In remote Kyrgyzstan, COVID-19 puts strain on health system

As COVID-19 cases surge in Kyrgyzstan, especially in the capital Bishkek, rural and remote regions are bracing themselves for the virus by scaling up preventive measures while simultaneously striving to guarantee essential medical care, especially for women and children.

Despite the country’s strong health system, maintaining quality services outside big cities has suffered in recent years as a consequence of weakening investment in the sector. The country also has a high incidence of chronic diseases and an exceptionally high percentage of people with chronic ailments who require long-term care.

In Kadamjay, a stunning but harsh region of southwestern Kyrgyzstan, accessing healthcare is challenging, even without the threat of COVID-19, as the long distances can make it difficult for people to reach health centres. Medications for children under five and pregnant women are free in Kyrgyzstan, but most people have to dig into their own pockets for medicines, as only a few are covered by health insurance. With limited opportunities to earn a living and low incomes, many people simply cannot afford to get the treatment they need.

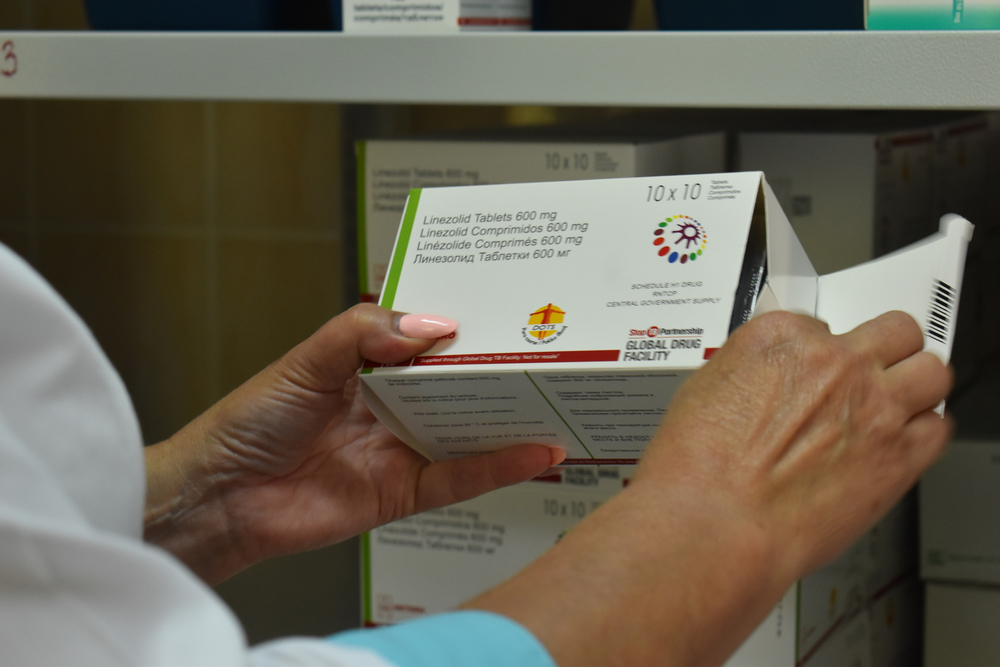

For the past four years, Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) has been providing medical assistance in Kadamjay, where rates of some chronic diseases are among the highest in Kyrgyzstan. Working closely with the Ministry of Health, our teams support district health authorities in the screening, diagnosis and prevention of ailments including diabetes, hypertension and anaemia, which is particularly widespread among children.

To improve screening and diagnosis for a range of chronic diseases, investment in laboratory capacity has been necessary. Our teams have renovated and repaired existing medical equipment and have trained Ministry of Health staff in the practical use of diagnostic equipment such as ultrasounds and cold coagulators, as well as in adhering to standard treatment guidelines.

More recently, MSF has also been working closely with health authorities to reinforce healthcare for women and children, with an emphasis on sexual and reproductive health, including antenatal and postnatal care.

