers.”

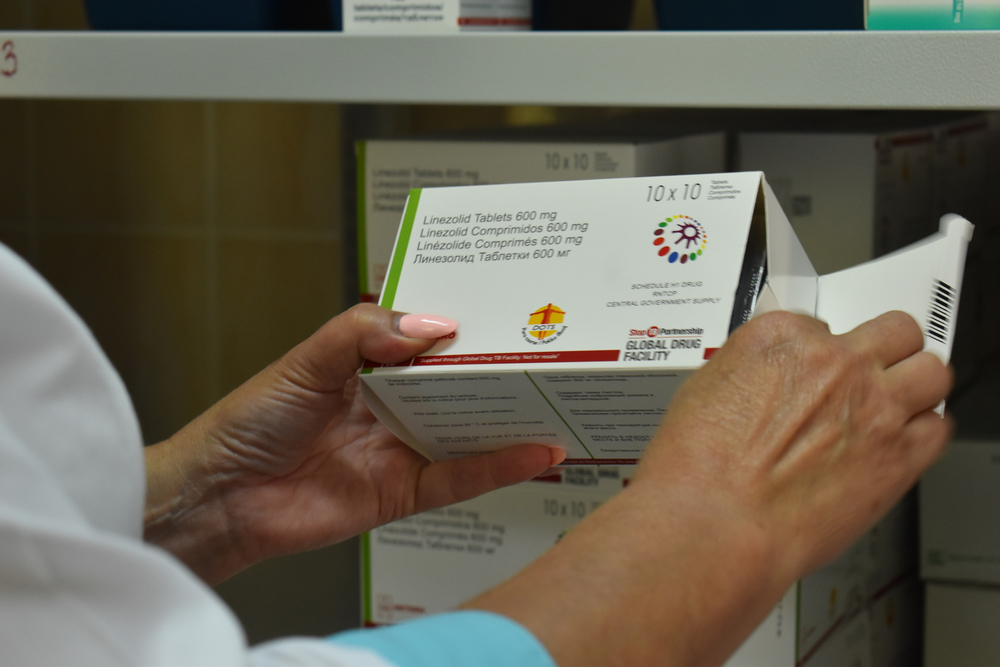

The only laboratory in the region that can test for COVID-19 is in Qamishli. It is currently experiencing critical shortages of supplies, and two weeks from now, there will be no PCR testing capacity in the region unless further supplies arrive. MSF has donated testing supplies to Qamishili laboratory on four occasions since the start of the pandemic to prevent imminent stock-outs and ensure continuity of PCR testing. “With no UN cross border mechanism in place for Northeast Syria creating challenges for supplies to reach the Northeast from Damascus-based organizations, such as the WHO, the region is woefully underserved in this outbreak”, says Van Leeuwen.

At least two COVID-19 treatment centres in Hassakeh and Raqqa have stopped activities after running out of funds and medical supplies, linked to lack of a long-term funding planning by the Humanitarian organizations and challenging in supply lines. While many other unsupported hospitals are raising alarms and requesting basic but essential support for items like oxygen, antibiotics and PPE to be able to cope with the increasing numbers of patients with COVID-19.

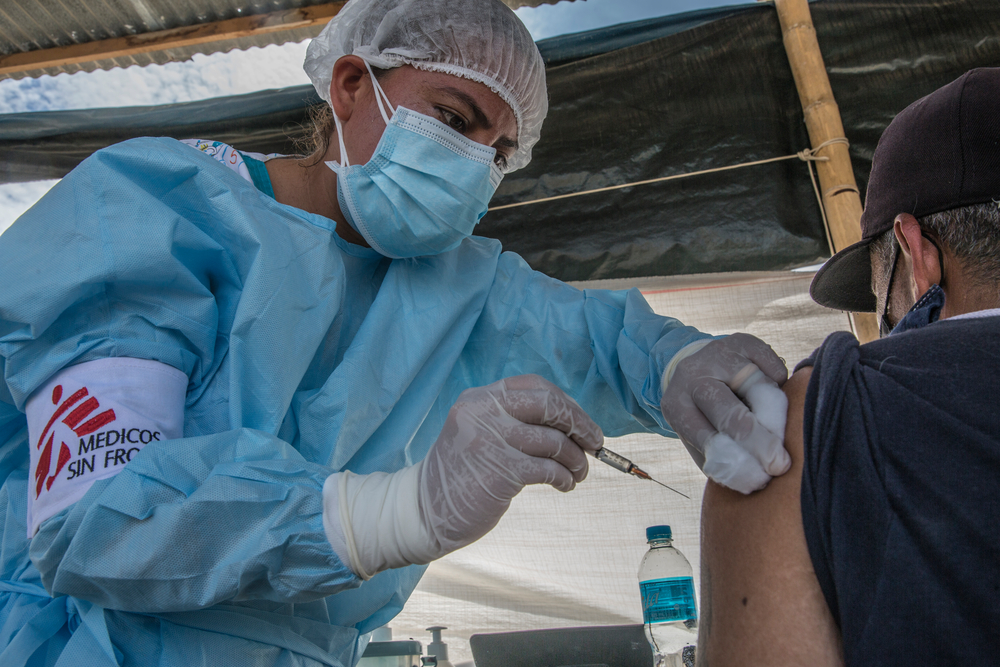

Vaccination plans falling between the cracks

While many frontline health workers across the globe have received their first injection to protect them against COVID-19, vaccination plans in northeast Syria have fallen between the cracks, with vague promises and insufficient planning. Local authorities report that they have been promised just 20,000 vaccines for an area that hosts five million people, and it remains unclear if those vaccines will even arrive.

“With these minimal commitments and lack of clear planning, we are seriously concerned that significant COVID-19 vaccination activities are unlikely to take place in the region anytime soon,” says Van Leeuwen. “The allocation of vaccine and other essential supplies has proven to be inequitable across the different regions of the country, showing that once again the humanitarian aid response in northeast Syria is being negatively impacted by regional politics and the lack of a UN cross-border mechanism.”

Many people in northeast Syria are already experiencing a limited access to health services, water and sanitation, making them especially vulnerable to this second wave of the pandemic. In the COVID-19 treatment facilities supported by MSF, the mortality rates continue to raise as the health services become more strained. With more than 70% of the patients admitted requiring oxygen, keeping up with the supply demands has not been possible.

“The COVID-19 response in northeast Syria is insufficient and people continue to unnecessarily die from this disease,” says Van Leeuwen. “A significant increase in assistance from health and humanitarian organizations is essential, as is flexibility from donors to support implementing organizations throughout the peaks and ebbs of this pandemic. With no foreseeable end to COVID-19 in Syria, vaccine provision and longer-term planning must be implemented in order to prevent further unnecessary suffering and to avoid sudden and disruptive shortages of essential supplies for COVID-19 prevention, testing and treatment.”