COVID-19: What is MSF doing?

The Covid-19 epidemic has already spread to more than 100 countries around the world. These include countries whose health systems are fragile and where Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) teams have a long-standing presence, as well as regions such as Europe, where the capacities are more robust but where the epidemic is particularly virulent. Travel restrictions generated by the outbreak also directly affect MSF’s work around the world.

What questions does MSF face in this context? An interview with Clair Mills, MSF’s medical director.

Are we right to be afraid of Covid-19?

Several factors make this virus particularly worrying. Being a new virus, there is no acquired immunity; as many as 35 candidate vaccines are currently in the study phase, but experts agree that no widely usable vaccine will be available for at least 12 to 18 months. The case-fatality rate, which by definition is calculated only on the basis of identified patients and is therefore difficult to estimate accurately currently, appears to be around 1%. It is known that at least some of those affected can transmit the disease before developing symptoms – or even in the absence of any symptoms. In addition, a very high proportion – around 80% – of people develop very mild forms of the disease, which makes it difficult to identify and isolate cases quickly. Confirmation of the diagnosis requires laboratory and/or medical imaging capabilities that are only available in reference structures. It is therefore not surprising that it has proved impossible to contain the spread of the virus, which is now present in more than 100 countries around the world. This epidemic is therefore very different from those – such as measles, cholera, or Ebola – in which MSF has developed its expertise over the last few decades.

Furthermore, it is estimated today that approximately 15-20% of patients with Covid-19 require hospitalization and 6% require intensive care for a duration of between 3 and 6 weeks. This can, of course, quickly saturate the healthcare system. This was the case in China at the beginning of the epidemic, and is currently the case in Italy. There are currently more than 1,100 patients in intensive care units in the country and the hospital system in the North which has been overwhelmed by the rapid increase in the number of patients.

As is often the case during this type of epidemic, medical staff members themselves are particularly exposed to infection. Between mid-January and mid-February in China more than 2,000 health care workers were infected with the coronavirus (3.7% of all patients).

This epidemic is likely to lead to the disruption of basic medical services and emergency facilities, the de-prioritization of treatment for other life-threatening diseases and conditions and for other chronic infectious diseases everywhere but especially in some developing countries, where the health system is already fragile.

Some feel that the response to this epidemic is overreacting, and that the remedies – border closures, quarantine, etc – are likely to be worse than the disease. Is this justified?