Sustaining healthcare amid a looming COVID-19 threat

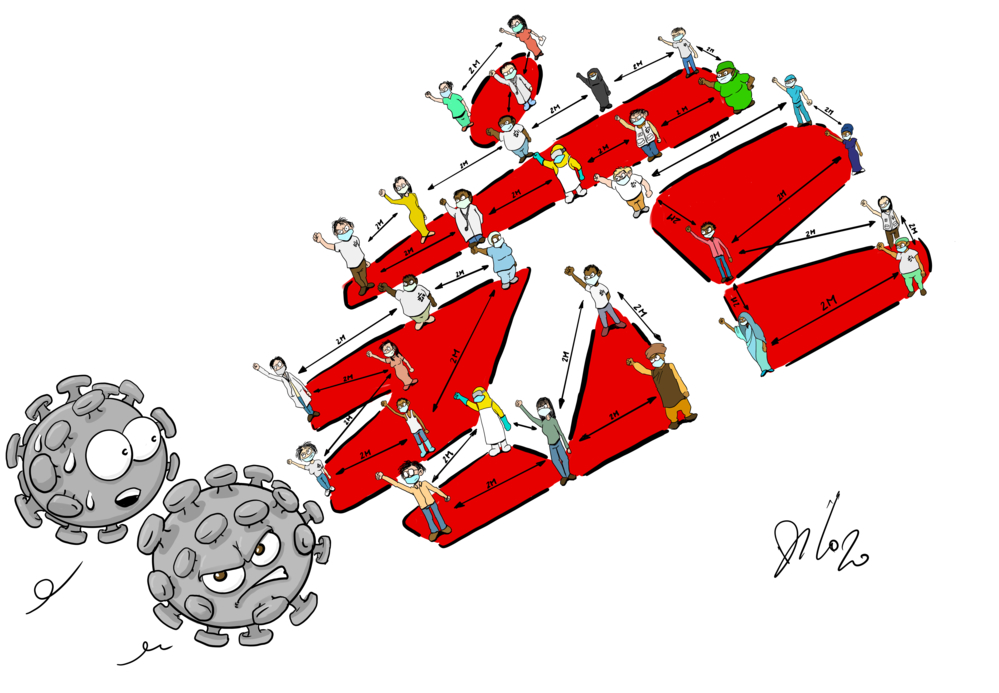

In recent days, the number of people diagnosed with COVID-19 has risen steeply. So far, over 29,000 people have contracted the virus in the country. Kadamjay region may have been spared the worst of COVID-19 for now, but the looming threat of the virus has prompted our teams to adapt existing medical services and put in place measures to prevent the disease spreading through the community.

