COVID-19: Preparing in South-east Asia

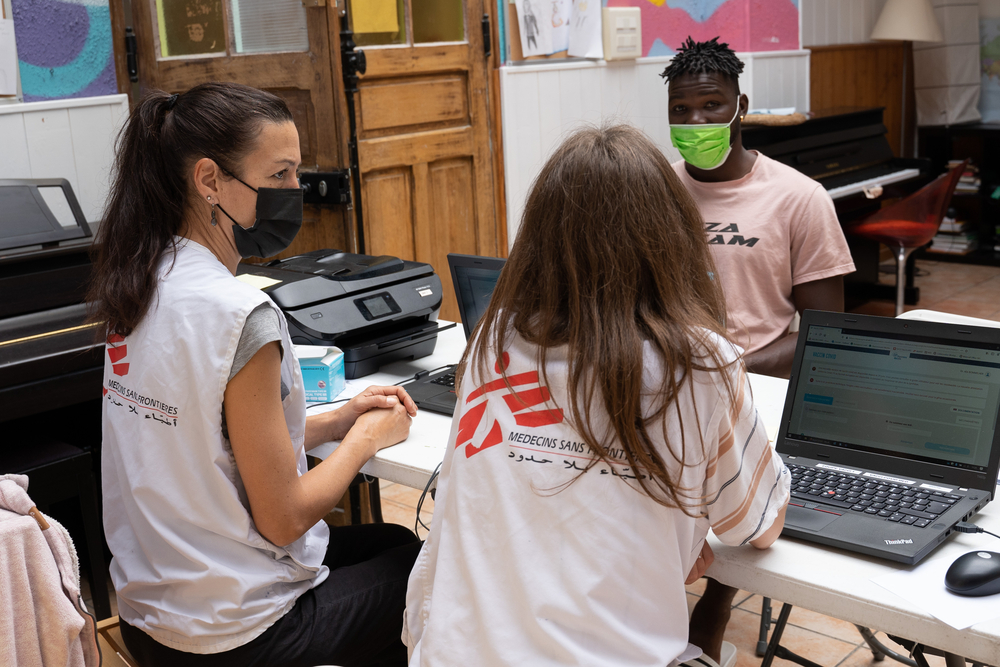

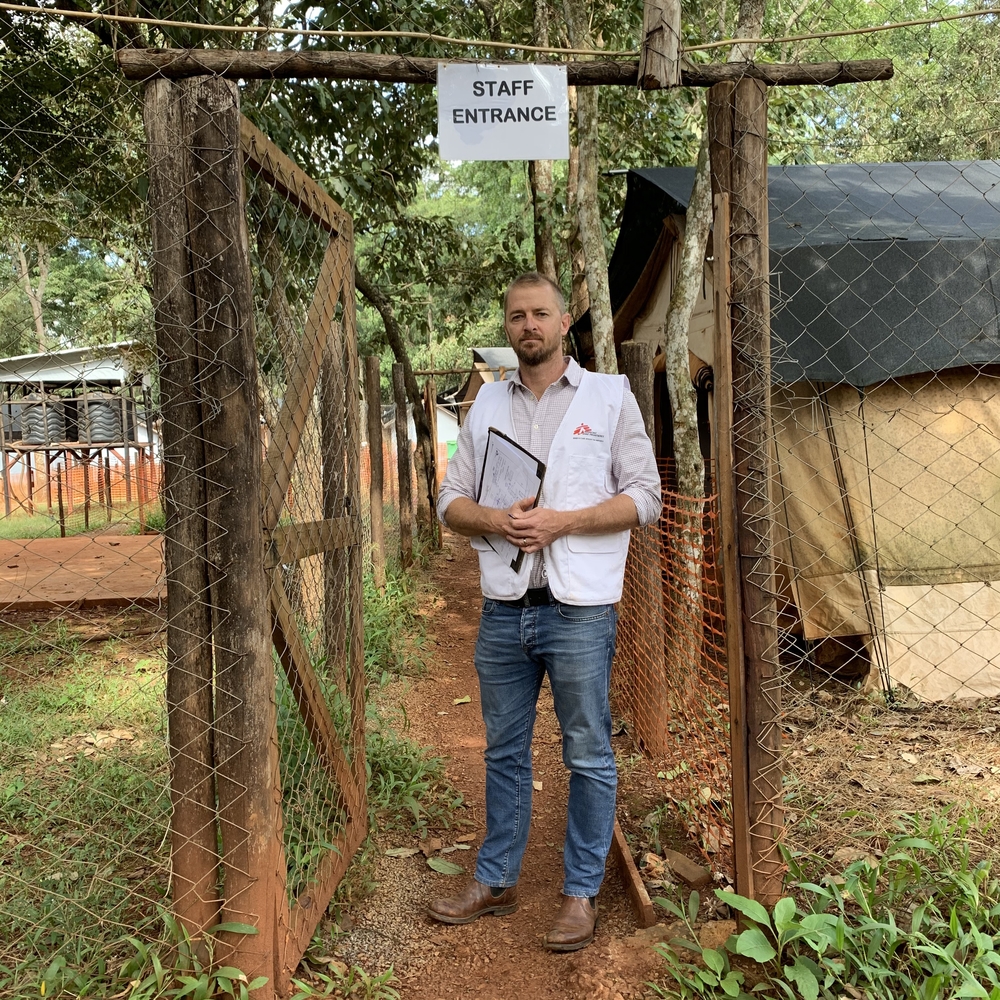

Tankred Stöbe, Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) emergency coordinator, visited several countries in South-East Asia to assess their preparedness for potential outbreaks of COVID-19 coronavirus and the support MSF could provide.

He participated in training sessions with healthcare staff in a hepatitis C clinic in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. A similar training was held in a hospital in Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea, where MSF treats patients with tuberculosis. The training sessions helped to improve knowledge and reduce fear among the staff, two prerequisites for providing the best level of care to our patients. Dr Stöbe describes the work he undertook in South-East Asia.