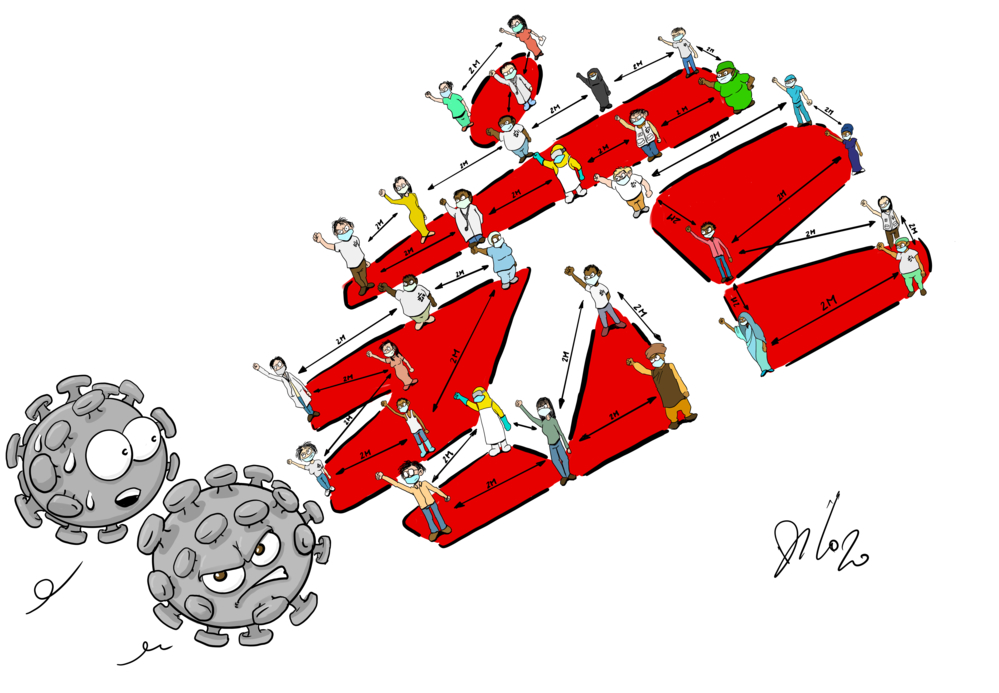

Even though they cannot prevent the outbreak from spreading the measures currently being taken by many countries can slow it down by reducing the increase in cases and limiting the number of severe patients that health systems have to manage at the same time. The aim is not only to reduce the number of cases but also to spread them over time, avoiding congestion in emergency and intensive care units.

What are MSF’s priorities in this context, and its main concerns?

Priorities for intervention vary from one context to another.

In some areas that seem to be spared today, such as the Central African Republic, South Sudan and Yemen, where fragile or war-torn health systems are already struggling to meet the health needs of the population, it is necessary to protect healthcare personnel and to limit the risks of spreading the epidemic as much as possible. This is done by implementing prevention programs:

- identifying areas or populations at risk

- running health awareness and information activities

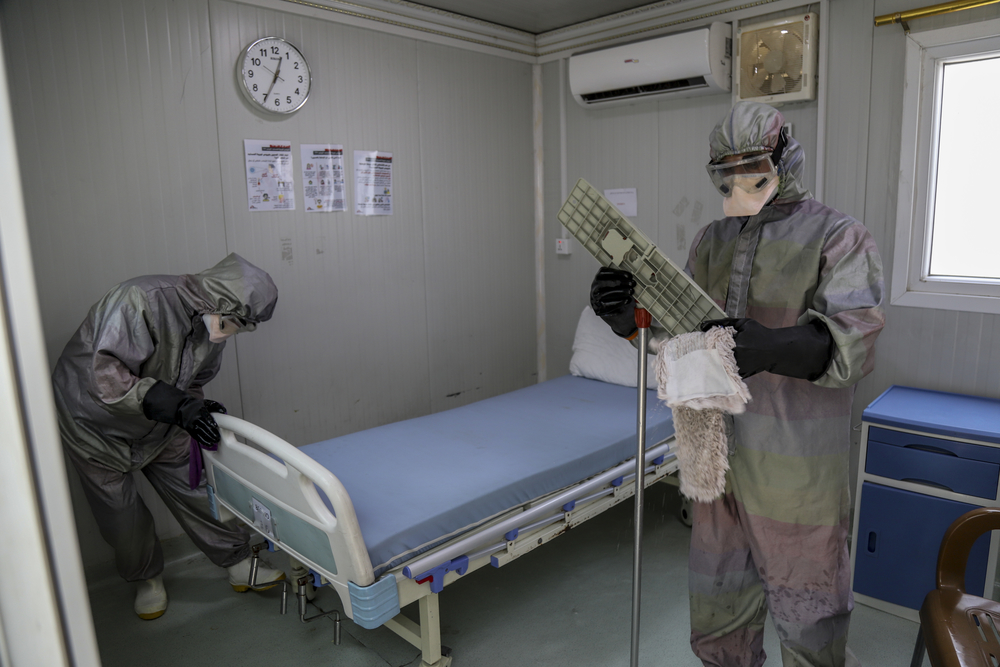

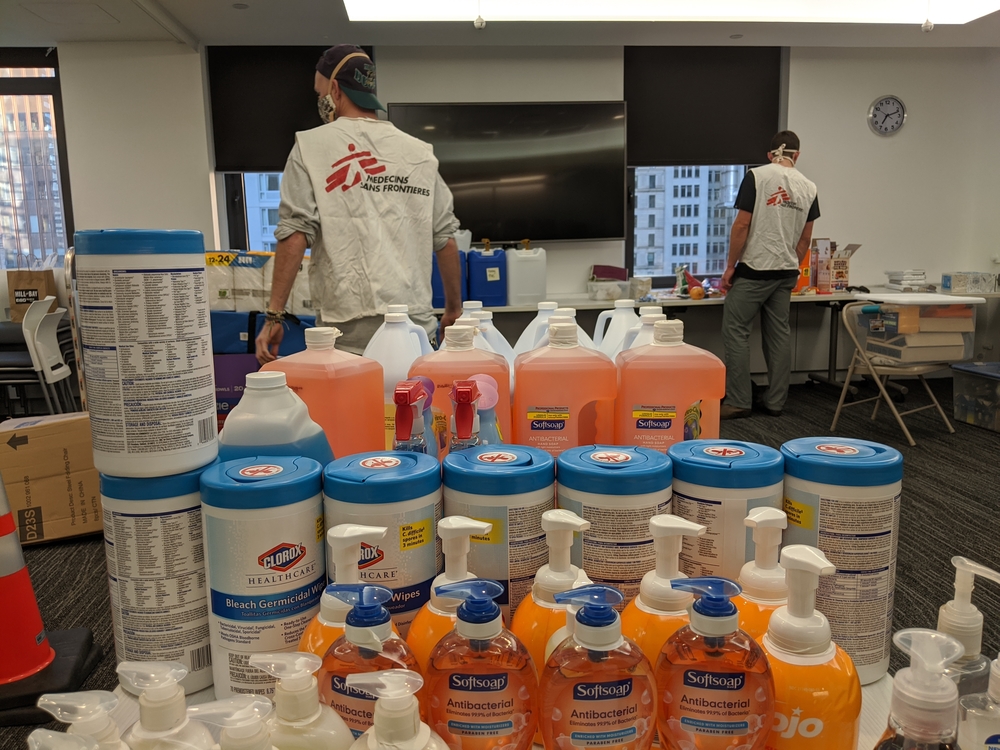

- distributing soap and protective equipment for healthcare personnel

- reinforcing hygiene measures in medical structures – to prevent our hospitals and clinics from becoming places where the disease is transmitted.

In these countries where MSF has a longstanding presence we want to contribute to these efforts against Covid-19 while ensuring continuity of care against malaria, measles, respiratory infections, etc.

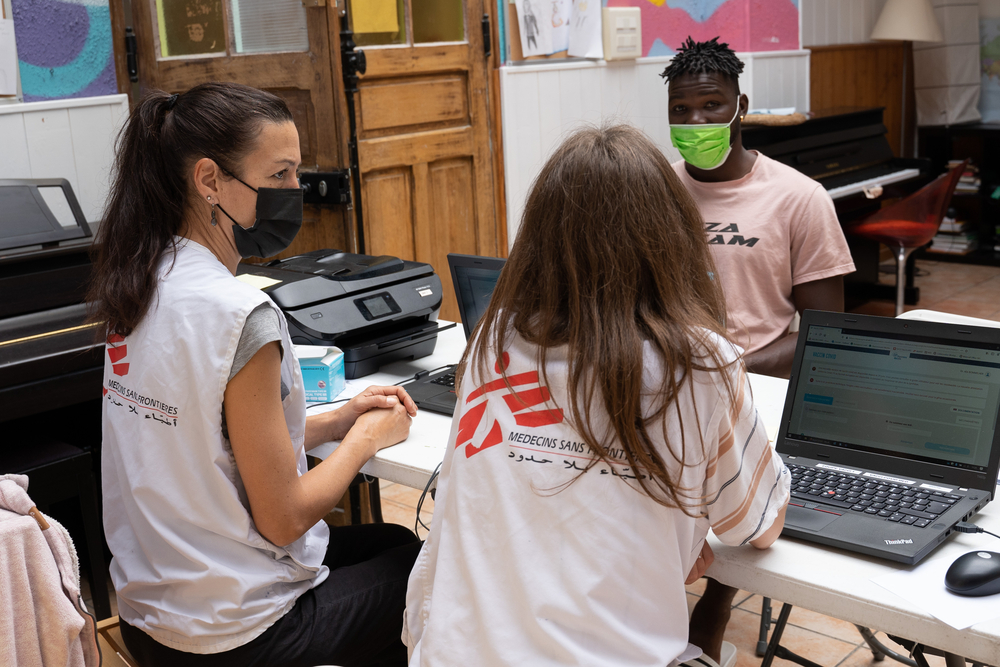

This continuity is now weakened by the restrictions (a ban on entering the country, preventive isolation for 14 days, etc.) imposed by governments on staff from certain countries, such as Italy, France and Japan, where some of our international staff come from, as well as the closure of borders and the suspension of certain air links. Despite these constraints, our strength lies in the fact that we can rely on locally recruited staff in our countries of intervention. They represent 90% of our employees in the field.

