Responding to Cholera as COVID-19 threatens Kenya’s health system

Heavy rains across Kenya and the wider region have led to floods and forced many people from their homes. Now, the town of Telesgaye, a community in Kenya’s north-east Marsabit County, is fighting a cholera outbreak.

The first cases of cholera were reported in Silicho, an Ethiopian village near the border with Kenya, six kilometres north of Telesgaye, in December 2019. Since then, the outbreak has led to thousands of patients needing treatment; a situation that could prevent an effective response on the Kenyan side if cross-border measures to curtail the spread of the disease are not strengthened.

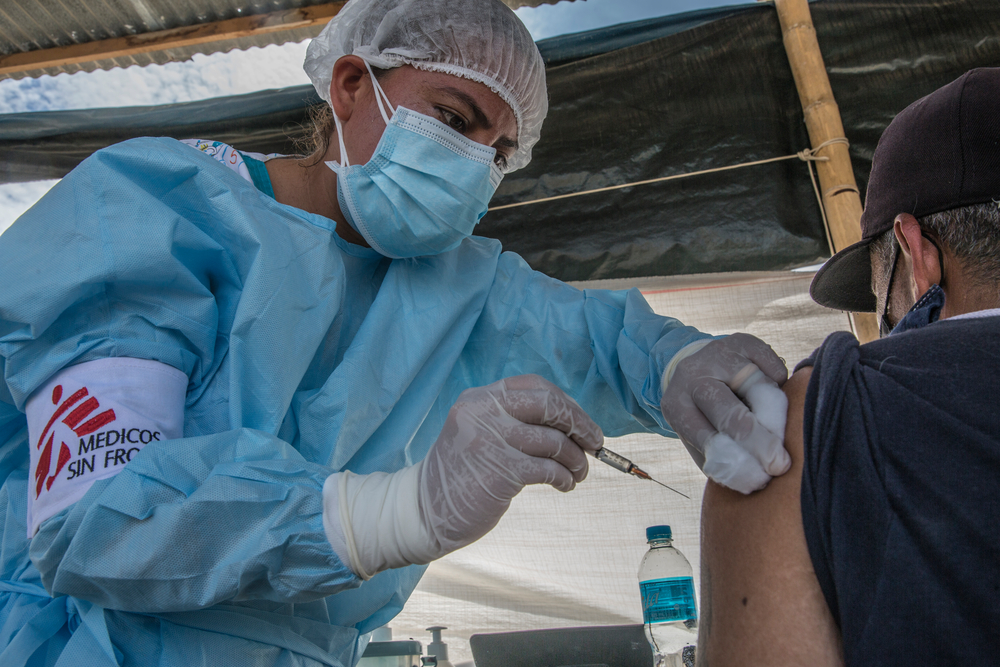

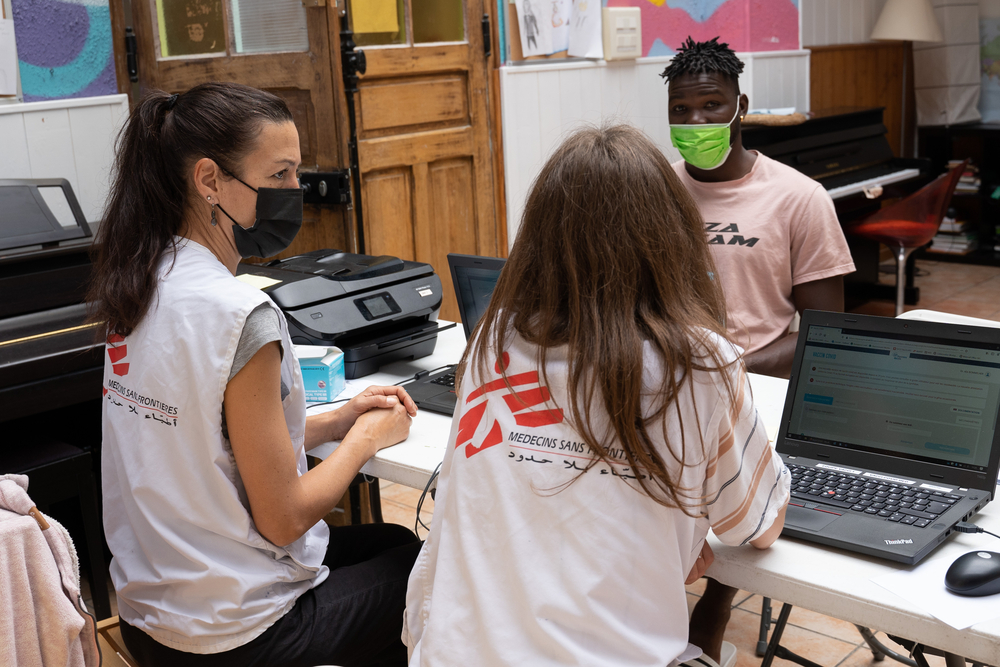

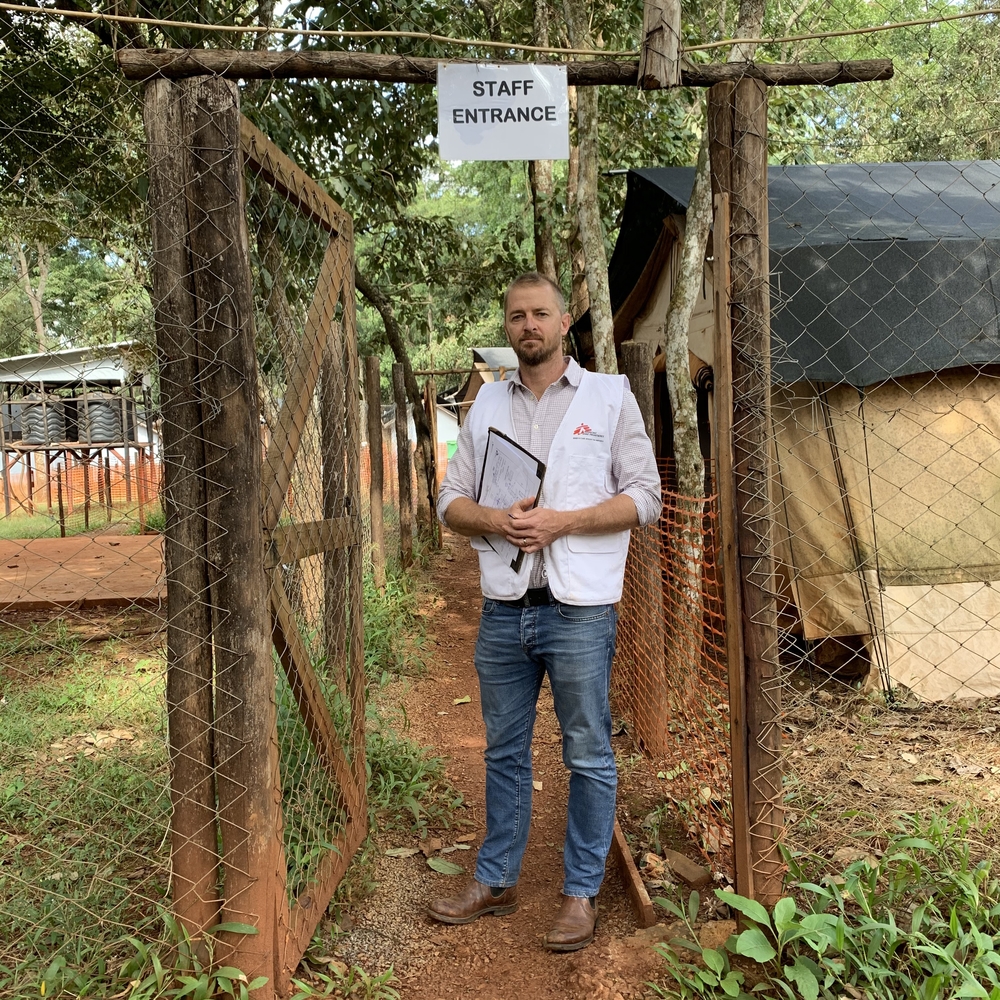

“People are crossing the border every day and this can’t be stopped. Having cross-border surveillance will help public health authorities respond to the cholera outbreak in an efficient manner,” says Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) head of mission, Edi Ferdinand Atte.