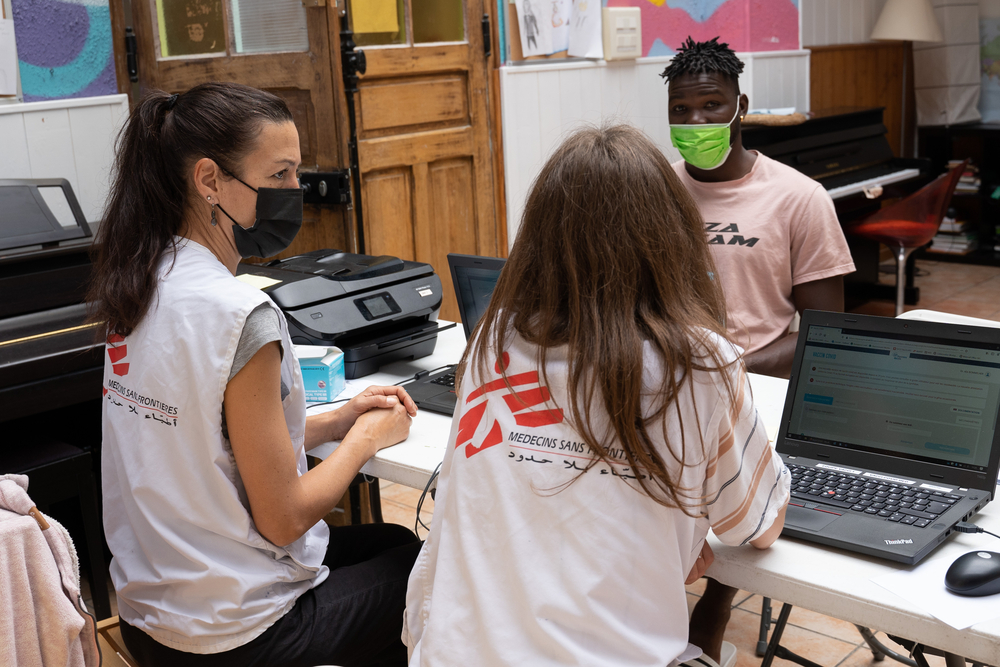

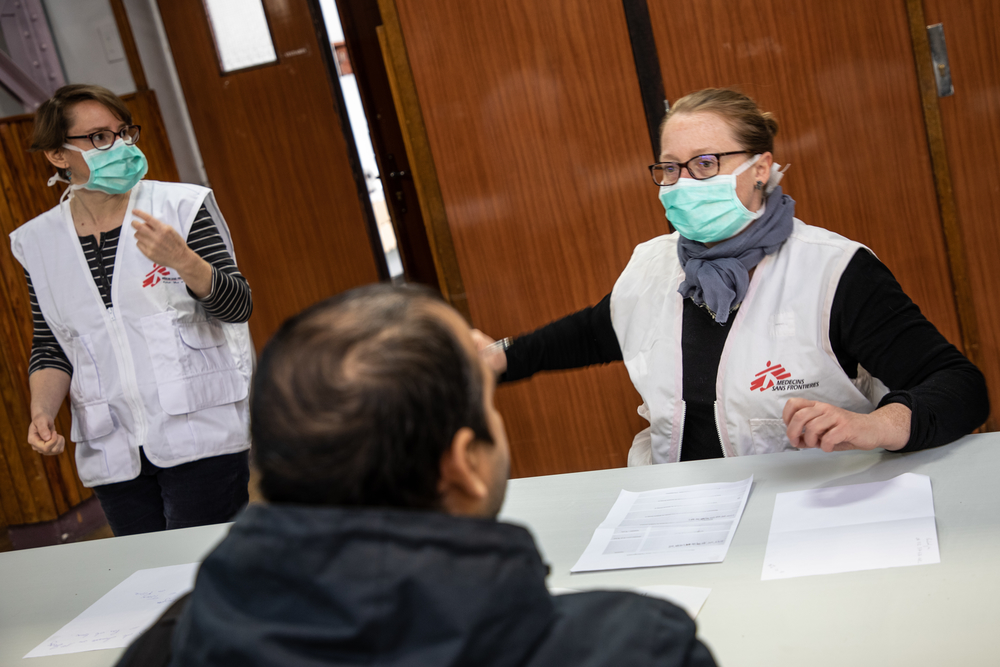

MSF teams were already carrying out home visits for some consultations, working with the region’s health authorities. But since the start of the coronavirus pandemic, home visits and remote consultations via WhatsApp have become the norm.

“In order to avoid a high concentration of people in health centres, we have increased home visits for children and for postnatal care, especially for patients with non-communicable diseases, who are at high risk of COVID complications,” says Kevin Coppock, MSF’s country director in Kyrgyzstan. “For other routine consultations, including antenatal care, we organise WhatsApp video calls with patients.”