What did you do during your assessments?

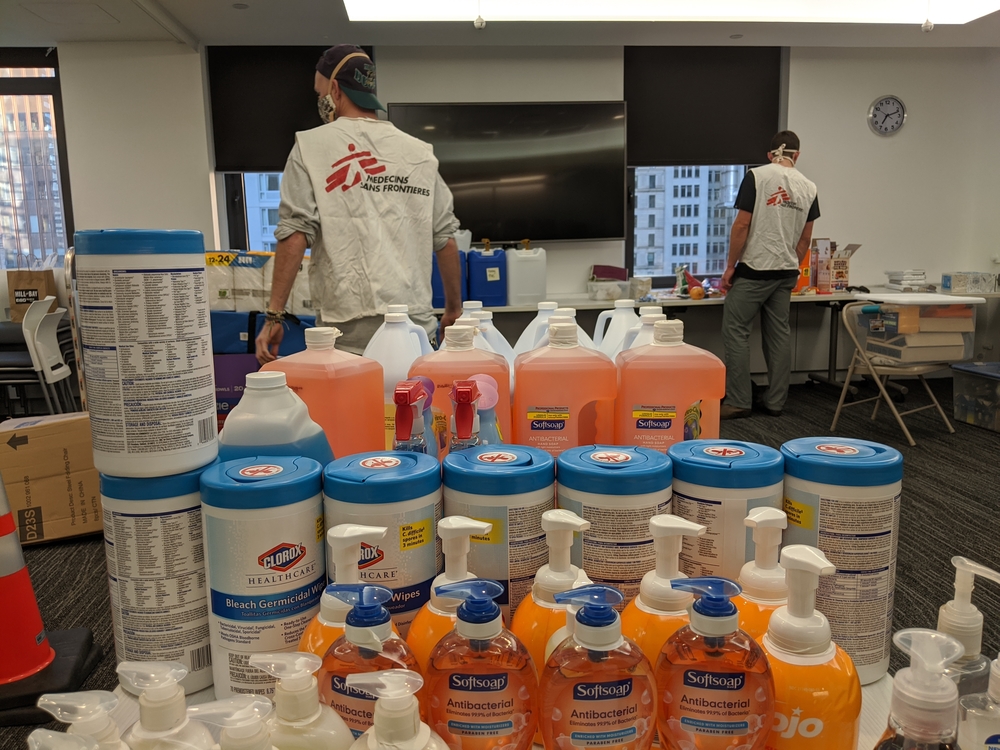

Some of the countries neighbouring China lack the robust medical infrastructure and effective systems to respond to emergencies like the current outbreak of COVID-19. We discussed contingency plans with hospital staff, including stocking the correct materials, and concrete step-by-step guidance for how to support patients and communities once cases of COVID-19 are diagnosed. Gathering evidence-based epidemiological information and appropriate training are an essential part of such preparations.

Why are countries with weak health systems particularly vulnerable in outbreaks?

