MSF wants Trudeau to commit to fair access to COVID-19 vaccines

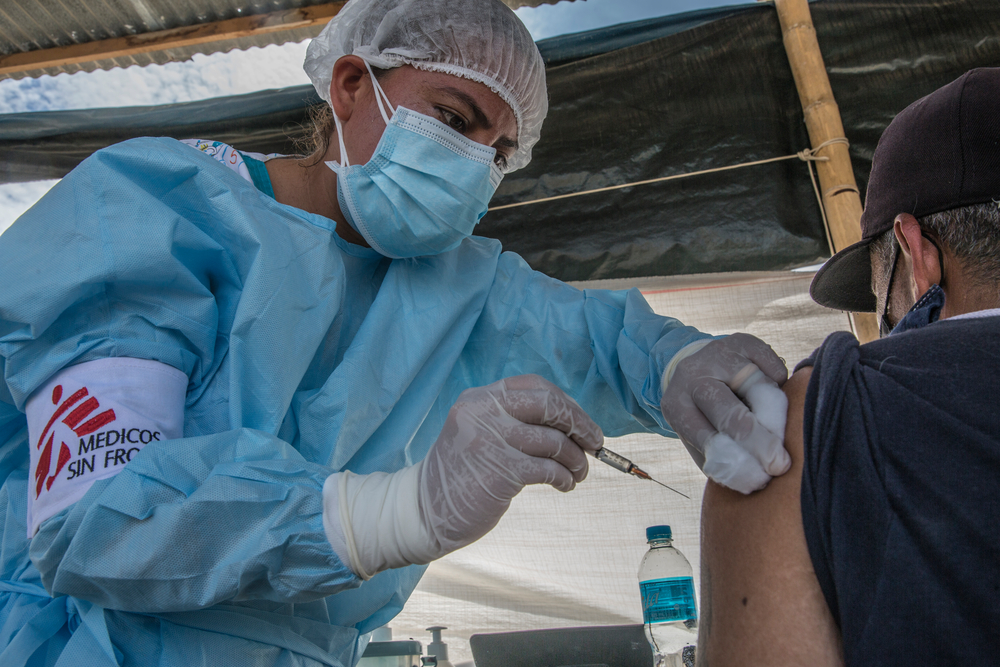

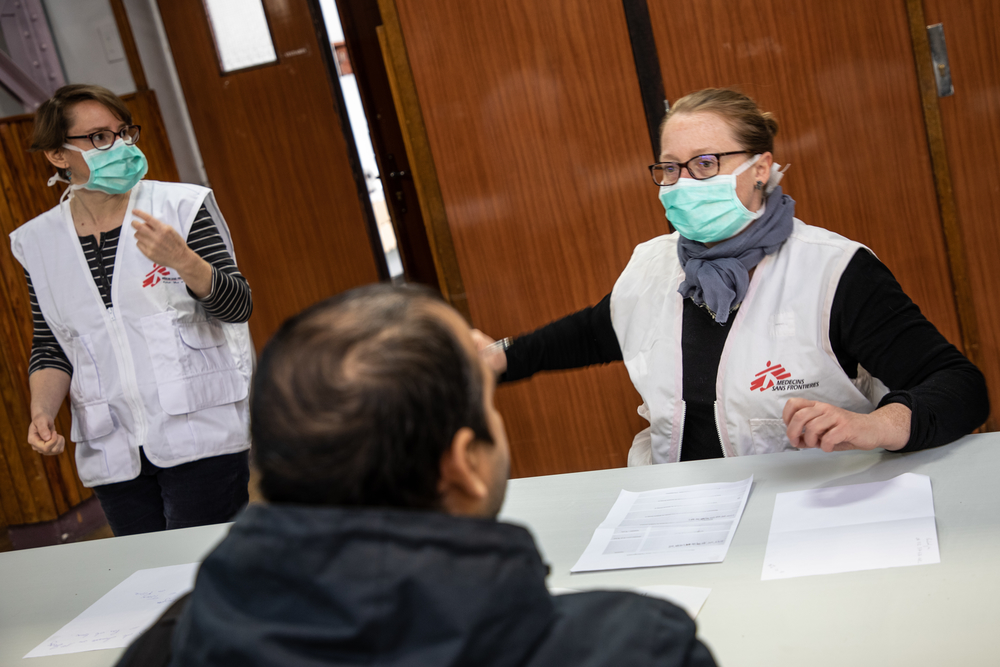

This interview with Jason Nickerson, Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) Humanitarian Affairs Advisor, originally appear in the Toronto Star.

