Paris, France: COVID-19 response must be accessible for most vulnerable

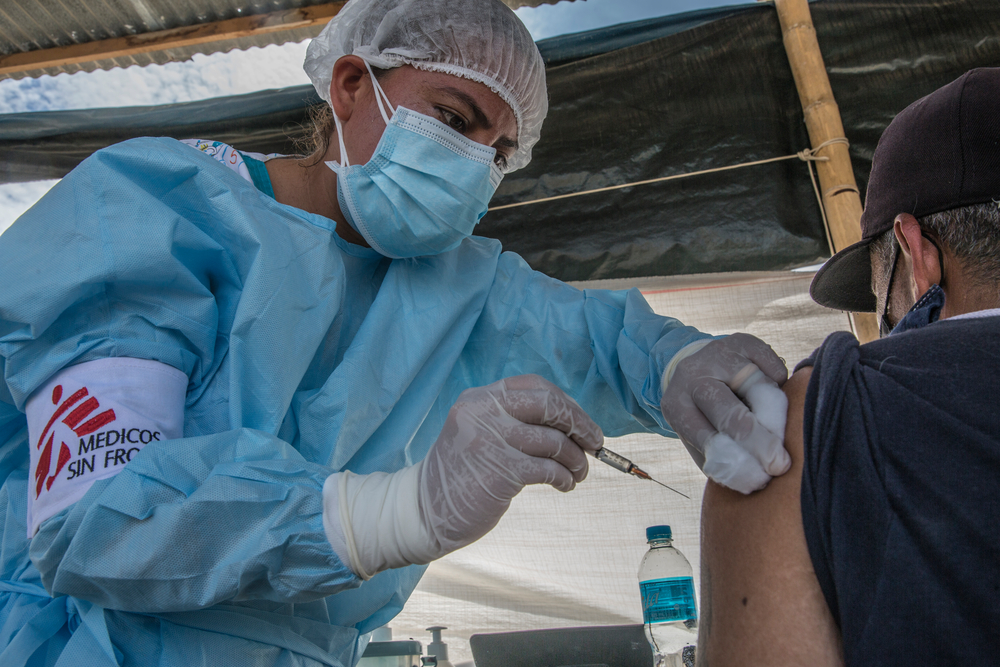

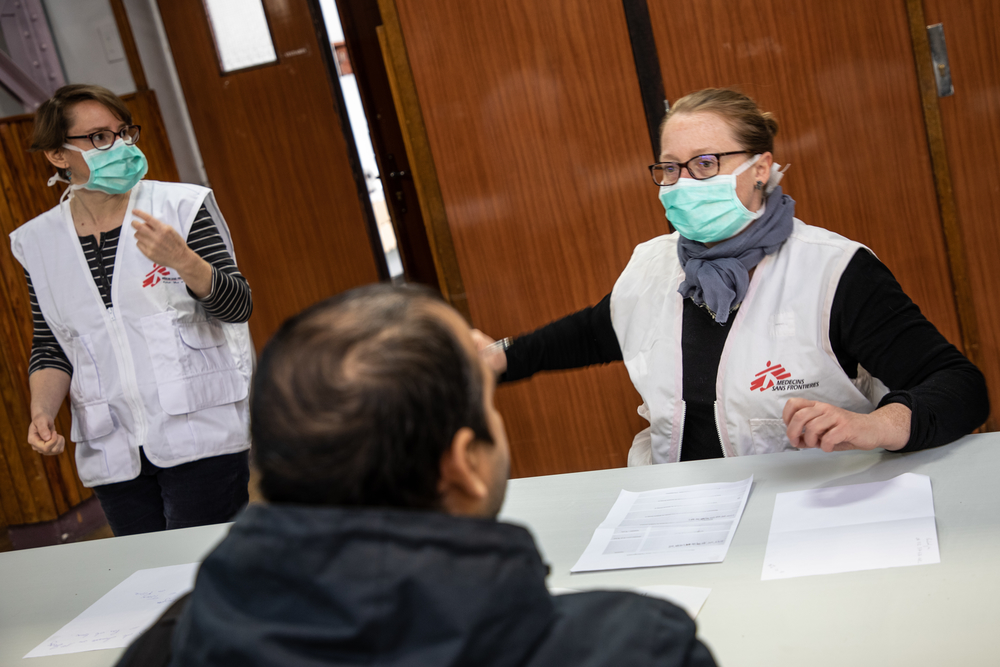

On March 24th, Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) began providing medical support to assist the health authorities with fighting the COVID-19 epidemic in Paris and the suburbs and also ensure access to routine medical care is maintained for people surviving on the streets in extremely precarious conditions. Annelise Coury is coordinating MSF’s response to COVID-19 in the region.