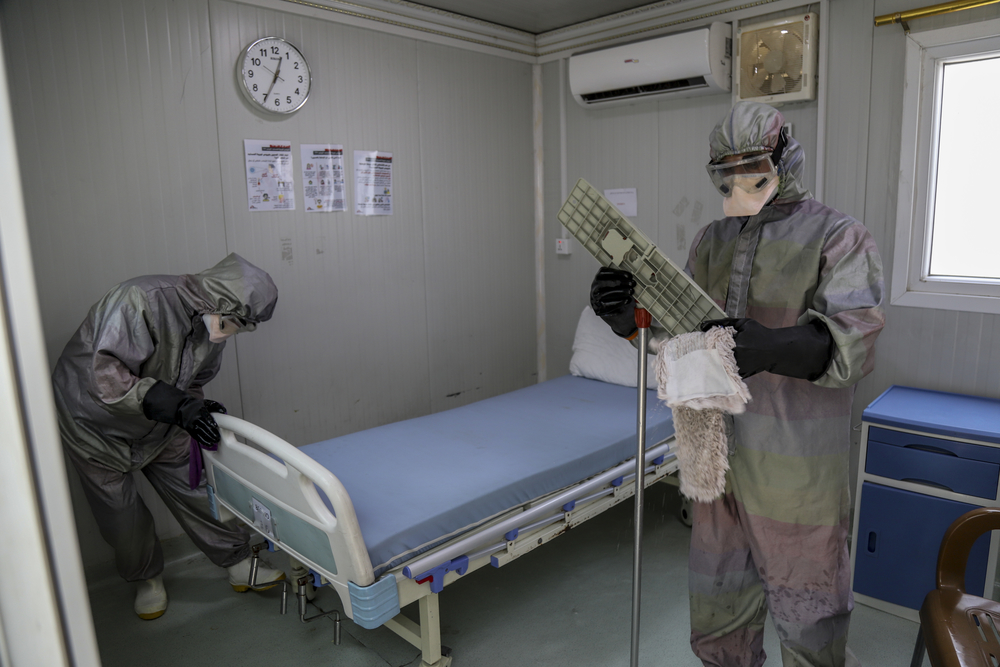

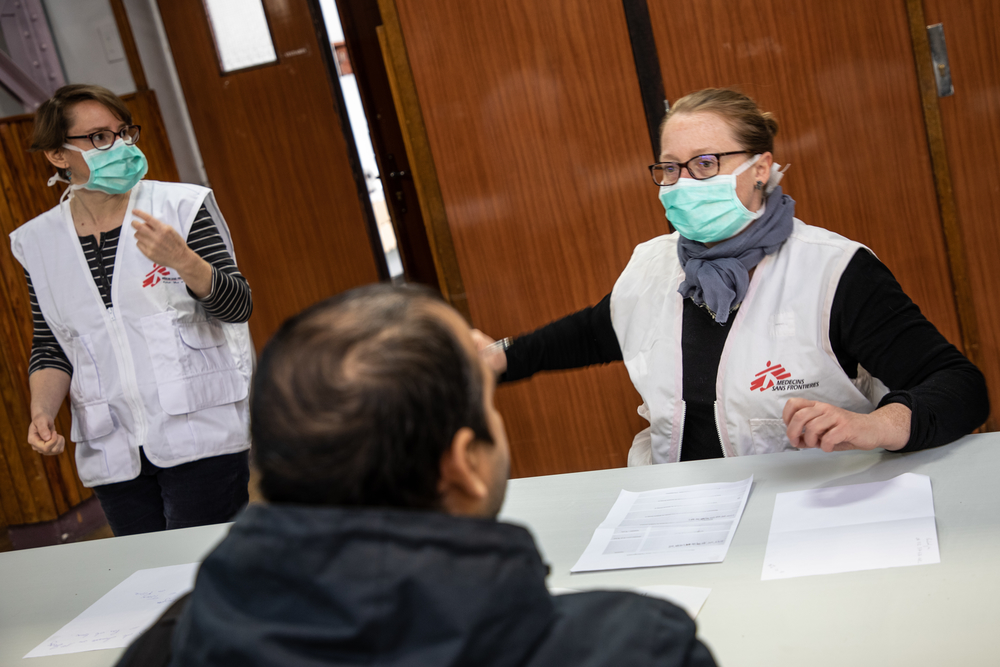

Aigur walked for about an hour from Watali to Telesgaye with her eight-year-old son Naftal on her back to bring him to the cholera treatment unit set up by MSF. For several hours, he had acute diarrhea and vomiting, and needed urgent medical care. Since early May, MSF has supported county health authorities at the Telesgaye health centre, setting up a 10-bed cholera treatment unit and adding an additional six beds to complement the existing four in the Illeret health unit, 10 kilometres from Telesgaye. Since the outbreak was declared, 274 cases were registered. As of May 17, when the team left Illeret back to Nairobi, numbers having dwindled, MSF had admitted and treated 39 people; 31 in severe condition.