The government of Canada is full of good intentions but in the global race to find a COVID-19 vaccine, Doctors Without Borders says that’s not good enough.

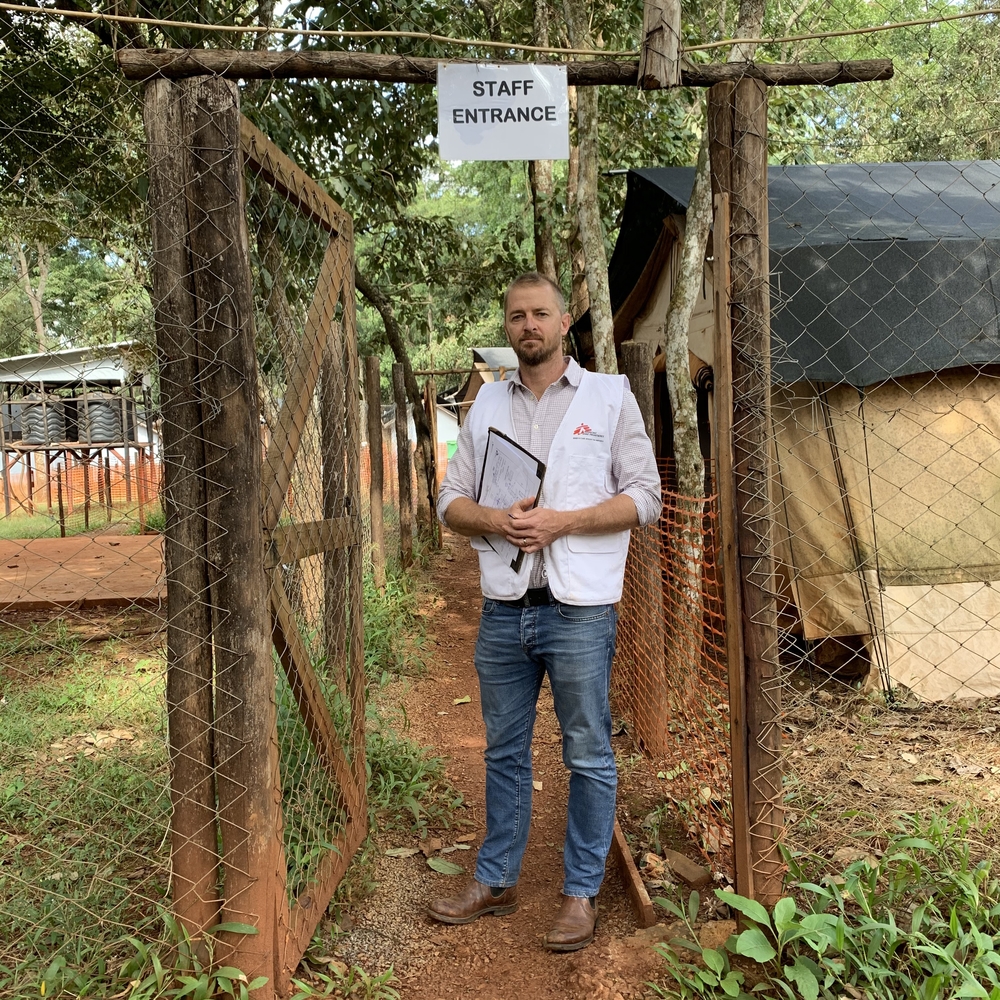

Dr. Jason Nickerson, a population health expert who’s worked in some of the world’s toughest hot spots, says the Canadian government needs to back up its words and Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s calling for global co-operation with action.