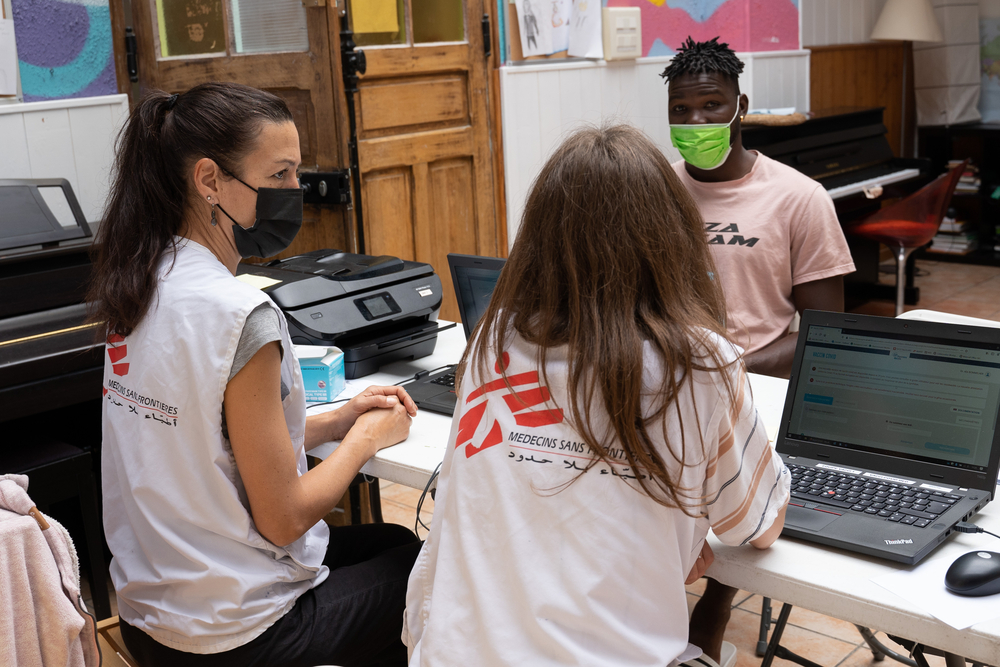

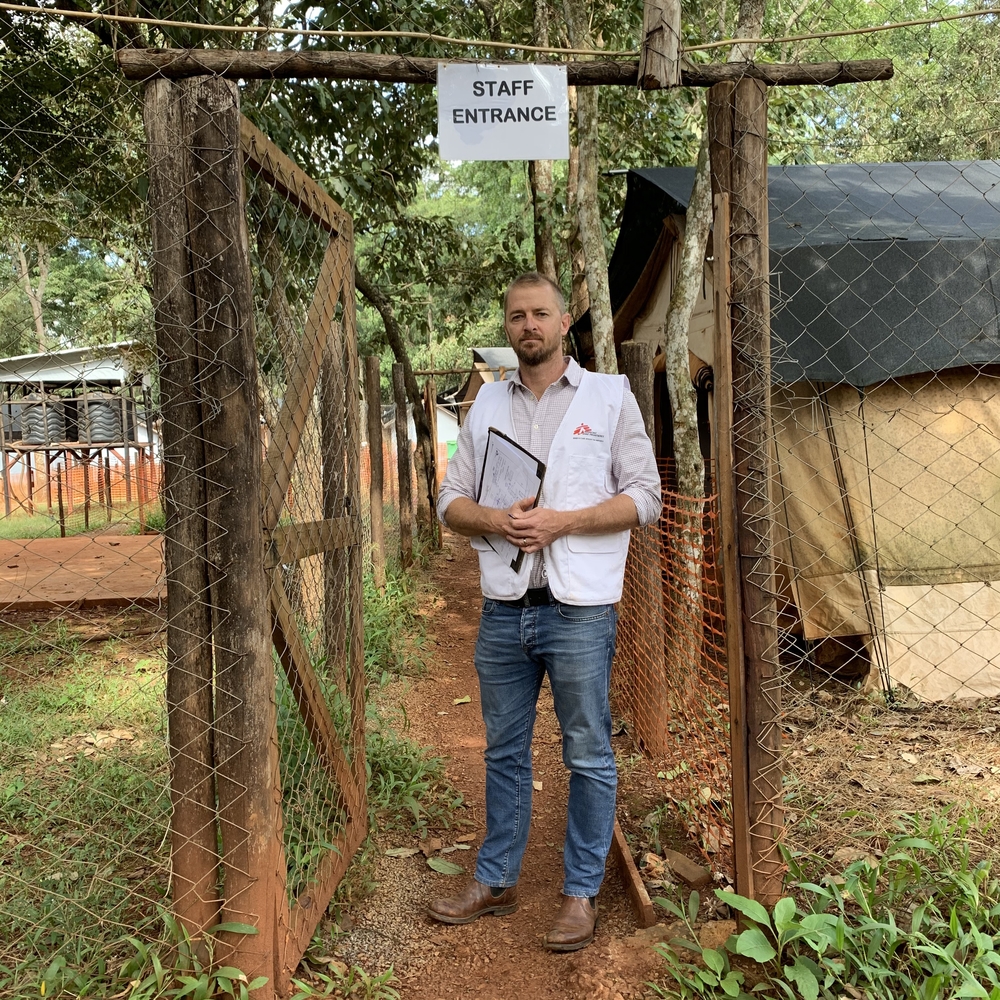

“We operate two systems to reach vulnerable people in Paris and the suburbs. Five days a week we set up a mobile clinic near food distribution sites so that a nurse and a doctor can give medical consultations to people living on the streets. Then we have teams of nurses going to places like, between others, the gymnasiums and hotels where the 700 or so migrants who, until March 24 lived in a camp in Aubervilliers, are being sheltered by the authorities.