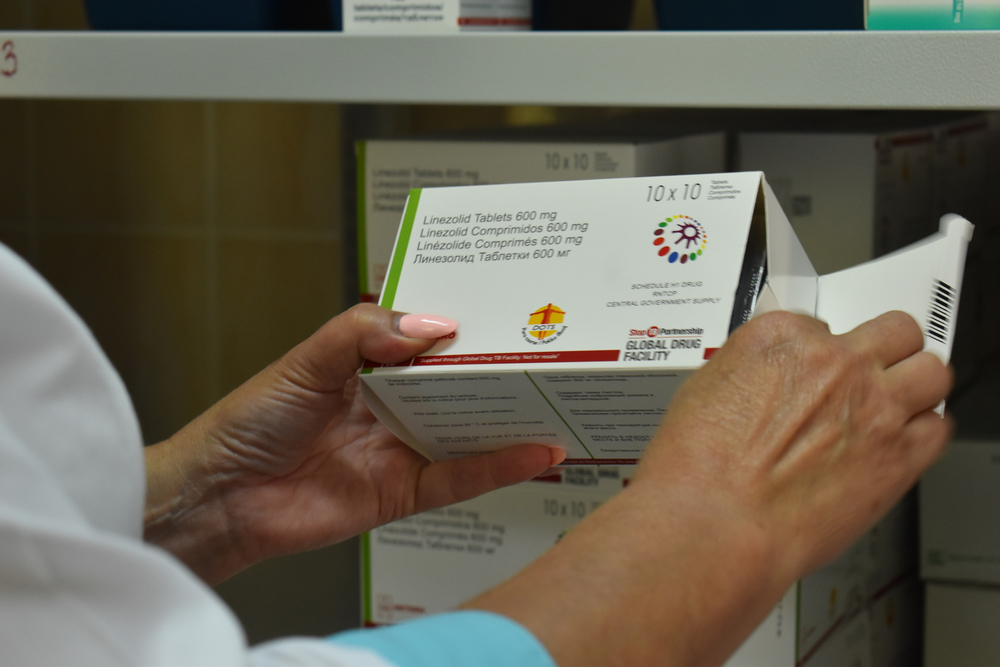

There are fewer doctors and nurses to take care of the population and they often have limited stocks of drugs and medical equipment. While they can cope with the daily medical challenges they face, they do not have the resources to respond to an additional crisis. In some places, the laboratories have limited capacity to carry out tests to confirm infections. However, in northern Laos, I was impressed to see how medical staff had developed strategies in case patients suspected of having COVID-19 arrive at their hospital, in spite of their limited resources. For the time being – with the border to China closed – it seems they can get by. It remains to be seen what will happen once the border crossings open again.

There are fewer doctors and nurses [in countries with weak health systems] to take care of the population and they often have limited stocks of drugs and medical equipment… they do not have the resources to respond to an additional crisis.

Dr. Tankred Stöbe | | Msf Emergency Coordinator

TWEET THIS:

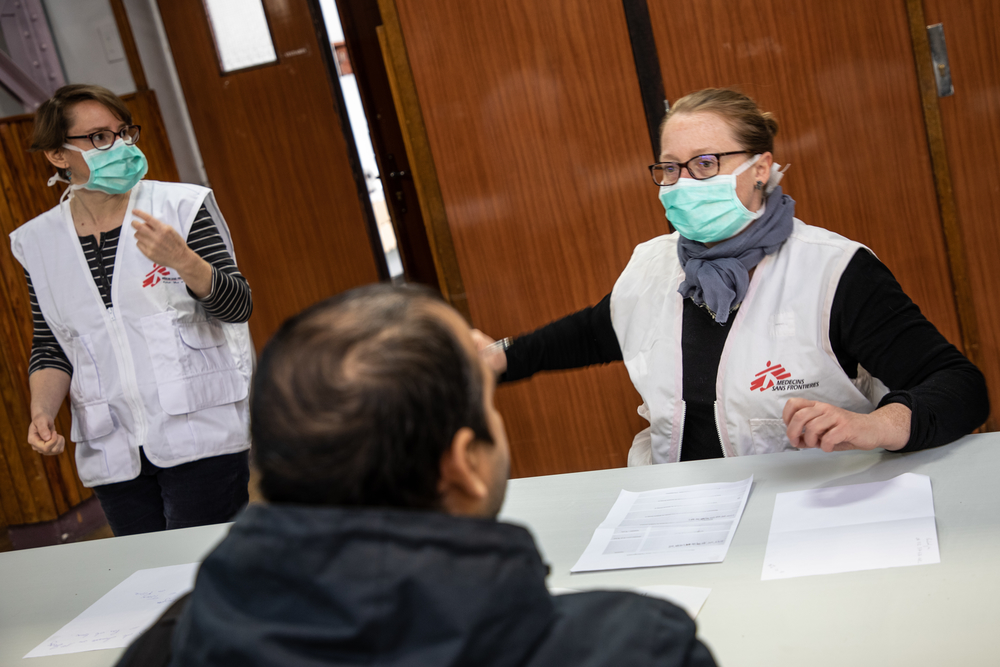

What questions were raised during the training in Phnom Penh?

A lot is still unknown about COVID-19, so we started by sharing relevant information about the virus, the ways in which the infection is spread and how to prevent this. Staff at the training in Phnom Penh posed many pressing questions and we answered as many as we could, but we were also open about the things that are not known at this time. The lack of available information on the new virus causes anxiety and fear even among hospital staff. It was important to remind them that in eight out of 10 cases patients only develop mild symptoms and the mortality is currently around three per cent.

Did you provide practical training as well?