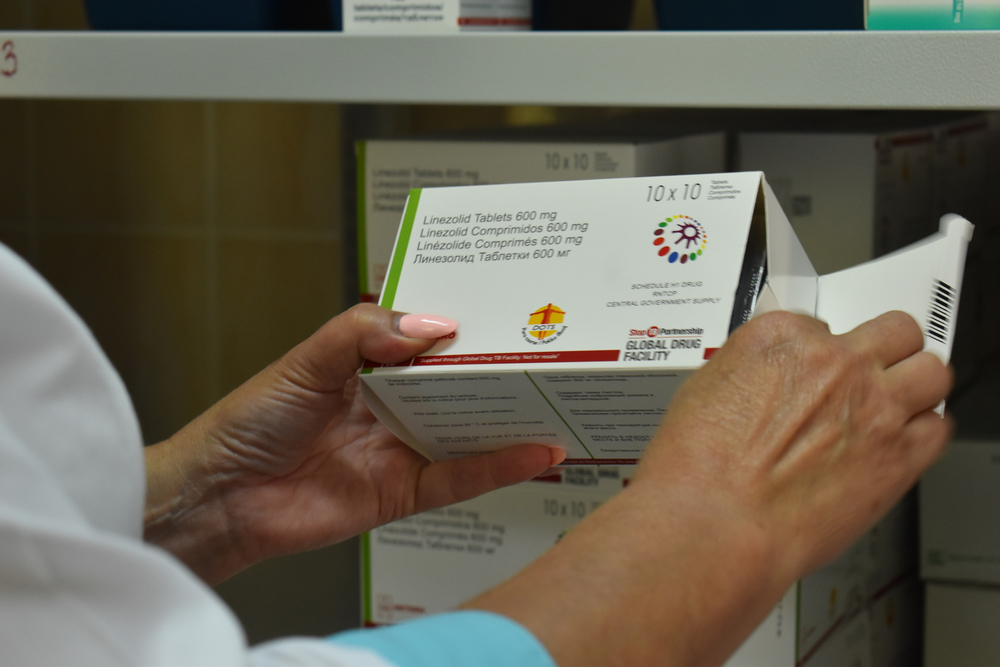

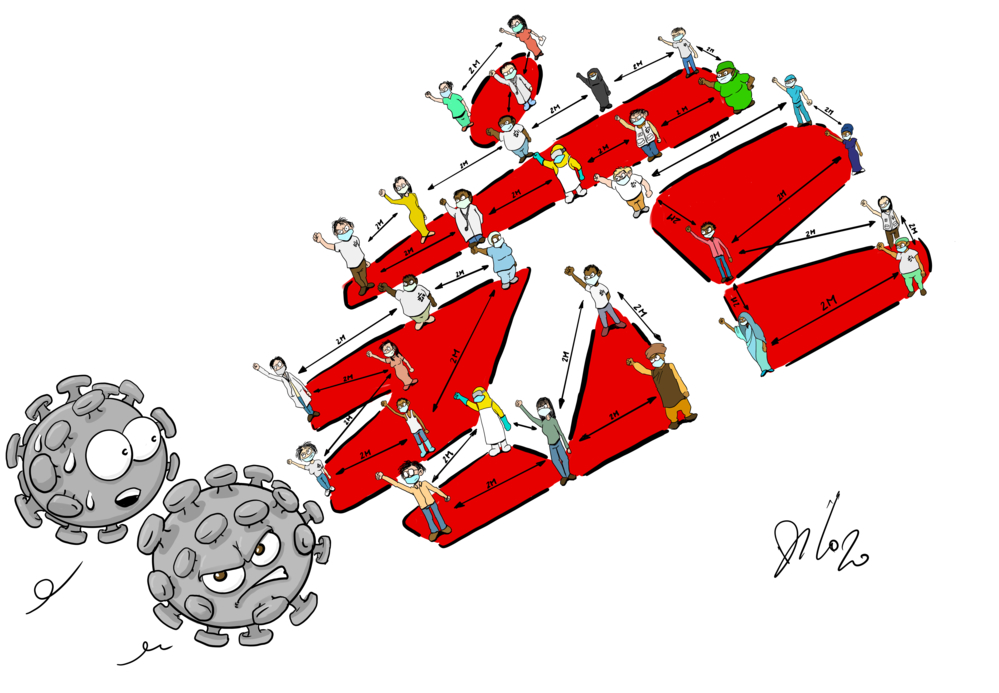

As researchers scramble to nail down a COVID-19 vaccine, MSF (the group goes by the French acronym for Médécins Sans Frontières) says public research money must be tied to guarantees that any research or vaccine funded by Canadian taxpayer dollars is made available to all, and at a fair price to the poorest of countries.

“Good intentions quite frankly just aren’t going to be good enough,” says Nickerson, who’s battled infectious disease outbreaks in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Haiti, Afghanistan and Sudan with MSF.