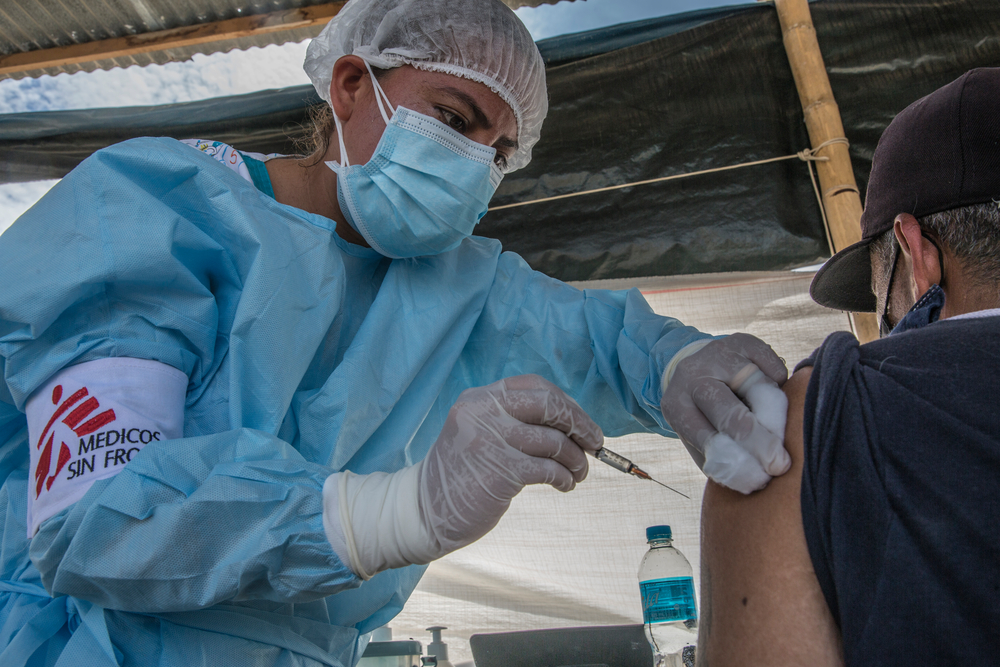

MSF teams are currently assisting the region’s health authorities in reinforcing COVID-19 preparedness in this largely rural area, offering technical advice, providing logistics assistance, supporting health promotion initiatives and assisting in epidemiological surveillance through data collection.