Our objective is to identify anyone who could have symptoms of COVID-19. But, we also want to ensure routine medical care continues to be available to people who, since the lockdown, no longer have the support they normally receive from various associations.

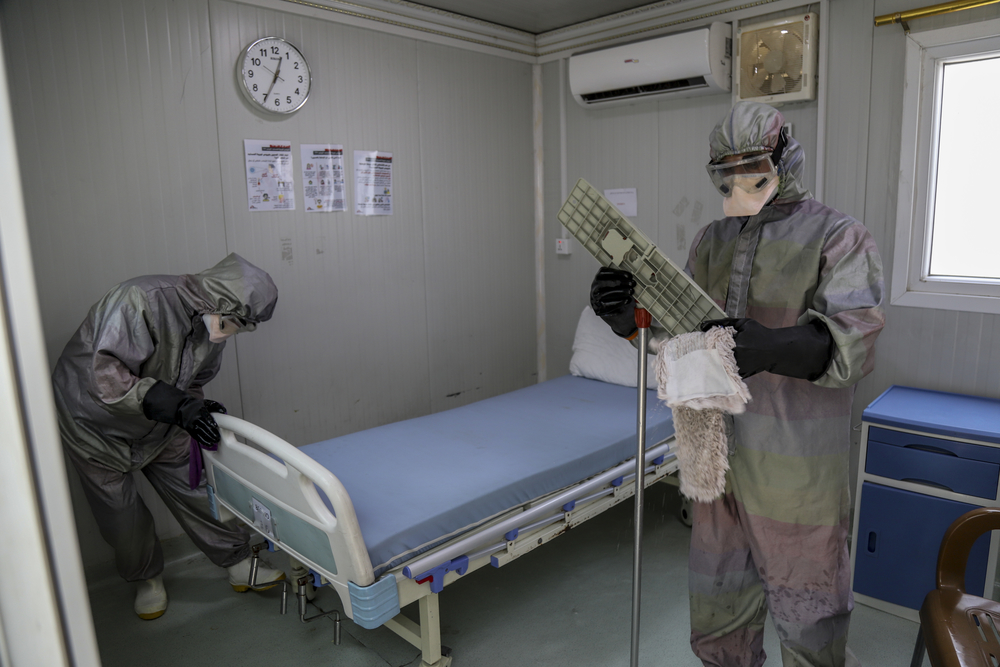

It’s unfortunate, but gymnasiums really aren’t the best solution. By their very nature, sports facilities are open spaces with no partitions. Often it’s simply not possible to isolate people suspected of being infected with coronavirus who should be accommodated in single rooms to enable social distancing. This is what MSF and many other organizations have been asking the authorities for.