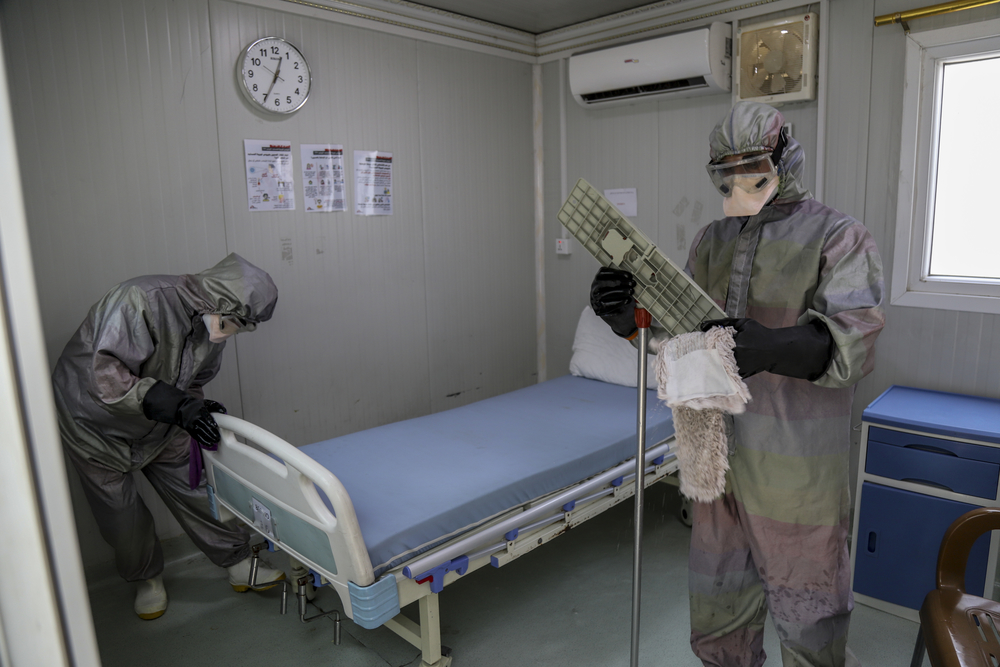

As of Wednesday, there were 183 vaccine candidates in various stages of development around the world, according to the Vaccine Centre at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. Just the day before, the World Health Organization had listed 136 vaccines on its tracker.

That’s how fast the science is moving.

Yet around the world, only about 15 potential vaccines are at the stage of human clinical trials, including one in which the National Research Council is collaborating with CanSino Biologics Inc. — a China-Canada company — on a vaccine soon to be tested in a large trial at Dalhousie University.

Research is also underway here into vaccine candidates in at least five Canadian locations including the University of Manitoba, VIDO-Intervac at the University of Saskatchewan, the University of Alberta, the University of Western Ontario, and CanSino is also working with Vancouver’s Precision NanoSystems on a separate vaccine candidate. All are at the preclinical trial stage.

Nickerson appealed to the Commons health committee this week to demand Ottawa finally enact recommendations MPs made two years ago to ensure “equitable access” to effective COVID-19 drugs and vaccines — once they are discovered.

Right now, there are no drugs or vaccines authorized to prevent, treat or cure the disease caused by the novel coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2.

Most experts like Dr. Jeff Kwong, interim director of the Center for Vaccine Preventable Disease and a professor at the University of Toronto’s Dalla School of Public Health, believe a vaccine will not be available in 2020, and possibly not until well into 2021.

But Kwong says there’s a high level of co-operation between pharmaceutical companies now, and he hopes it will not stop once a successful candidate is found.

“As long as companies are willing to share the intellectual property of how to make the vaccine, then I think we’re OK from a global perspective,” said Kwong. “I don’t know, but based on the fact the level of sharing so far has been unprecedented, maybe that will continue to be the case. Maybe I’m being naïve.”

Kwong is also optimistic, or at least hopeful, that Canada is in a good position whenever that happens.

“I think there’s definitely a possibility that Canada will be able to develop a vaccine and will be able to manufacture one and from a Canadian perspective that’s really good because we wouldn’t want to be relying on other countries,” he said. “Because I wouldn’t be surprised if other countries basically nationalized any supply their companies made.” “Would you put it past Trump to say all the doses are going to stay in the U.S., we’re not going to send any out anywhere else?” he asked. Nickerson says Canadian policy-makers should not rely on the good faith of the pharmaceutical industry.