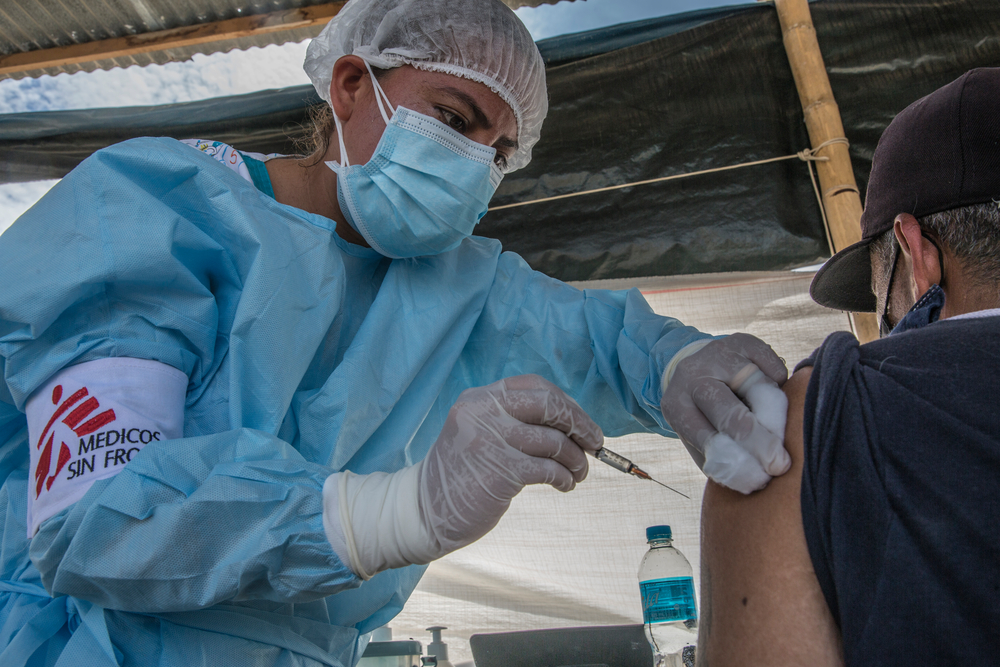

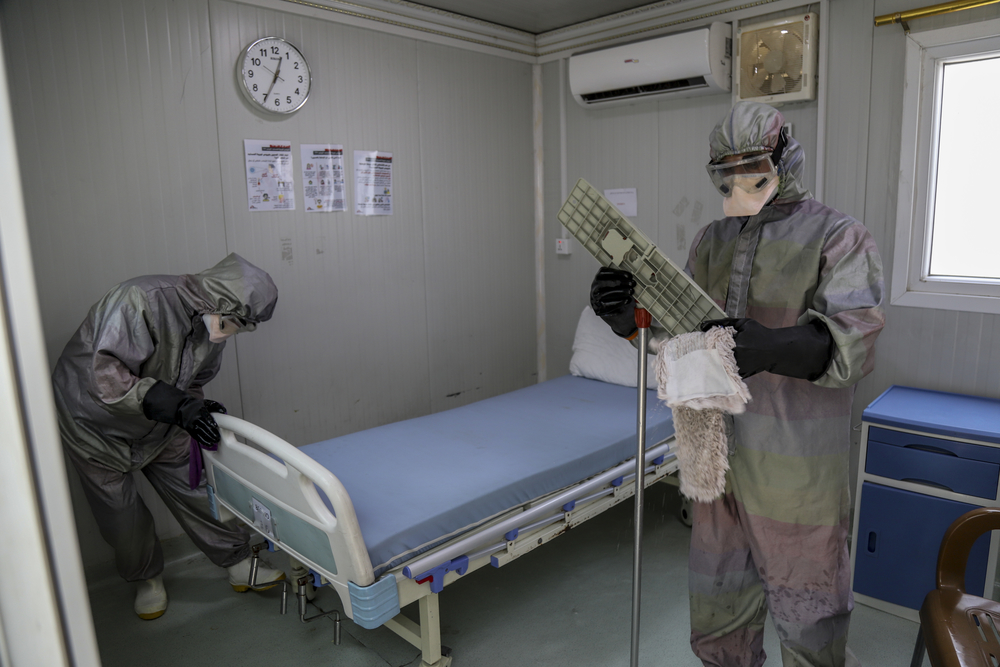

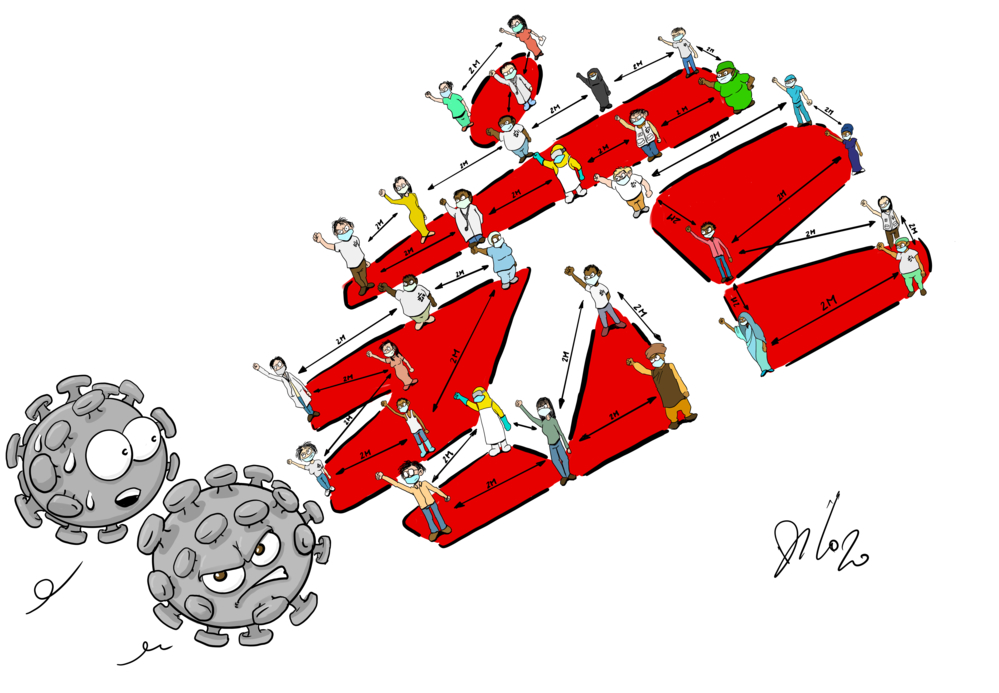

Yes. It is crucial to prepare hospital staff so that when the time comes they have the procedures in place that enable them to quickly and professionally handle patients showing symptoms of a suspected COVID-19 infection. At MSF, we focus on a step-by-step approach to providing systematic and practical guidance. This means we show how to put on personal protection equipment, how to set up a triage point, where suspected cases are separated from other patients, and how these cases should be treated. This is what matters in the end: doctors and nurses need to be equipped to provide the best possible care to patients in what might be a chaotic situation. Both in Cambodia and Papua New Guinea, this was highly appreciated.

What is MSF planning to do next?

This depends on different scenarios: as long as there are no cases of infected patients or only imported infections, we’re focusing on preparedness and checking we have all necessary equipment in place, identify reference laboratories and assess isolation and intensive care capacities. Once our teams start to see patients infected with COVID-19 in their country, they will help ensure that entry screenings are in place to isolate suspected cases; this helps to prevent the infection from spreading. In case of wider outbreaks, we will make sure to continue the care we provide to our current patients, and if necessary and feasible, to support the country’s public health infrastructure.