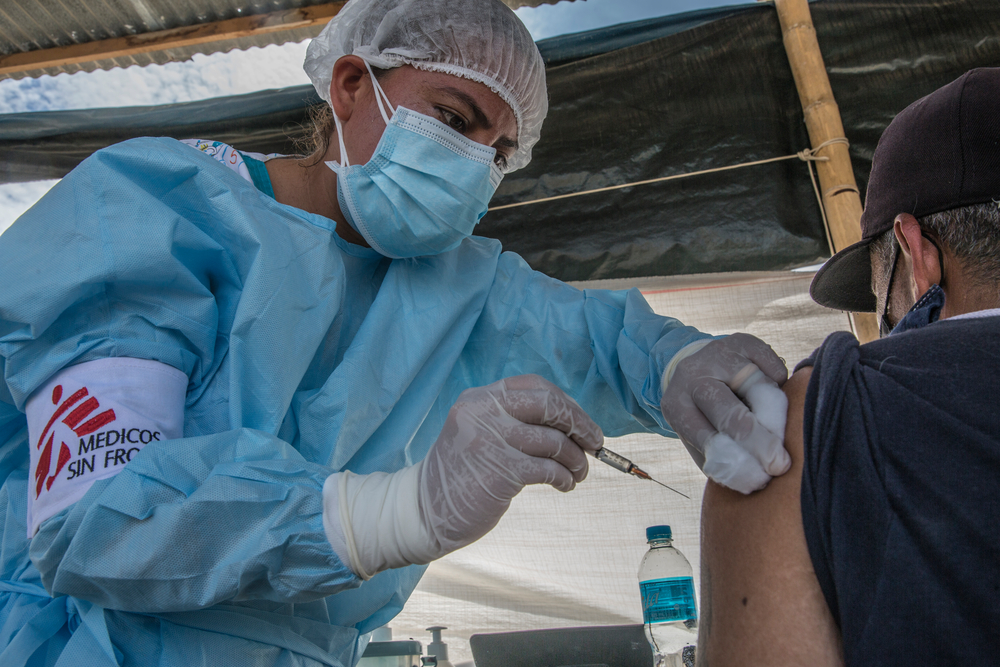

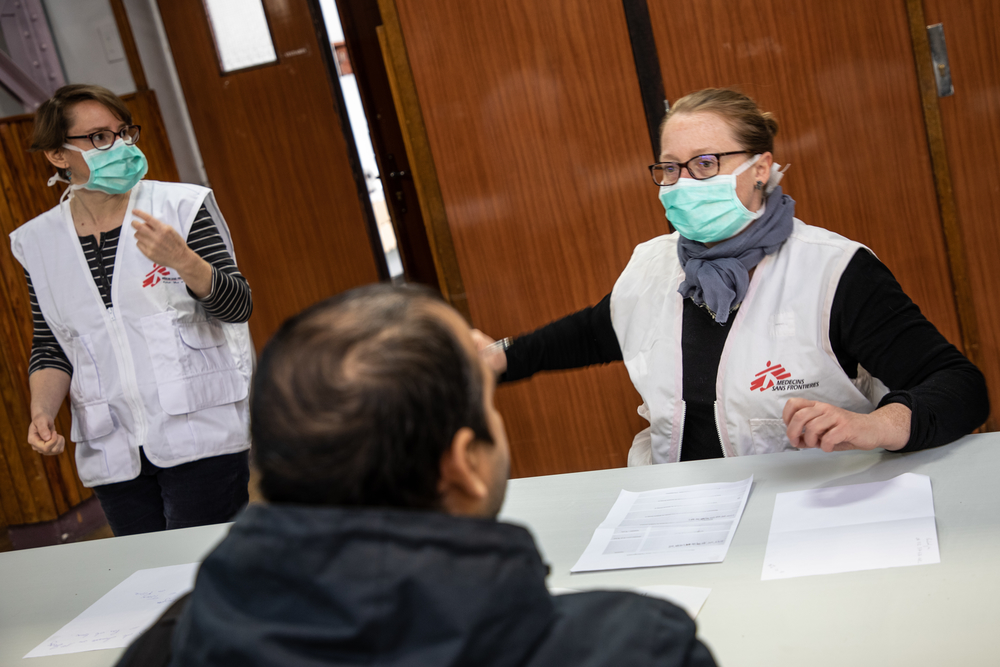

In countries where health systems are more robust but where the epidemic is particularly active, such as Italy or Iran, the main challenge is to avoid overloading hospital care capacities. In these contexts we can contribute to the efforts of national medical teams by making MSF staff available to support or relieve them when needed. We can also help by sharing our experiences in triage and control procedures for infections acquired during epidemics. We have provided teams to support four hospitals in northern Italy and have also offered support to the Iranian authorities to support them in caring for severe patients. Depending on the evolution of the epidemic in France, we will make available to the response our experience, our logistics and the know-how of our staff, if they can be useful.