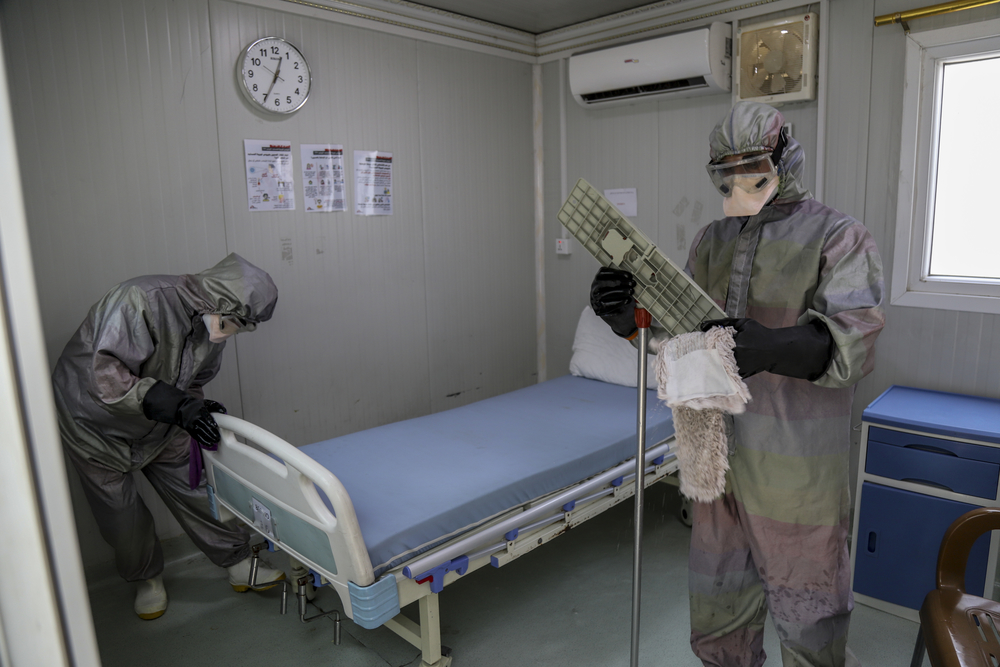

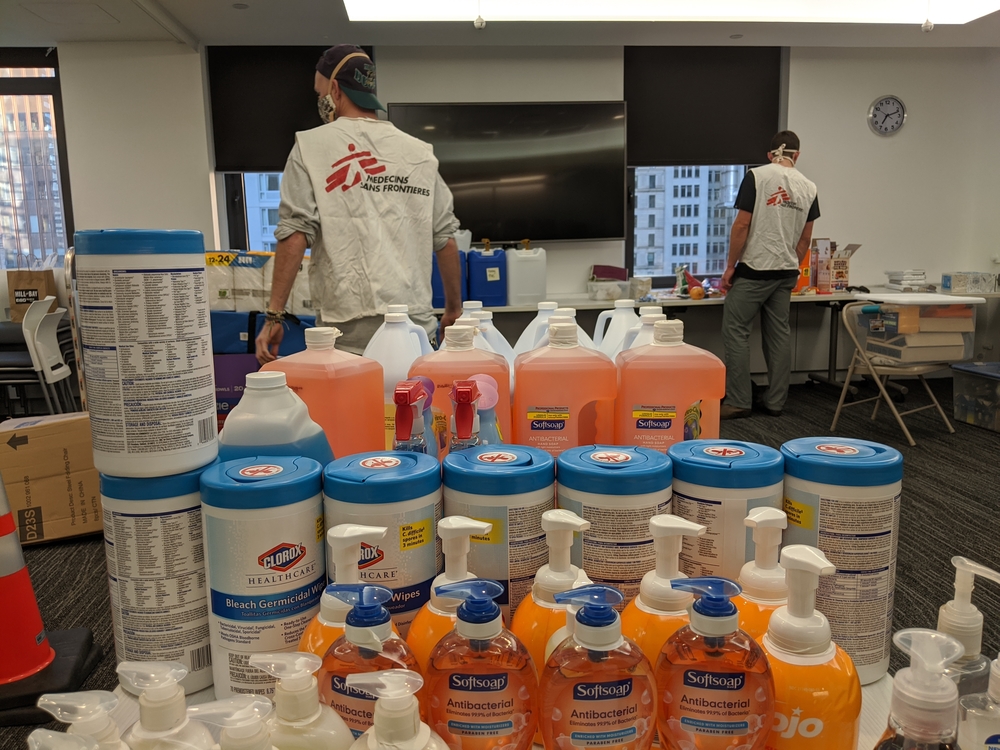

MSF is also working to infection-proof four of Kadamjay’s main hospitals, providing advice and training on infection prevention and control, and providing disinfectants and personal protective equipment for health staff. MSF has also distributed more than 4,500 masks to protect patients with non-communicable diseases and other medical complications.

While most of MSF’s essential health services have been able to continue, others have had to be put on hold to avoid spreading infection. “As Kadamjay district has a high number of patients with chronic diseases, we are being extremely cautious in not exposing people to unnecessary risks,” says Coppock. Cervical cancer screening is one of the services to be put on hold.

Cervical cancer is a leading cause of death for women in Kyrgyzstan, but prevention and screening options are limited. In Aydarken, MSF introduced cervical cancer screening and prevention, including the treatment of cervical lesions, with the aim that health authorities would scale it up across the country. But this will have to wait. “We continue to follow how the virus evolves, with the intention of restarting activities as soon as the situation allows,” says Coppock.

At the same time, high infection rates among health workers in COVID-19 hotspots in the country is a matter of further concern. “Even before the pandemic, there weren’t enough medical workers, especially in remote areas of our country”, says Isamedin, an epidemiologist with MSF. “If some of them were to fall sick, there would be no one to replace them”.

With COVID-19 preparations using up enormous resources, people’s barriers to accessing quality healthcare risk being further entrenched. And for many families in this region, especially those who depend on the salary of a migrant worker, the economic toll could further impede access to healthcare as remittances dry up.

“COVID-19 should really serve as a wake-up call to reduce health inequities between and within countries,” says Coppock.