In recent days, a hotline with nurses has been set up to receive support requests from various collective accommodation shelters, whether they are hostels for foreign workers, undocumented migrants, the homeless or others. They all have in common that they receive people in precarious situations in places where the containment and isolation of suspicious cases is not easy or even not feasible.

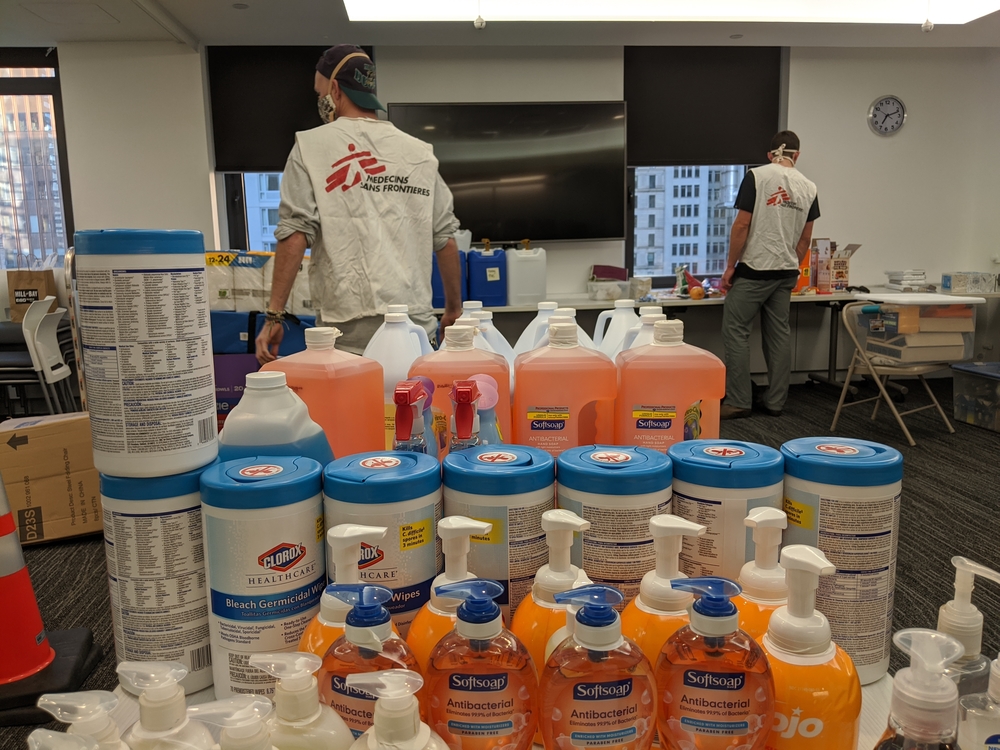

Along with delivering medical care, in all these shelters our mobile teams visit we want to protect their residents as well as their staff. We’re therefore trying to put basic hygiene measures in place to ensure the shelters don’t become new clusters of contamination.

We have homeless people coming to see us with problems not necessarily related to COVID-19. This is because the health centres they would normally go to are closed. Some have problems with their teeth, and others have skin disorders, small wounds or sores that must be attended to as they can be a real problem for people with no roof over their heads and no access to basic hygiene. Scabies is also an issue, especially in communal shelters where it can spread extremely fast.

As mental health services are also required, we have taken on a psychologist who joined the team. The epidemic and lockdown can increase anxiety in many people who, during the long journeys from their home countries, endured extreme trauma.

To make matters worse, many legal processes, e.g. asylum applications and appeals, are on hold. The negative psychological impact this causes is easy to understand. On top of all this, some migrants and people living in the street don’t have any more financial income.

All so many factors that are contributing to making people already fragile even more vulnerable. The lockdown and reduced access to medical care will inevitably affect the physical and mental health of people who have nowhere to go.”