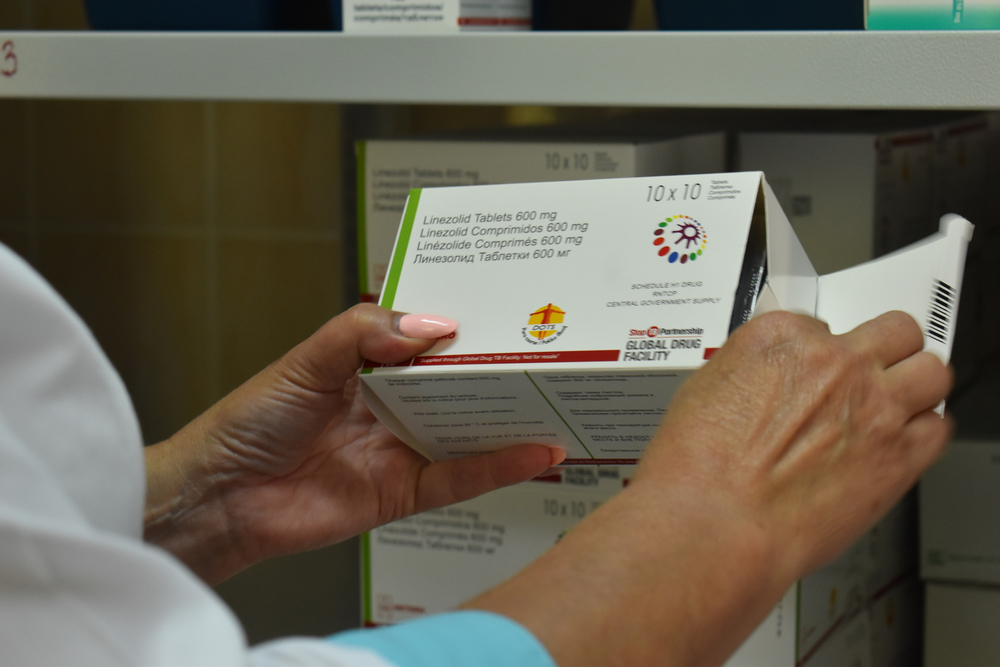

One of the keys of the fight against Covid-19 is the availability of protective equipment, in particular masks and gloves used for medical examinations. The anticipation of shortages leads to requisitions by many states, which can in turn become a reflex on the part of states to monopolise these precious resources. In the current context such equipment should on the contrary be considered as a common good to be used rationally and appropriately and therefore to be allocated as a priority to health workers exposed to the virus, wherever they are in the world.

Generally speaking, this pandemic requires solidarity not only between states but at all levels, based on mutual aid, cooperation, transparency, the sharing of resources, and, in the affected areas, towards the most vulnerable populations and towards caregivers.