“One patient stands out for me,” says MSF nurse Pacific Oriato. “She was brought to the cholera treatment unit and later discharged thinking all was well. The following day, she was rushed back in and, while doing my morning patient examination round, I found her in a critical condition. After successful treatment, she was discharged, but then her younger brother was brought in by their father in an even worse condition than her. The two children both tested positive for cholera. It breaks my heart to see the devastation knowing how treatable this disease is.”

Covering almost 71,000 km, Marsabit County is Kenya’s largest county. It straddles the Chalbi desert – the only one in East Africa – along the border with Ethiopia,and is extremely remote and isolated. The livelihoods of over 300,000 people in this arid and semi-arid region rely mainly on rearing animals and growing crops intermittently based on the weather patterns. Many Marsabit communities have already felt the impacts of climate change on their food security as persistent droughts and intercommunal clashes persist.

“In recent years, the county has gone for almost a year without rain. Communities have been forced to fetch water by digging along Lake Turkana’s tributaries banks, which are also used for defecation by community members and their animals. As a result, the likelihood of consuming contaminated water is high. As a nomadic population constantly on the move due to cattle, food raiding violence and water scarcity for themselves and their herds of cattle, building latrines is not a priority, and such living conditions mean a high risk of exposure to water-borne diseases like cholera,” says Ibrahil El Lahham, MSF water and sanitation expert.

The cholera outbreak comes at a time when there are already more than 700 cases of COVID-19 across Kenya, with one patient reported in Wajir County, next door to Marsabit County. Movement, for trade or other purposes, between the counties, is high.

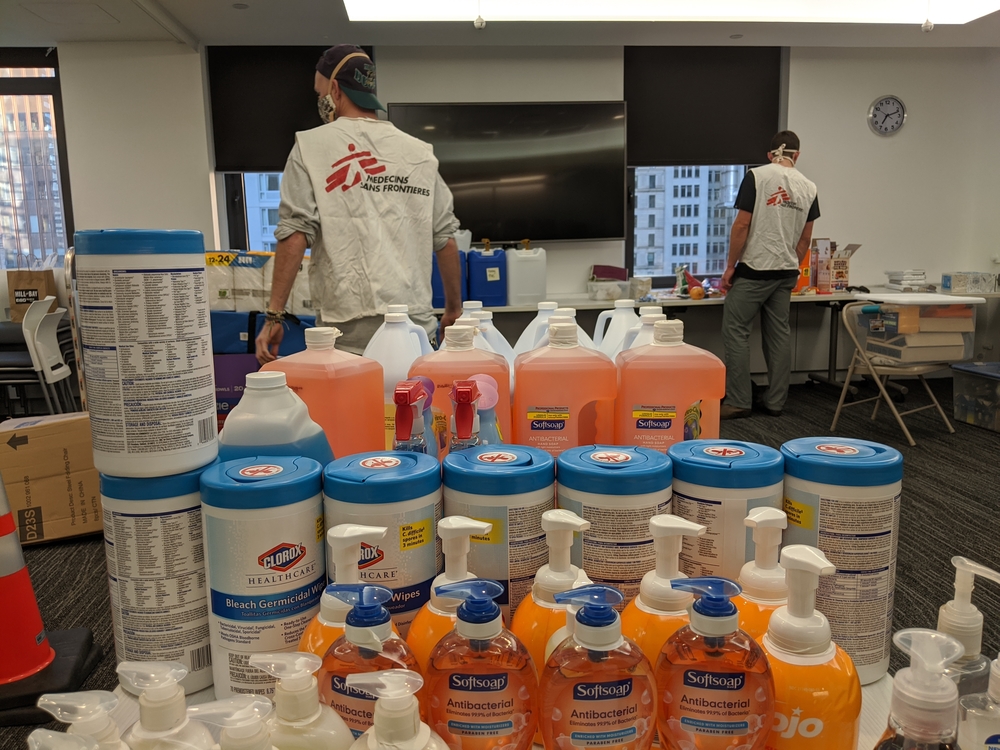

“The county’s fragile health structure, limited skilled personnel and lack of protective gear means that treating other illnesses alongside cholera could leave a devastating mark on communities experiencing an outbreak,” notes MSF Kenya head of mission, Edi Ferdinand Atte.